‘No. But she may guess now that I have seen the locket and reacted as I did,’ Thomas admitted.

‘And if she knows then it is possible that others will learn the truth. If it is discovered that I am a spy, my life is forfeit.’

Thomas thought for a moment. ‘Maria will not put your life at risk. She has kept the locket a secret. Even from Oliver. ’

‘Sir Oliver Stokely?’

Thomas smiled sadly. ‘Her husband, as it turns out.’

‘But he’s a member of the Order. Marriage is forbidden.’

‘So are many things but what is not flaunted is overlooked.’ Richard gave him a curious look. ‘It must pain you to have discovered this.’

‘As much as it did to discover I had a son. A son I would have been proud of.’

Richard looked away quickly. ‘If Sir Oliver discovers the truth then I will be arrested, tortured and executed. Even if he does not have the stomach for it, La Valette will insist on it. I would rather die on St Elmo with a sword in my hand than on the rack or at the end of a rope. I shall come with you.’

‘No.’ This time Thomas did reach out with his hand and clasped that of his son. ‘It is certain death. I will not send you to such a fate.’

‘You do not send me. I choose to come.’

‘And I tell you to stay.’ The words came out quickly, like an order, and Thomas regretted his tone at once. He lowered his voice and continued more gently. ‘Richard . . . my son, I beg you, do not come with me. This is a fate I have chosen for myself. I can bear it if I know that it gives you, and Maria, a chance to survive the siege. If you were there with me, I would only fear for you. If you were to be harmed before my eyes, I would die a thousand deaths in St

Elmo, not just one. Please.’ He squeezed Richard’s hand. ‘Stay here.’

Richard was silent for a moment, deep in thought, then he nodded reluctantly and Thomas eased himself back with a sigh of relief. ‘Thank you.’ He withdrew his hand and stroked his brow. ‘There is one thing I would know before I leave. This document that you were sent to find. What is it?’

Richard looked at him with a slight air of suspicion. ‘Why do you ask?’

‘If I am to die then I would do so with a mind unclouded by doubts. Before I left London, Walsingham assured me that he needed the document in order to save many lives in England. He could have been lying to me. I would like to know if I was sent here On a dishonest pretext, or if I have done something for the good in this world. So, my son, tell me. What is so important that powerful men in England conspired for years so that we two might be brought to this place?’

Richard considered the request briefly, and nodded. ‘I already know the contents of the document, assuming that Walsingham was telling me the truth.’ He smiled. ‘My trust in his word is no longer quite what it was. You had better read the document for yourself. Be good enough to stand up.’

Thomas did as he was told and Richard lifted the end of the cot and swung it away from the wall. The surface had been plastered long ago, but the boisterous activities of generations of squires had cracked the plaster in many places and bare bricks were exposed. Richard knelt beside a section of the wall that he had exposed and drew his dagger. He eased the point between two of the bricks and carefully worked one out far enough to get a grip on it and extract it. He placed the brick on the floor and reached his hand into the dark opening.

His expression froze, and he stretched his fingers as far into the hole as possible before he cursed under his breath.

‘What’s the matter?’ asked Thomas.

‘It’s not there.’ Richard looked round with a shocked expression. ‘It’s gone.’

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR

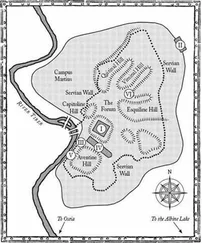

Ten days later, 22 June, Fort St Elmo

The enemy guns fell silent and for a moment there was silence across the scarred ground .at the end of the Sciberras peninsula. The dust billowed slowly about the fort and settled on the bodies sprawled on the ground, making them look like stone sculptures. Some had lain in the open for many days and were bloated and corrupt with decay, the sickly sweet stench filling the air. It was mid-June and the heat of the day would soon begin to add to the discomfort, and bring the swarms of insects that settled to gorge themselves on the wounds and viscera of the dead and dying.

For the defenders, each day was torment as the sun beat down on them while they squatted behind the parapet, enclosed in padded jackets and armour that quickly became too hot to touch and as much a source of torture as protection from harm. Sweat streamed freely down their cheeks and dripped from their brows as they awaited the enemy. For some men, older or weaker than their comrades, the heat was too much and they collapsed, gasping for air as they tore at the buckles of their breastplates in an effort to remove their armour. Some died as their hearts gave out, gurgling incoherently while their swollen tongues writhed against cracked lips.

There was a sudden movement from the Turkish trenches and then a green banner rippled upright and drums and cymbals crashed out, accompanied by a throaty cheer. Heads appeared above the top of the trench and a moment later the first of the enemy swarmed into view.

‘Here they come!’ Captain Miranda yelled from the keep. He turned to the drummer standing ready beside him. ‘Sound the alarm!’

The shrill rattle of the drum rang out across the crumbling walls of the fort. The men who had been sheltering inside the fort spilled out into the courtyard and raced up the steps to their stations on the walls to join their comrades on sentry duty. At once the two cannon and snipers waiting on top of the captured ravelin opened fire, striking down several men as they reached the top of the stairs.

Thomas was behind the barricade erected beyond the rubble slope that was all that remained of the north-west comer of the fort. And Richard was with him, for nothing would persuade him to stay in Birgu after he discovered that the document was missing. They had been called to the wall an hour before dawn when the first prayers of the imams had been heard by the sentries — a sure sign of a pending attack. Thomas looked round as the Spanish soldiers assigned to his position crouched down below the level of the parapet and bent double as they ran to their places. Along the barricade stood tubs of water big enough for a man to leap in and extinguish the fire of enemy incendiary weapons. There were also small piles of arquebuses, loaded and ready to fire, and the defenders’ own stock of incendiary weapons — small clay pots filled with clinging naphtha, from which fuses protruded, ready to be lit before the pots were hurled amid the enemy. To each side of the barricade, where the parapet still stood and overlooked the ditches, other men readied the first of the fire hoops, and fanned the small braziers into flame in readiness to set light to them. Thomas and Richard squatted behind the centre of the barricade, beside the naphtha thrower and its two-man crew. One stood ready to operate the bellows while the other connected the leather hose to the keg containing the mixture that would burn with hellish ferocity once it was ignited by the flaming wick in front of the nozzle of the bellows.

‘Careful with that,’ said Richard. ‘Unless you want us to go up like a torch.’

‘I know what I’m doing, sir,’ the Spaniard replied with a grim smile. ‘Just keep out of my path, eh?’

The cheers of the enemy grew louder as they reached the edge of the ditch and started to scramble over the rubble that now filled it.

‘Stay down!’ Thomas shouted, waving back the handful of his men who had started to nervously glance over the edge of the barricade. The Turkish snipers kept up their fire until the last possible moment and, as if to justify Thomas’s warning, a ball ricocheted off a block of stone and clanged off the fan crest of a morion helmet a short distance to Thomas’s left. The man dropped back, dazed and blinking.

Читать дальше