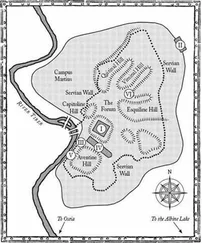

Meanwhile St Elmo was fully provisioned and the modest cistern that lay beneath the keep was filled to the brim. Gunpowder and shot was placed in the storerooms, ready to feed the small complement of artillery that was mounted on the fort’s gun platforms. Stout boxes filled with shot for the arquebusiers were positioned along the parapet and hessian sacks were filled with soil and piled in the courtyard, ready to fill any breaches in the walls.

Each day ships entered the harbour with cargoes of grain, wine, cheeses and salted meats. There were also tools and building materials needed to prepare the defences and ensure that damage could be repaired. Some of the vessels had been intercepted at sea by Captain Romegas and his galleys and summarily requisitioned since the Order’s needs overrode any notions of legality. The owners and crews were promised compensation in due course, though that depended upon Malta surviving the Turkish onslaught.

In the first days of spring the companies of Spanish and Italian mercenaries hired by the Grand Master began to arrive and were assigned billets in the towns of Birgu and Mdina. They were hardened professionals and had been lured by generous payments from the Order’s coffers, and the prospect of loot. It was well known that the Sultan’s elite corps, the Janissaries, were richly dressed and paid handsomely in gold and silver. Their corpses would provide rich pickings for the mercenaries. There were also small groups of adventurers who travelled to Malta to offer their services to the Order, motivated by religious fervour and the desire for glory. Amid the new arrivals were a handful of knights who had received and honoured the request to return to Malta and fight alongside their brothers.

Throughout April the defenders laboured hard to raise the height and depth of the walls and bastions that protected the promontories of Senglea and Birgu. In front of the wall, slaves and Maltese work gangs swung picks to break up the rocky ground and excavate a defensive ditch deep enough to hamper attempts to scale the walls. So short was the time and so desperate the need to bolster the defences that none was spared the duty of toil. The Grand Master, despite his advanced years, appeared every morning in a plain tunic and a strip of dark cloth tied about his brow, ready to work for two hours, breaking ground with a pick or joining the long chain of workers carrying baskets of rubble inside the walls of Birgu. All the knights and soldiers were required to do the same and the grudging indifference of the local people gave way to surprise and then respect as they found the sons of Europe’s noblest families working alongside them. Within days they had taken to cheering La Valette when he appeared each morning and took up his pick or basket.

Buildings close to the walls that might be used by the enemy for shelter were demolished and the timbers and rubble taken into Birgu to add to the material set aside for repairs. Those made homeless by the destruction of their houses were given billets in the town. There was little problem accommodating them as a steady stream of the town’s inhabitants with sufficient wealth to fund their temporary exile took ship for Sicily, Italy and Spain, there to await news of Malta’s fate.

As April drew to an end all knew that the Turkish fleet would already be at sea, heading west. Orders were given for the farmers and villagers across the island to prepare to abandon their homes and seek shelter in Mdina, a fortified hill town that had once been the capital of the island, or within the walls of Birgu. No crops, cattle, goats, grain or fruit was to be left for the enemy to forage and preparations were made to foul the wells and cisterns with rotting animal carcasses and slurry. The Turks would find a wasteland waiting for them when they landed and would be forced to ship in their sustenance, or starve before the lines of the Christian defences.

At first Thomas, Richard and Sir Martin had been assigned to training the Maltese militiamen in the most basic of fighting skills. It had long been the policy of the Order to discourage the islanders from using weapons out of fear that the local people might be emboldened to rebel against the Order of knights that had been imposed on them. As a result the majority of them were strangers to swords, pikes and arquebuses and only a handful had ever worn any armour. There were some who had been selected to serve as soldiers of the Order and these assisted with the training and translated the commands into the local tongue that sounded more like Arabic than any European language to an unfamiliar ear. Indeed, the islanders, with their dark features and skin, looked more like Moors and Turks than Christians. Yet they were fanatic in their loyalty to the Church of Rome and hatred of the enemy who been preying on the Maltese for over a hundred years. They were keen to learn and were soon handling their weapons like experienced soldiers. Thomas had insisted that they should also be taught to use the arquebus, but such was the shortage of gunpowder that only three live firings were permitted once the militiamen had learned how to load the weapons.

Once the hurried training was complete, the English knights and their squires were allocated to the work party under Colonel Mas, one of the mercenaries recruited by the Grand Master. They were tasked with constructing the ravelin and rose at dawn to take a hurried breakfast before heading through the narrow streets to the quay. There they waited with the other soldiers and civilians for places on the boats ferrying the workers across the harbour to the landing stage below the fort. Outside the wall they were issued with picks and joined the slaves already at work cutting a ditch into the rock in front of the ravelin.

For most of the morning they worked in the shade, but as the rays of the sun reached down into the ditch, the heat added to the discomfort of the constant chinking of the picks, the swirling dust and the ache of tired limbs. The glare of the sun was harsh enough to make the men squint, and it steadily burned exposed skin as the workers swung their picks under the burden of their sweat-soaked tunics. At noon they climbed out of the ditch and slumped in the shade of the awnings. They took their midday meal from the boys who had emerged from the fort carrying pitchers of watered wine and baskets of bread and roundels of a hard goat’s cheese made locally. These were handed to the soldiers and the Maltese while the slaves sat in the open and were fed warm gruel from a tureen, one ladle per man, slopped into battered leather cups. These were thrust into the soiled hands of each slave and, still chained in pairs, they squatted down to savour the paltry rations that kept them alive and able to work, and no more. They were barefoot and dressed in rags stained with their own filth. Unkempt hair hung in knotted locks about their bearded faces and their features were gaunt.

On the first day Richard had regarded the slaves with abject pity and when they had settled to eat he chewed slowly at his bread for a while before he spoke to Thomas.

‘Those slaves, they look more like animals than men.’

Sir Martin chuckled as he chewed on a strip of salted beef. He swallowed and cleared his throat. ‘They’re worse than animals, young Dick.’

He spoke loudly so that the nearest of the slaves would hear him. One of them, fairer skinned than the others, looked up at the insult and glared fiercely from beneath his matted locks of dust-grey hair but kept his silence.

‘They’re still humans,’ said Richard.

Sir Martin shrugged. ‘Whatever they are, they’re the enemy, the enemy of our faith, and they would slaughter us without mercy had they the chance. And you, Dick, are a squire and you will treat me with due deference.’

‘I am Sir Thomas’s squire,’ Richard replied.

Читать дальше