There was no time to grieve, no counseling, no time off. Keeping busy was the only thing that was keeping me going. It was the best medicine I had.

Mrs. Kennedy was staying busy, too. She knew she had to move out of the White House—the Johnsons had told her to take her time, but she said she would leave after Thanksgiving, on December 6. There were so many decisions that had to be made, so much for her to think about. Even though she had the help of Mary Gallagher, and Provi, as well as her staff and the president’s staff, the final decisions were all hers to make. Where to live? What to do with the dogs, the horses? But first, she had to go see the president’s father in Hyannis Port.

On Thursday, November 28, Agent Bob Foster and I took Mrs. Kennedy, Caroline, and John to Arlington to visit the grave site. Mrs. Kennedy’s sister Lee, Provi, and Miss Shaw came along. To see the children at the grave of their father—hollow eyes, a three-year-old’s questions, no more rides on the helicopter. It was gut-wrenching. It was Thanksgiving Day.

Agents Landis, Meredith, and Wells had flown ahead to the Cape, and after our brief visit to Arlington, we boarded an Air Force aircraft at Andrews to Hyannis Port. It was an extremely emotional time. Mrs. Kennedy was so close to the ambassador and always before, her visits had been a shining light in his days. Now there was no light in anyone’s eyes. This was the third child Ambassador and Rose Kennedy had lost in violent death. Son Joe in World War II, daughter Kathleen, known as “Kick,” in an airplane crash, and now the president to an assassin’s bullet. What was there to be thankful for?

Paul and I and the children’s agents had assumed we would stay with Mrs. Kennedy and the children until she left the White House. After that, we didn’t know what was going to happen. None of us could bear the thought of leaving them.

SUNDAY, DECEMBER 1, we headed back to Washington. Earlier in November, my wife, Gwen, had found a new apartment in Alexandria—one with more space, for just a few dollars more a month. Unbeknownst to me, George Dalton and Jim Bartlett, two Navy men that handled the boats at Hyannis Port—Jim had been the one who had valiantly tried to teach me to water-ski—had shown up on the doorstep and helped Gwen move. I arrived home to the new apartment, piled high with boxes, and beyond grateful for the kindness of two friends.

The next morning, back at the White House, I received a call from Chief Jim Rowley.

“Clint,” Mr. Rowley said, “there is going to be a ceremony tomorrow morning at eleven o’clock in the fourth-floor conference room in the Treasury Building. You are going to receive the Treasury Department’s highest award for bravery. Secretary Douglas Dillon wants you there at ten-thirty. Your wife and children are invited to attend as well.”

“Okay,” I said.

“Mrs. Kennedy plans to be there,” Rowley added. “Congratulations, Clint.”

I didn’t know what to say. Why am I getting an award? I had heard that Rufus Youngblood, the agent who was with Lyndon Johnson in Dallas, was getting an award. He had jumped on top of the vice president and shielded him from the sniper. He was successful.

I don’t deserve an award. The president is dead.

I didn’t know what to say.

“Thank you,” I finally said.

I hung up the phone and told Paul what the chief had said. Paul congratulated me, but he knew how I felt.

I called home to tell Gwen.

“It looks like you are finally going to meet Mrs. Kennedy,” I said.

THE NEXT DAY, I arranged for Gwen to park on West Executive Avenue—the driveway of the White House. When she and the boys arrived, I walked out to meet them, and together we walked next door to the Treasury Building.

There was a small room next to the fourth-floor conference room. Paul Landis had brought Mrs. Kennedy, her sister, Lee, and the president’s sisters Jean Smith and Pat Lawford. I was surprised to see them there—the president’s sisters.

I introduced them to my family and Mrs. Kennedy said, “You have such fine-looking young sons, Mr. Hill.”

I looked into her eyes, still so filled with pain. Did mine look the same?

“Thank you, Mrs. Kennedy. They are good boys.”

At eleven o’clock, we went into the conference room for the ceremony. Some of the press were there. They snapped pictures and took notes as Treasury secretary Douglas Dillon made a speech and presented me with the award. I was embarrassed by all this undeserved and unwanted attention, but I accepted the award and thanked Secretary Dillon, as Mrs. Kennedy stood and watched.

My family went home, and I went back to my office, glad it was over.

FRIDAY, DECEMBER 6, was moving-out day. Two good friends of President and Mrs. Kennedy, Mr. and Mrs. Averell Harriman, had graciously offered their home in Georgetown as a temporary residence to Mrs. Kennedy and the children. Everything had been packed and sorted, with most of the belongings being sent into storage until Mrs. Kennedy decided where she and the children would live on a permanent basis.

President Johnson had also decided to award the Medal of Freedom, posthumously, to John F. Kennedy, at a ceremony in the State Dining Room, on this day. As Attorney General Robert Kennedy accepted the award on behalf of his brother, Mrs. Kennedy watched, sitting in a small adjacent room, behind a folding screen, her presence unannounced until the ceremony was over.

Everything had been packed and loaded into trucks. Now it was time to say good-bye. Mrs. Kennedy said good-bye to Chief Usher J. B. West and the household staff—staff that had grown to love John and Caroline. It had been such a joy to have children in the White House. Throughout the entire house, from the upstairs maids to the stewards in the Navy Mess, tears were flowing.

A few days earlier, Secret Service Chief Jim Rowley had called me into his office.

“Clint,” he said, “President Johnson has requested the Secret Service provide protection for Mrs. Kennedy and the children for at least one more year. We have agreed to do so.”

“I’m glad to hear that, Mr. Rowley. I think it’s a good decision.”

“The president told Mrs. Kennedy, and said she could have any agents she wanted. Take her pick.”

I nodded. A lump filled my throat. I would do whatever Rowley requested—he was my boss. I would understand completely if she didn’t want me. Every time she sees me, it must bring back the horrible memories of that day, that dreadful day in Dallas. But I couldn’t imagine not being with her.

“Clint, Mrs. Kennedy didn’t hesitate. She wants Bob Foster, Lynn Meredith, and Tom Wells to stay with the children.”

I nodded. Held my breath.

“And for herself, she said there was no choice to be made at all. She wants Paul Landis and Clint Hill.”

Tears welled in my eyes.

“Thank you, Mr. Rowley. Thank you.”

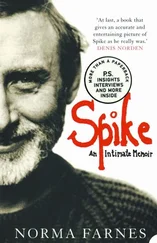

Clint Hill, Mrs. Kennedy, and Caroline arrive at Harriman residence, 12/6/63

So on December 6, as Mrs. Kennedy and the children moved out of the White House, so did I. I would no longer have my office in the Map Room. Jerry Behn said Paul and I could share a desk in his office temporarily, but we’d have to figure something else out. We were no longer on the White House Detail.

Mrs. Kennedy, Miss Shaw, Caroline, and John got into the limousine at the South Portico and we drove from the White House together for the last time. It was quiet. Nothing was said. There was just a heavy sadness inside all of us.

The Harriman house was at 3038 N Street Northwest—just three blocks down from the house where Mrs. Kennedy and I first met. As we drove through the narrow streets with the historic redbrick homes on each side, the memories came flooding back. Three years earlier, she was eight months’ pregnant, and I was so disappointed to have been given this assignment.

Читать дальше