Dedication

To Clive Room

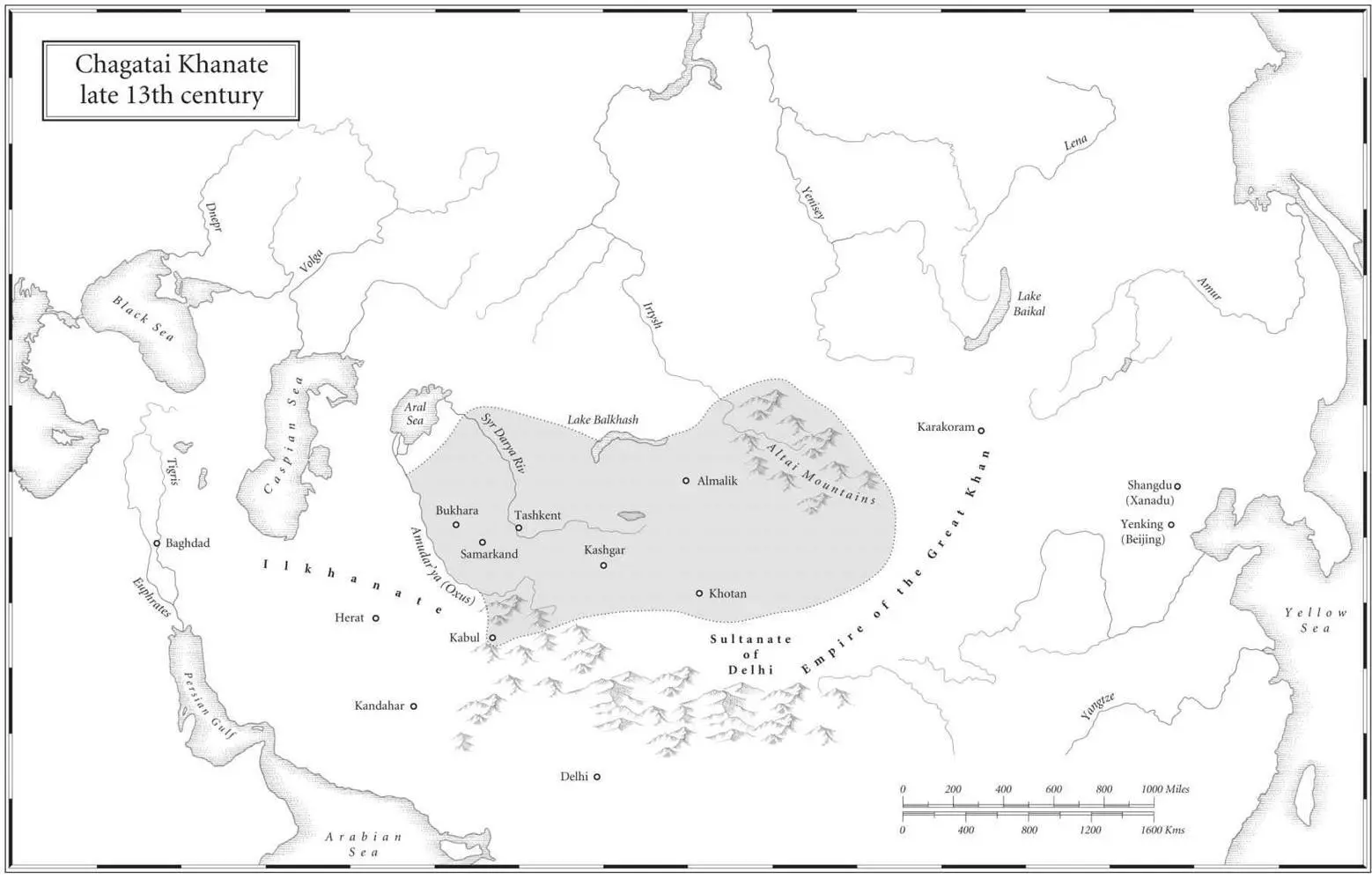

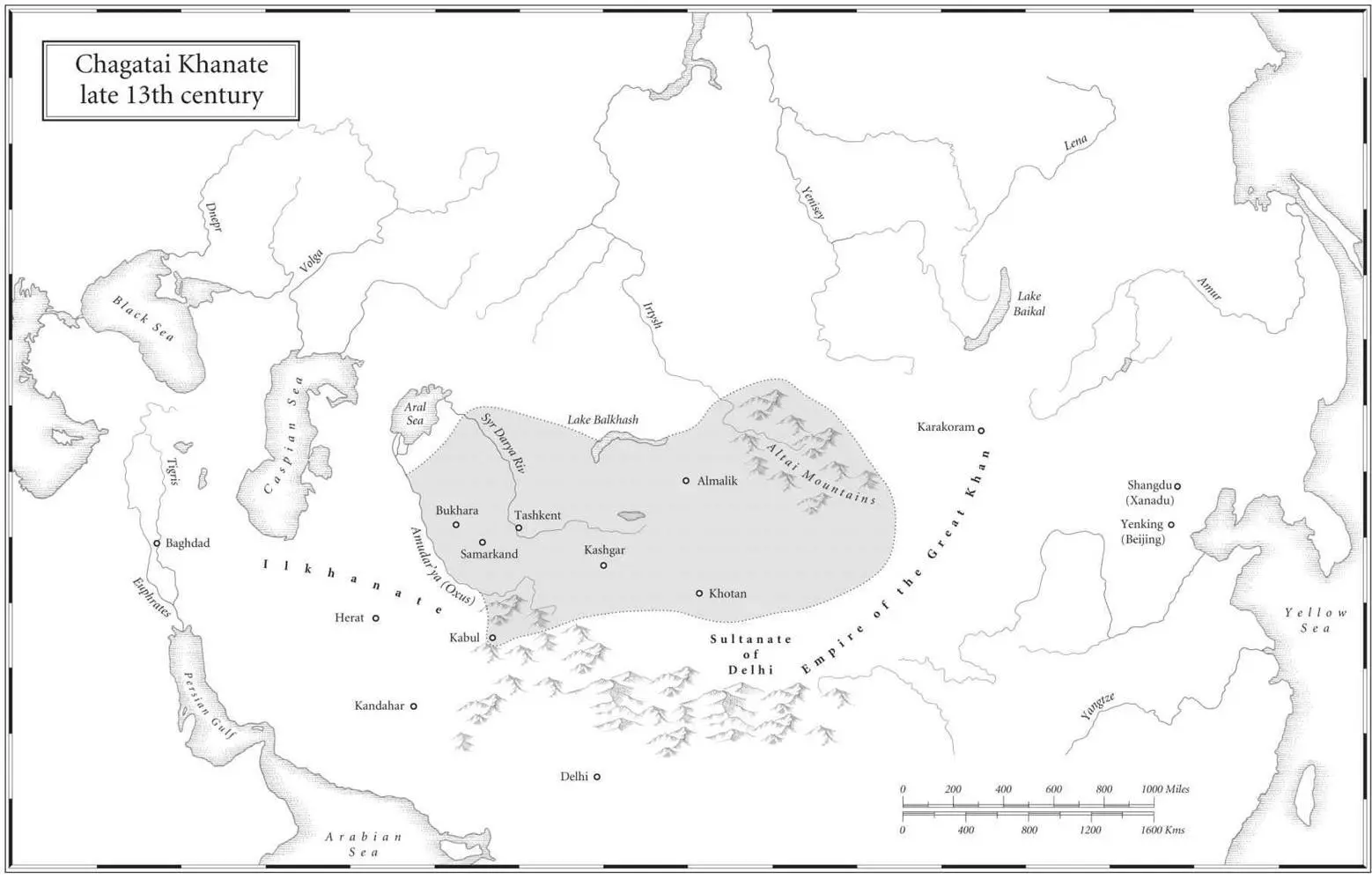

Map

MAIN CHARACTERS

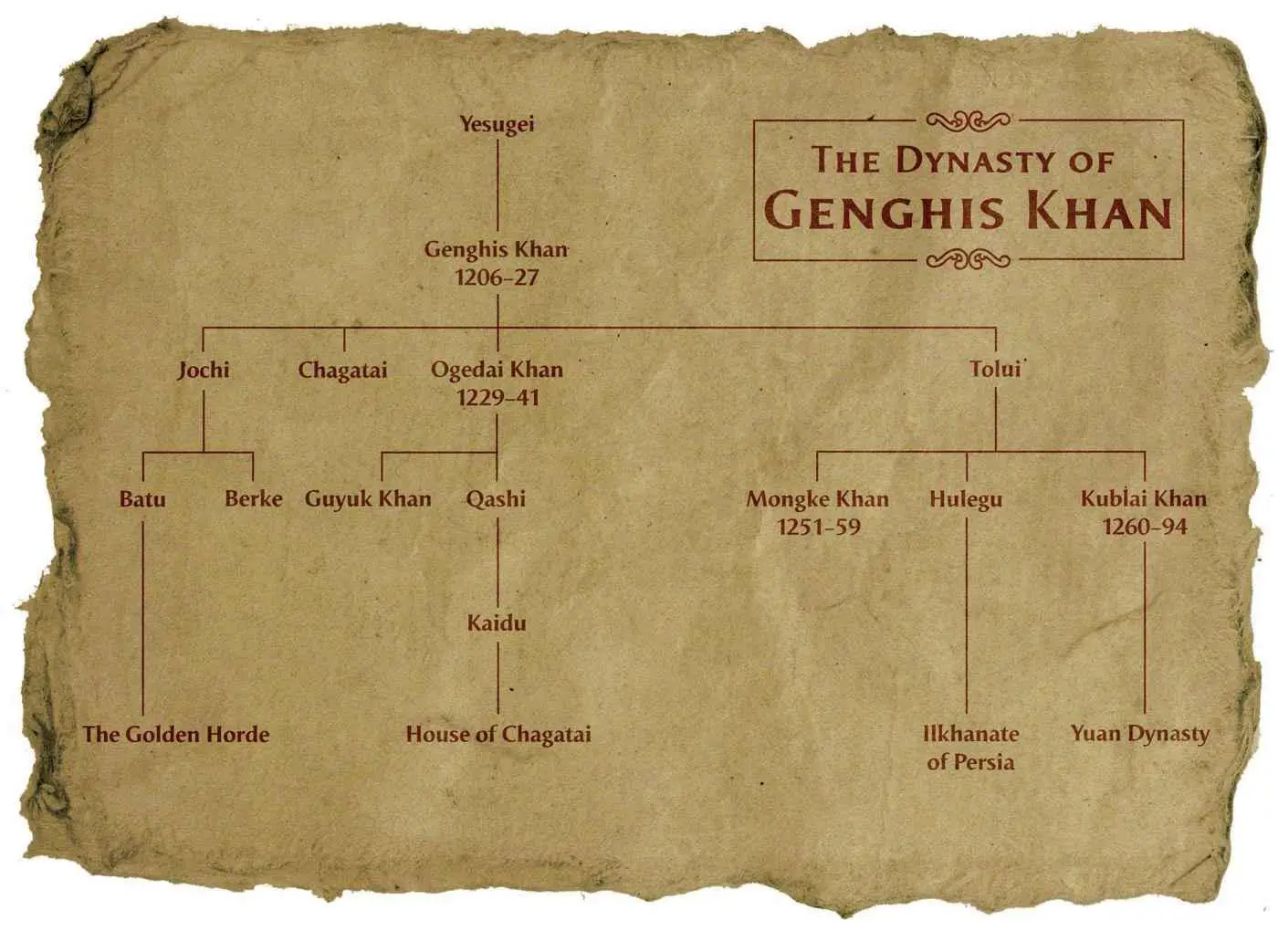

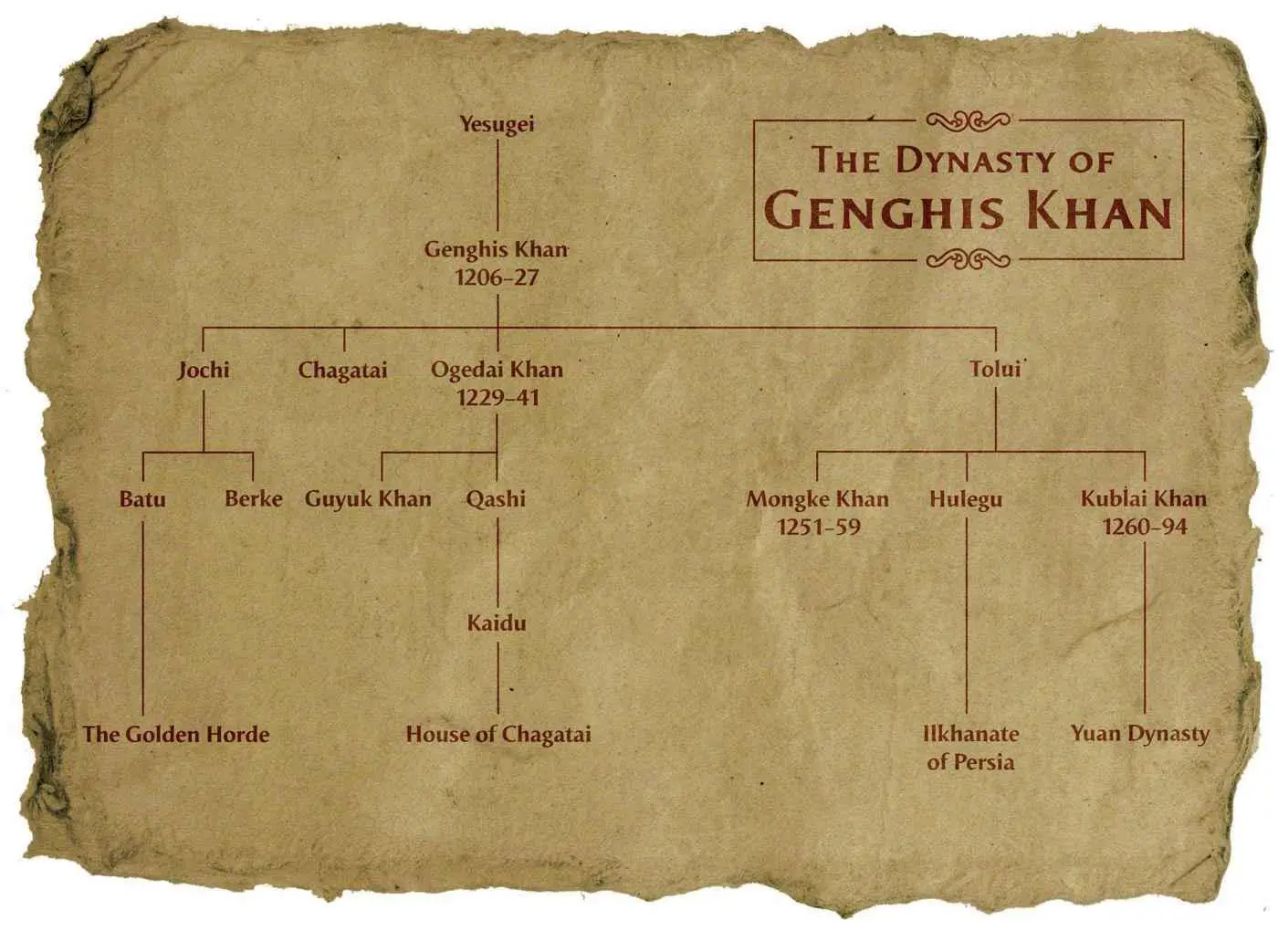

Mongke, Kublai, Hulegu and Arik-Boke

Four of the grandsons of Genghis Khan.

Guyuk

Son of Ogedai Khan and Torogene.

Batu

Son of Jochi, grandson of Genghis. Becomes Russian lord.

Tsubodai

The great general of Genghis and Ogedai Khan.

Torogene

Guyuk’s mother, who ruled as regent on the death of Ogedai Khan.

Sorhatani

Mother to four grandsons of Genghis - Mongke, Kublai, Hulegu and Arik-Boke. Wife to Tolui, the youngest son of Genghis, who gave his life to save Ogedai Khan.

Baidur

Grandson of Genghis. Son to Chagatai, father to Alghu. Ruler of the Chagatai Khanate based around the cities Samarkand and Bukhara.

PART ONE

AD 1244

CHAPTER ONE

A storm growled over Karakorum city, the streets and avenues running in streams as the rain hammered down in the darkness. Outside the thick walls, thousands of sheep huddled together in their enclosures. The oil in their fleeces protected them from the rain, but they had not been led to pasture and hunger made them bleat and yammer to each other. At intervals, one or more of them would rear up mindlessly on its fellows, forming a hillock of kicking legs and wild eyes before falling back into the squirming mass.

The khan’s palace was lit with lamps that spat and crackled on the outer walls and gates. Inside, the sound of rain was a low roar that rose and fell in intensity, pouring as solid sheets over the cloisters. Servants gazed out into the yards and gardens, lost in the mute fascination that rain can hold. They stood in groups, reeking of wet wool and silk, their duties abandoned for a time while the storm passed.

For Guyuk, the sound of the rain merely added to his irritation, much as a man humming would have interrupted his thoughts. He poured wine carefully for his guest and stayed away from the open window where the stone sill was already dark with wetness. The man who had come at his request looked nervously around at the audience room. Guyuk supposed its size would create awe in anyone more used to the low gers of the plains. He remembered his own first nights in the silent palace, oppressed by the thought that such a weight of stone and tile would surely fall and crush him. He could chuckle now at such things, but he saw his guest’s eyes flicker up to the great ceiling more than once. Guyuk smiled. His father Ogedai had dreamed a great man’s dreams when he made Karakorum.

As Guyuk put down the stone jug of wine and returned to his guest, the thought tightened his mouth into a thin line. His father had not had to court the princes of the nation, to bribe, beg and threaten merely to be given the title that was his by right.

‘Try this, Ochir,’ Guyuk said, handing his cousin one of two cups. ‘It is smoother than airag.’

He was trying to be friendly to a man he barely knew. Yet Ochir was one of a hundred nephews and grandsons to the khan, men whose support Guyuk had to have. Ochir’s father Kachiun had been a name, a general still revered in memory.

Ochir did him the courtesy of drinking without hesitating, emptying the cup in two large swallows and belching.

‘It’s like water,’ Ochir said, but he held out the cup again.

Guyuk’s smile became strained. One of his companions rose silently and brought the jug over, refilling both their cups. Guyuk settled down on a long couch across from Ochir, trying hard to relax and be pleasant.

‘I’m sure you have an idea why I asked for you this evening, Ochir,’ he said. ‘You are from a good family, with influence. I was there at your father’s funeral in the mountains.’

Ochir leaned forward where he sat, his interest showing.

‘He would have been sorry not to see the lands you went to,’ Ochir said. ‘I did not … know him well. He had many sons. But I know he wanted to be with Tsubodai on the Great Trek west. His death was a terrible loss.’

‘Of course! He was a man of honour,’ Guyuk agreed easily. He wanted to have Ochir on his side and empty compliments hurt no one. He took a deep breath. ‘It is in part because of your father that I asked you to come to me. That branch of the families follow your lead, do they not, Ochir?’

Ochir looked away, out of the window, where the rain still drummed on the sills as if it would never stop. He was dressed in a simple deel robe over a tunic and leggings. His boots were well worn and without ornament. Even his hat was unsuited to the opulence of the palace. Stained with oil from his hair, its twin could have been found on any herdsman.

With care, Ochir placed his cup on the stone floor. His face had a strength that truly reminded Guyuk of his late father.

‘I do know what you want, Guyuk. I told your mother’s men the same thing, when they came to me with gifts. When there is a gathering, I will cast my vote with the others. Not before. I will not be rushed or made to give my promise. I have tried to make that clear to anyone who asks me.’

‘Then you will not take an oath to the khan’s own son?’ Guyuk said. His voice had roughened. Red wine flushed his cheeks and Ochir hesitated at the sign. Around him, Guyuk’s companions stirred like dogs made nervous at a threat.

‘I did not say that,’ Ochir replied carefully. He felt a growing discomfort in such company and decided then to get away as soon as he could. When Guyuk did not reply, he continued to explain.

‘Your mother has ruled well as regent. No one would deny she has kept the nation together, where another might have seen it fly into fragments.’

‘A woman should not rule the nation of Genghis,’ Guyuk replied curtly.

‘Perhaps. Though she has done so, and well. The mountains have not fallen.’ Ochir smiled at his own words. ‘I agree there must be a khan in time, but he must be one who binds the loyalties of all. There must be no struggle for power, Guyuk, such as there was between your father and his brother. The nation is too young to survive a war of princes. When there is one man clearly favoured, I will cast my vote with him.’

Guyuk almost rose from his seat, barely controlling himself. To be lectured as if he understood nothing , as if he had not spent two years waiting in frustration!

Ochir was watching him and he lowered his brows at what he saw. Once again, he stole a glance at the other men in the room. Four of them. He was unarmed, made so after a careful search at the outer door. Ochir was a serious young man and he did not feel at ease among Guyuk’s companions. There was something in the way they looked at him, as a tiger might look on a tethered goat.

Guyuk stood up slowly, stepping over to where the wine jug rested on the floor. He raised it, feeling its weight.

‘You sit in my father’s city, in his home, Ochir,’ he said. ‘I am the first-born son of Ogedai Khan. I am grandson to the great khan, yet you withhold your oath, as if we were bargaining for a good mare.’

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу