Yet now, as dawn edged the world, the king felt his old doubts return. Was it wise to fight? The English prince had accepted humiliating terms, so perhaps France should impose those terms? Yet victory would yield much greater riches. Victory would bring glory as well as treasure. The king made the sign of the cross and told himself that God would prosper France this day. He had confessed his sins, he had been forgiven, and he had been sent a sign from heaven. Today, he thought, Crécy will be avenged.

‘What if the cardinal arranges a truce, sire?’ d’Audrehem interrupted his thoughts.

‘The cardinal can fart for all I care,’ King Jean said.

Because he had made his choice. The English were trapped, and he would slaughter them.

He led the way from the house into a world made grey by the day’s first wolfish light. He put an arm around the shoulder of his youngest son, the fourteen-year-old Philippe. ‘Today, my son, you will fight at my side,’ he said. The boy had been equipped like his father, head to toe in steel. ‘And today, my son, you will see God and Saint Denis shower glory upon France.’ The king lifted his arms so an armourer could strap a great sword’s belt about his waist. A squire held a war axe with a haft decorated with golden hoops, while a groom led a handsome grey stallion that the king now mounted. He would fight on foot like his men, but at this moment, as the dawn promised a bright new day, it was important that men should see their king. He pushed up his helmet’s visor, then drew his polished sword and held it high above his blue-plumed helmet. ‘Advance the banners,’ he ordered, ‘and unfurl the oriflamme.’

Because France was going to fight.

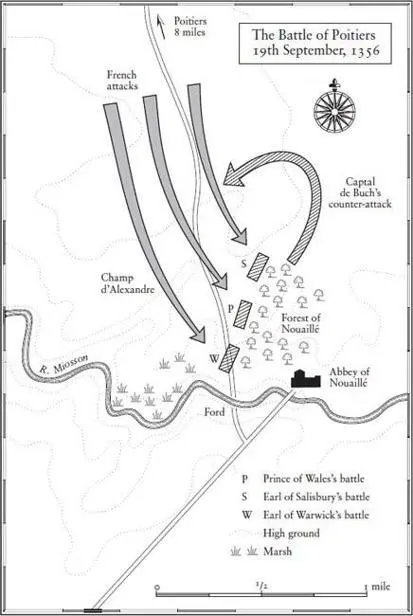

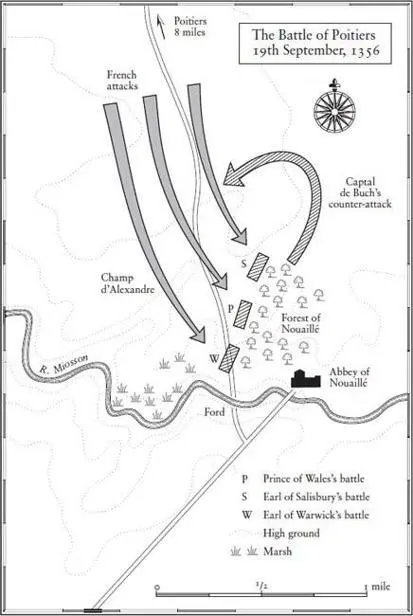

The Prince of Wales, like the King of France, had spent most of the night being armoured. His men had spent it in their lines, beneath their banners. They had been drawn up in battle order for twenty-four hours, and now, in the dawn, they grumbled because they were thirsty, hungry, and uncomfortable. They knew a battle had been unlikely the previous day; it had been a Sunday and the churchmen had proclaimed a Truce of God, though still they had waited in line in case the treacherous enemy broke the truce, but now it was Monday. Rumours flickered through the army. The French numbered twelve thousand, fifteen thousand, twenty thousand. The prince had surrendered them to the French, or the prince had arranged a truce, but despite the rumours there were no orders to relax their vigilance. They waited in line, all but those who went back to the woods to empty their bowels. They watched the skyline to the north and west, looking for an enemy, but it was dark and unmoving there.

Priests moved among the waiting men. They said mass, they gave men crumbs of bread and absolution. Some men ate scraps of earth. From earth they came, to earth they would go, and eating the soil was an old superstition before battle. Men touched their talismans, they prayed to their patron saints, they made the jokes that men always made before battle. ‘Keep your visor lifted, John. Goddamned French see your face they’ll run like hares.’ They watched the wan light grow and the colour come back to a dead world. They talked of old battles. They tried to hide their nervousness. They pissed often. Their bowels felt watery. They wished they had wine or ale. Their mouths were dry. The French numbered twenty-four thousand, thirty thousand, forty thousand! They watched their commanders meet on horseback at the line’s centre. ‘It’s all right for them,’ they grumbled. ‘Who’ll kill a goddamned prince or earl? They just pay the bloody ransom and go back to their whores. We’re the goddamned bastards who have to die.’ Men thought of their wives, children, whores, mothers. Small boys carried sheaves of arrows to the archers who were concentrated at the ends of the line.

The prince watched the western hill and saw no one there. Were the French sleeping? ‘Are we ready?’ he asked Sir Reginald Cobham.

‘Say the word, sire, and we go.’

What the prince wanted to do was one of the most difficult things any commander could attempt. He wanted to escape while the enemy was close. He had heard nothing from the cardinals and he had to assume the French would attack, so his troops would need to hold them off while the baggage and the vanguard crossed the Miosson and marched away. If he could do it, if he could get his baggage across the river and then retreat, step by step, always fending off the enemy attacks, then he could steal a whole day’s march, maybe two, but the danger, the awful danger, was that the French would trap half his army on one bank and destroy it, then pursue the other half and slaughter that too. The prince must fight and retreat, fight and retreat, holding the enemy at bay with a dwindling number of men. It was a risk that made him make the sign of the cross, then he nodded to Sir Reginald Cobham. ‘Go,’ he said, ‘get the baggage moving!’ The decision was made; the dice were rolled. ‘And you, my lord,’ he turned to the Earl of Warwick, ‘your men will guard the crossing place?’

‘We will, sire.’

‘Then God be with you.’

The earl and Sir Reginald galloped their horses south, and the prince, glorious in his royal colours and mounted on a tall black horse, followed more slowly. His handsome face was framed in steel. His helmet was ringed with gold and crested with three ostrich feathers. He paused every few yards and spoke to the waiting men. ‘We will probably fight today! And we shall do in this place what we did together at Crécy! God is on our side; Saint George watches over us! And you will stay in line! You hear that? No man will break the line! You see a naked whore in the enemy ranks you leave her there! If you break ranks the enemy will break us! Stay in line! Saint George is with us!’ Again and again he repeated the words. Stay in line. Don’t break the line. Obey your commanders! Stay together, shield to shield. Let the enemy come to us. Do not break the line!

‘Sire!’ A messenger galloped from the line’s centre where there was a great gap in the thick hedge. ‘The cardinal is coming!’

‘Meet him, find what he wants!’ the prince said, then turned back to his men. ‘You stay in line! You stay with your neighbour! You do not leave the ranks! Shield next to shield!’

The Earl of Salisbury brought the news that the cardinal was offering a further five days of truce. ‘In five days we starve,’ the prince retorted, ‘and he knows it.’ The army had run out of food for men and horses and the presence of the enemy meant that no forage parties could search the nearby countryside. ‘He’s just doing the French king’s bidding,’ the prince said, ‘so tell him to go say his prayers and leave us alone. We’re in God’s hands now.’

The church’s mission had failed. Archers strung their bows. The sun was almost above the horizon and the sky was filled with a great pale light. ‘Stay in line! You will not leave the ranks! Do you hear me? Stay in line!’

Beneath the hill, beside the river where the shadows of the night still lingered, the first wagons moved towards the ford.

Because the army would escape.

PART FOUR

Battle

Fourteen

The axles squealed like pigs being slaughtered at winter’s onset. The carts, wagons and wains, of which no two were alike, lurched on the rough track that led along the river’s northern bank. Most were piled high, though with what it was impossible to tell because rough cloth was strapped over the loads. ‘Plunder,’ Sam said, sounding disapproving.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу