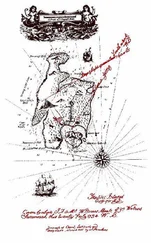

He'd gather a tuft of grass and tie it around with more grass, or he'd break a branch and stick it in the ground to show the way he'd gone.

Often the Indians would bend a living tree to mark the way. From time to time in wandering the woods one will wonder about a tree that grows parallel to the ground for a ways. Chances are it was some marker used by Indians in the long ago.

Pa taught us boys as best he could. He'd find a spot in the deep woods and he'd clear the ground of all leaves, branches, stones, and whatever. Then he'd smooth out the dust, leaving some food, both meat and seeds, in the center. We'd surround it with a circle of branches or stones, and we'd come back each morning to see who'd been there.

It wasn't long until we boys could tell the track of any animal or bird or reptile that crossed the smooth dust. Pa was forever pointing at some tracks or tree or bunch of rocks and asking us what we thought. Happened there, or what was happening. It's an amazing thing how much a boy can learn in a short time.

You found where animals had fought, mated, and died. You learned which animals moved about at night, which would come for meat, and which for seeds or other food.

We got so we just saw things without having to look for them. It was natural to us to know what was happening in the mountains and in the forest. Just as people differ one from another, so do the trees, even the trees of one species.

After a while I put my fire together again and fixed a little food, made fresh coffee, and took time to study the situation. Pa had been in this spot twenty years ago, and things would have looked very different. The older of the fallen trees would have been growing then, and several others within the range of my eyes would have been fair-sized trees. Others, larger and older, might now be gone.

The high winds, snows, and ice of the alpine heights are hard on trees. The bristlecone pine, which seems to survive anything, outlasts the others. This shelf where I had taken refuge would be deep under snow much of the year, and when pa was here some snow might have still been left. To understand his situation I had to bring back the shelf the way it must have been when he saw it.

Surely there'd have been snow where I sat, snow in this pocket and along the side where the shadows stayed almost all day long. He'd have made his notch somewhere here, but the tree might have fallen. It might be this very tree that was rotting away before me, or it might have been burned in campfires or fallen clear over the rim. There were scattered carcasses of trees along the steep slope below the cliff.

Pa respected his boys, respected our knowledge of things, and if he'd had the chance he'd have left us a clue, some hint as to where the gold was, and maybe as to what had become of him.

Had the journal ended with the loss of that daybook? Or had he some other means of writing? I'd better consider that.

I needed Orrin here. He had a contemplative mind and he was a lawyer, a man accustomed to dealing with the trickiness of the human mind. Tyrel would have been a help, too, for Tyrel took nothing for granted. He was a right suspicious man. He liked folks, but never expected much of them. If his best friend betrayed him he'd not be surprised. He figured we were all human, all weak at times, and mostly selfish. And we all, he figured, had traits of nobility, self-sacrifice, and courage. In short, we were folks, people.

Tyrel never held it against any man for what he did. He trusted nobody too much, liked most people, and he was wary. But at a time like this he would have been a help. He had a reasoning, logical brain unhampered by much sentiment.

One thing was a help. We Sacketts bred true. I mean, we bred to type. Like the Morgan horse. Pa used to say he'd known a sight of Sacketts one time and another, and they varied in size, but most of them ran to dark, kind of Indian-like features and to willingness to fight. Even those Clinch Mountain Sacketts, who were a cattle-rustling, moonshining lot, would stand fast in a showdown, and they'd never go back on their word or fail a friend.

They might steal his horse, if it was a good one and chance offered, but they were just as like to stand over his wounded body and fight off the redskins or give him one of their own horses, even their only horse, to get away on.

Logan and Nolan, for example. They were Clinch Mountain Sacketts, and their pa was meaner than a rattlesnake in the blind, but they never walked away from a friend in trouble, or anybody else, for that matter.

Nolan was forted up down in the Panhandle country with some Comanches yonder a-shootin' at him. One of them got lead into him. He nailed that one right through the ears as he turned his head to speak to the other one, and then he wounded the last one. Nolan walked in on him, kicked the gun out of his hand, and stood there looking down at him, gun in his fist, and that Comanche glared right back at him, dared him to shoot, and tried to spit at him.

Nolan laughed, picked that Injun up by the hair and dragged him to his horse. He loaded that Indian on, tied him in place, then mounted his own horse and rode right to that Comanche village.

He walked his horse right in among the lodges and stopped.

The Comanches were fighters. No braver men ever lived, and they wanted Nolan's hair, but they came out and gathered around to see what he had on his mind.

Nolan sat up there in the middle of his mustang, and he told them what a brave man this warrior was, how he had fought him until he was wounded, his gun empty, and then had cussed him and tried to fight him with his hands.

"I did not kill him. He is a brave man. You should be proud to have such a warrior. I brought him back to you to get well from his wounds. Maybe some day we can fight again."

And then he dropped the lead rope and rode right out of that village, walking his horse and never looking back.

Any one of them could have shot him. He knew that. But Indians, of any persuasion, have always respected bravery, and he had given them back one of their own and had promised to fight him again when he had his strength.

So they let Nolan ride away, and to this day in Comanche villages they tell the story. And the Indian he brought back tells it best.

I didn't really have time to contemplate the past. I had mighty little time left and I wanted to find out what happened to pa.

Clouds were making up. Nearly every afternoon there was a brief thundershower high up in the mountains, and now the clouds were gathering. I guess I was feeling kind of pleased about that. I had an idea those folks were new to the high-up hills and if so they were in for a shock.

Rain can fall pretty hard, and of course you're right in the clouds. Right amongst them. Lightning gets to flashing around, and even without it flashing the electricity in the air makes your hair prickle like a scared dog's.

I didn't much relish running around atop that mountain with a rifle in my hands, but it looked like I had it to do.

The bulging dark clouds moved down and began to spatter rain, and I came off that log where I was settin' like a chipmunk headin' for a tree. I went around the tree holding my rifle in one hand, scrambled up the rocks, took a quick look, and ran on the double for that knoll.

If they broke and ran for shelter, I would make it. I started up the knoll knowing that in just about a minute it was going to be all wet grass, slippery as ice. Just as I was topping out on the rise a man raised up, rifle in hand.

He'd no idea there was anybody even close. He was getting set to run for shelter from the rain, I figure, and was taking a quick look before he left; and there I was, coming up out of that drifting cloud right at him.

Neither of us had time to think. My Winchester was in my right hand in the trail position, and when he hove up in front of me I just drove the muzzle at him. It was hanging at my side at arm's length. When that man came up off the ground I swang it forward and there was power behind it.

Читать дальше