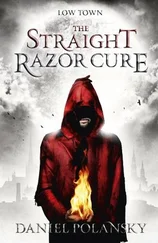

TOMORROW THE KILLING

Daniel Polansky

www.hodder.co.uk

To the Sibs, in order of appearance:

David, Michael, Marisa and Alissa.

1

Man is a puerile creature, easily misled by the superficial. Some fool from the neighborhood, a mark you wouldn’t trust to clean a chamberpot, comes up to you on the street in a clean suit and you find yourself ducking your head and calling him sir. It works backways as well – that selfsame halfwit puts on a uniform and gets to thinking he’s hard, wraps up in a priest’s vestments and mistakes himself for decent. It’s a dangerous thing, pretense. A man ought to know who he is, even if he isn’t proud to be it.

I tugged loose the collar of my dress jacket and wiped sweat from my brow. It was a hot day. It had been a hot week in a hot month, and it didn’t look to be getting cooler. The drawing room wasn’t built for the wave that had baked the city this last month, left wells dry and stray mutts foaming in the alleys. Though for the inhabitants of the mansion I supposed the drought was more a question of ruined outfits and canceled garden parties – what was life and death in Low Town was an inconvenience in Kor’s Heights. Even the weather afflicts the rich differently.

Which is to say it wasn’t just the heat making me sweat, nor my raiment. I didn’t like being here, didn’t like heading this far north, not before nightfall, not at all if I could help it. Even the densest member of the city guard could figure I wasn’t native. So when the footman had come knocking at the door of the Staggering Earl the day prior – not a runner asking for a few fistfuls of product, not a contact begging a favor – but a full-fledged steward, dressed in crimson livery and looking as out of place as an abbess in a whorehouse, I’d nearly sent him home. But curiosity made me open his message, that almost virtue which leads men to ruin and scrapes the ninth life off cats. The letter requested my attendance at a meeting the next morning, and it was signed ‘General Edwin Montgomery’, and by the time I got to the end of it I was wishing one of the local thugs had upended the emissary before I’d found another way to fuck myself. Given what was between us, I couldn’t very well refuse his entreaty – though looking back on how things unfolded, it would have been better for everyone if I had.

It probably doesn’t need to be said that I’m no great respecter of authority, nor of that particular brand of idiots who had sent me and several hundred thousand other souls out to die during the Great War – but Montgomery was all right. More than all right, he was a fucking legend, maybe the only man who’d ever borne high rank who deserved it. Most of his colleagues hadn’t ever so much as seen the front, happy to set their headquarters in captured châteaux, working their way through the enemies’ wine cellars and tallying up casualty rolls in grim little ciphers. After it was over, when the glow of victory began to fade and the backlash against the high brass crested, Montgomery had been one of the few whose name never started to rot. At one point there had been talk of making him the Minister for War, maybe even High Chancellor. But then, we’d all hoped to be something else, at some point.

I hadn’t seen him for more than ten years. I hadn’t ever anticipated our meeting again, and was far from thrilled to find myself wrong.

I stifled an urge to roll a cigarette and tried not to fidget in my chair. Montgomery’s servant, a densely built Vaalan, watched me from his position in front of his master’s door. He was a military man, that was easily caught, from his proximity to the general and the coiled vigor of his physique. His eyes were etched unforgiving below the granite ledge of his forehead. His face seemed well suited to taking a beating, and his arms and shoulders well suited to delivering one. In short, I didn’t imagine he had trouble chasing vagrants away from the back door – but, as with all of us, age was gaining. His hair, snipped low in a regulation short-cut, was more salt than pepper, and if only the faintest hint of flesh covered his dense core, still I suspected it was a half-stone more than he’d ever carried.

His name was Botha. I was impressed with myself for remembering it, given that I’d met him all of twice. In fact, I was having difficulty squaring our relatively limited acquaintance with the bleak stare he was aiming in my direction, the sort one reserves for the man who raped your sister, or at least killed your dog.

‘Been a while,’ I offered.

Botha grunted. I got the sense that as far as he was concerned, the pause could have extended out a good ways longer.

‘You think you could rustle me up some finger sandwiches? The little ones, with cucumber and a bit of mutton?’

Having perfected his indifference against actual arrows, their rhetorical equivalent had little effect. He scuffed an imaginary bit of dirt off his shoulder.

‘Isn’t it appropriate to offer refreshments when entertaining guests?’

‘You aren’t a guest,’ he muttered, the barest break in a steady and uncompromising countenance.

‘Well, I’m here, aren’t I? That would make me company or family, and either way I’d like a finger sandwich.’

A bell rang from within the room, so I never did get to find out whether I had done enough to rile him. But I wouldn’t have bet against myself – I can be an aggravating motherfucker when I set my mind to it. Botha opened the door and slipped inside. He came back out after another moment, then waved to me.

‘I’d tip you, but I’m all out of ochres, and I wouldn’t want to insult your service with silver.’

‘Maybe I’ll get compensation some other day,’ he said, slipping out sidelong as I brushed past him.

I stopped short, both of us squeezed awkwardly into the door-frame. ‘I’m diligent in repaying debts.’

He allowed me to pass, then ducked his shoulders and nodded, mimicking the actions of a servant. The master of the house awaited, and I headed inside to meet him.

The study looked like what it was. Ebony bookshelves ran to the corners, filled by an appropriately dignified selection of leather-bound tomes. A stone fireplace took up most of the back wall, even its memory too hot for the day. A solid, uncluttered desk stood in the center, and the man himself sat behind it. It was a nice set-up – for the price of the furniture alone you could buy a half-square block of Low Town. But for a man whose wealth could have afforded him the most opulent luxuries, it was distinctly in the low key.

I’d met the general in Nestria some fifteen years prior, though I didn’t imagine he remembered it. He’d toured the lines one night when I was sitting guard. That was during the first winter of the war, when you could never build a fire big enough to ward off the cold, and the first thing you did on waking was check your toes for frostbite. He’d come pacing in from the darkness, only an adjutant for company, dressed like any one of us grunts, shit on his boots and a greatcoat covered in mud. It had meant something to me. It had meant something to a lot of us.

The general was past middle age when he’d held a command during the war, and true to form, the years hadn’t left him any younger. But neither had they taken from him the towering sense of self-possession I’d noticed even during the first few seconds I’d seen him, trudging through the icy rain – as if the weather, not to say the enemy, were factors beneath his contempt. If anything age had sharpened it, the gradual withering of his body rendering clearer the absolute control that he maintained over it.

Читать дальше