T. C. Boyle

When the Killing's Done

For Kerrie, who tramped the ridges and braved the ghosts

And God blessed them, and God said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.

— Genesis 1:28

I would like to thank Lotus Vermeer, Marla Daily, Kate Faulkner, Rachel Wolstenholme, Marie Alex, Jim Perry, Jay Brennan, Stephanie Mutz and Mike DeGruy for their kind assistance with the research for this book. In addition, I would like to express my debt of gratitude to the historians and memoirists of the Channel Islands, whose accounts proved invaluable to the unfolding of this narrative, particularly those of Michel Peterson, Marla Daily, John Gherini, Tom Kendrick, Clifford McElrath, Margaret Eaton and Helen Caire.

Portions of this book appeared previously, in slightly different form, in McSweeney’s, Orion and The Iowa Review .

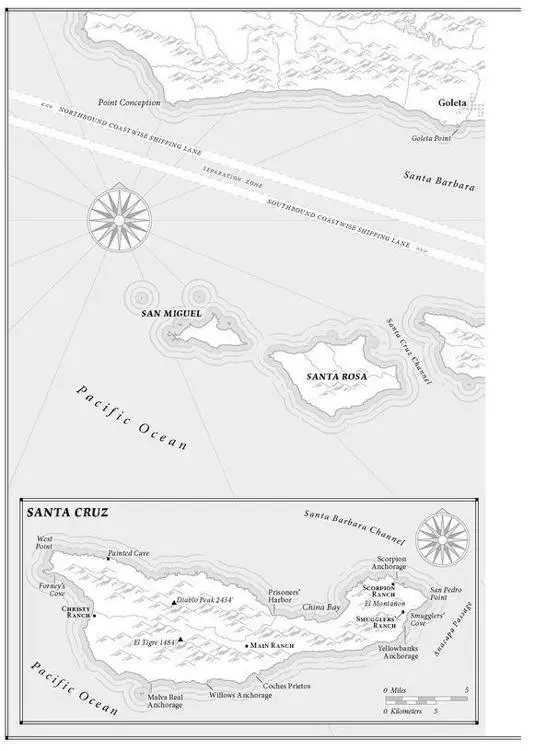

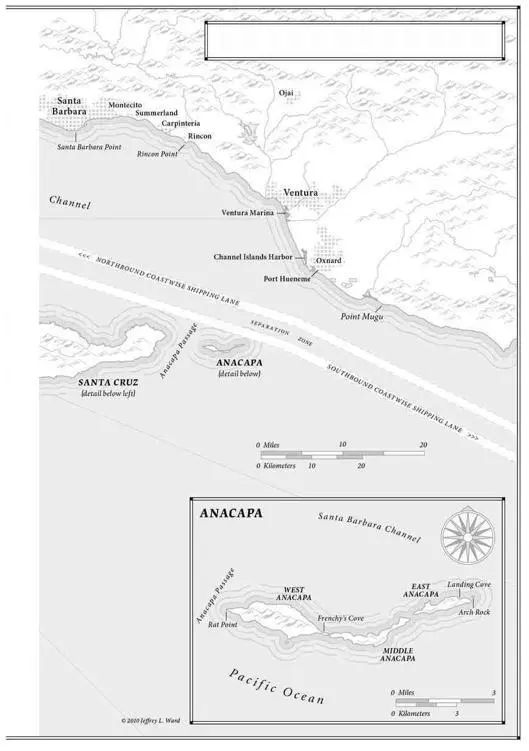

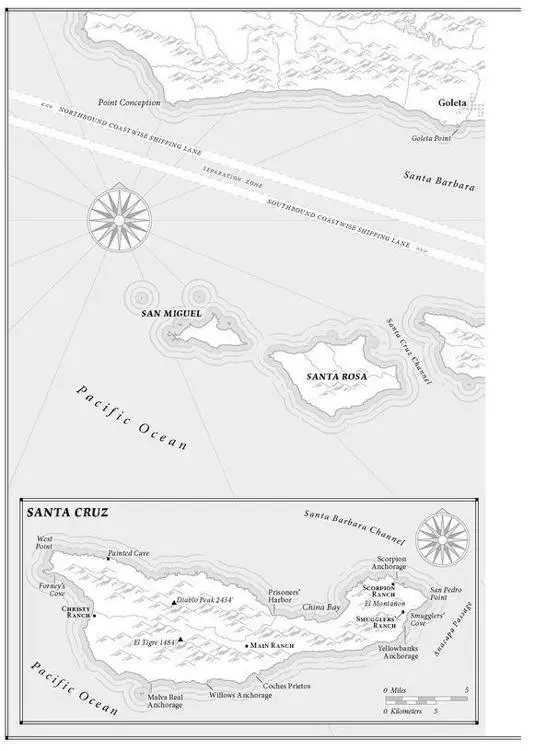

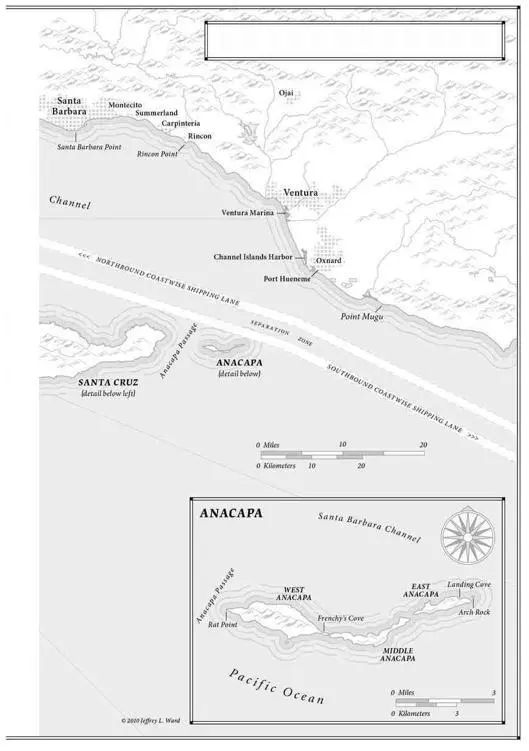

The Northern Channel Islands

The Wreck of the Beverly B

P icture her there in the pinched little galley where you could barely stand up without cracking your head, her right hand raw and stinging still from the scald of the coffee she’d dutifully — and foolishly — tried to make so they could have something to keep them going, a good sport, always a good sport, though she’d woken up vomiting in her berth not half an hour ago. She was wearing an oversized cable-knit sweater she’d fished out of her husband’s locker because the cabin was so cold, and every fiber of it seemed to chafe her skin as if she’d been flayed raw while she slept. She hadn’t brushed her hair. Or her teeth. She was having trouble keeping her balance, wondering if it was always this rough out here, but she was afraid to ask Till about it, or Warren either. She didn’t know the first thing about handling a boat or riding out a heavy sea or even reading a chart, as the two of them had been more than happy to remind her every chance they got, and Till told her she should just settle in and enjoy the ride. Her place was in the kitchen. Or rather, the galley. She was going to clean the fish and fry them and when the sun came out — if it came out — she would spread a towel on top of the cabin and rub a mixture of baby oil and iodine on her legs, lie back, shut her eyes and bask till they were a nice uniform brown.

It was only now, the boat pitching and rolling and her right hand vibrant with pain, that she realized her feet were wet, her socks clammy and clinging and her new white tennis shoes gone a dark saturate gray. And why were her feet wet? Because there was water on the galley deck. Not coffee — she’d swabbed that up as best she could with a rag — but water. Salt water. A thin bellying sheet of it riding toward her and then jerking back as the boat pitched into another trough. She would have had to sit heavily then, the bench rising up to meet her while she clung to the tabletop with both hands, as helpless in that moment as if she were strapped into one of those lurching rides at the amusement park Till seemed to love so much but that only made her feel as if her stomach had swallowed itself up like in that cartoon of the snake feeding its tail into its own jaws.

The cuffs of her blue jeans were wet, instantly wet, the boat riding up again and the water shooting back at her, more of it now, a shock of cold up to her ankles. She tried to call out, but her throat squeezed shut. The water fled down the length of the deck and came back again, deeper, colder. Do something! she told herself. Get up. Move! Fighting down her nausea, she pulled herself around the table hand over hand so she could peer up the three steps to where Till sat at the helm, his bad arm rigid as a stick, while Warren, his brother Warren, the ex-Marine, bossy, know-it-all, shoved savagely at him, fighting him for the wheel. She wanted to warn them, wanted to betray the water in the galley so they could do something about it, so they could stop it, fix it, put things to right, but Warren was shouting, every vein standing out in his neck and the spray exploding over the stern behind him like the whipping tail of an underwater comet. “Goddamn you, goddamn you to hell! Keep the bow to the fucking waves!” The ship lurched sideways, shuddering down the length of it. “You want to see the whole goddamn shitbox go down. .?”

Yes. That was the story. That was how it went. And no matter how often she told her own version of what had happened to her grandmother in the furious cold upwelling waters of the Santa Barbara Channel in a time so distant she had to shut her eyes halfway to develop a picture of it — sharper and clearer than her mother’s because her mother hadn’t been there any more than she had, or not in any conscious way — Alma always drew her voice down to a whisper for the payoff, the denouement, the kicker: “Nana was two months’ pregnant when that boat sank.”

She’d pause and make sure to look up, whether she was telling the story across the dining room table to one of her suitemates back when she was in college or a total stranger she’d sat next to on the airplane. “Two months’ pregnant. And she didn’t even know it.” And she’d pause again, to let the significance of that sink in. Her own mother would have been dead in the womb, washed ashore, food for the crabs, and she herself wouldn’t exist, wouldn’t be sitting there with her hair still wet from the shower or threaded in a ponytail through the gap in back of her baseball cap, wouldn’t be teasing out all the nuances and existential implications of the story that was the tale of the world before her, if it weren’t for the toughness — in body, mind and spirit — of the woman she remembered only in her frailty and decrepitude.

Of course, she felt the coldness of it too, the aleatory tumble that swallowed up the unfit and unlucky while the others multiplied. And if there were a thousand generations of shipwrecks in the same family, would their descendants develop gills and webbed toes or would they just learn to stay ashore and ignore those seductive unfettered islands glittering out there on the horizon? She was alive, in the crux of creation, along with everything else sparking in the very instant of her telling, and one day she’d have children herself, add to the sum of things, work the DNA up the ladder. Her mother’s father was dead. And his brother along with him. And her mother’s mother should have been dead too. That was the thing, wasn’t it?

The month was March, the year 1946. Alma’s grandfather — Tilden Matthew Boyd — was six months home from the war in the Pacific that had left him with a withered right arm shorn of meat above the elbow, nothing there but a scar like a seared omelet wrapped around the bone. Her grandmother, young and hopeful and with hair as dark and abundant as her own, broke a bottle over the bow of the Beverly B. while Till, restored to her from the vortex of the war in a miraculous dispensation more actual and solid than all the cathedrals in the world, sat at the helm and the gulls dipped overhead and the clouds swept in on a northwesterly breeze to chase the sun over the water. Beverly was happy because Till was happy and they ate their sandwiches and drank the cheap champagne out of paper cups in the cabin because the wind was stiff and the chop wintry and white-capped. Warren was there too that first day, the day of the launching, a walking Dictaphone of unasked-for advice, ringing clichés and long-winded criticism. But he drank the champagne and he showed up two weekends in a row to help Till tinker with the engines and install the teak cabinets and fiddle rails Till had made in the garage of their rented house that needed paint and windowscreens for the mosquitoes and drainpipes to keep the winter rains from shearing off the roof and dousing anybody standing at the front door with a key in her hand and a load of groceries in both her aching arms. But Till had no desire to fix the house — it didn’t belong to them anyway. The Beverly B. , though — that was a different story.

Читать дальше