“You’re not helping your case,” Ress commented bleakly. “Or your credibility.” His expression was humourless. “My priority’s the kid. And no way am I taking tales of monsters into a CityWarden’s hearing without proof. You’re jesting.”

“No,” Roderick said softly. “I’m not.”

Tension rose like the edge of the sunrise. Feren cried out, wordless and laden with pain.

And then came the shock.

An edge of a memory, a cold point in Roderick’s heart, something that was there-and-gone, terrifying but utterly formless. He knew it, he knew it, and he had no idea why. It was an after-echo of a nightmare, chill and tantalising, shivering through his skin – and even as he was reaching to understand it, it had faded into the morning.

What...?!

His breath had congealed and he found he was shaking, his hands palsied with a desperate need to grab this thing, to see it and name it.

Fired by a rush of frustration, he said, “This is no story! How can I find words to frame this? Ecko is here ; he brings darkness and fire and strength the likes of which I’ve never seen! He understands my tale, my vision, the world’s lost memory.” The words had a bitterness he could barely suppress. “I feel the Count of Time at my back. Call me madman if you will, insane prophet – whatever name you choose to give me –” he came forwards, the early light in his eyes “– but take this tale to Jade – tell him everything!”

“Tell him yourself!” Triqueta said.

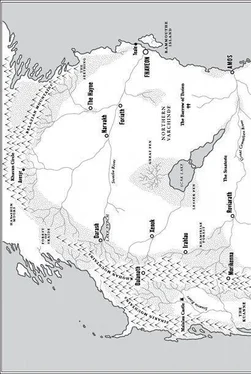

“I must carry this to Fhaveon – to Rhan, and to the Council of Nine. To the Foundersson himself!”

“Gods,” Ress said, sharp as a punch in face. “They’ll lock you up.”

The Bard’s plea tumbled into silence; it fell like a grey pebble in the pre-dawn light and rolled, disregarded, across the courtyard. For a moment, he wanted to rail with hopeless, helpless, timeless fury, I am a Guardian of the Ryll, such instincts are my training and my strength. I can feel the truth of them in my blood and bone. How can I make you understand?

But he knew that such words meant nothing – that they would fall forlorn and spin forgotten across the stone of The Wanderer’s yard.

Triqueta stared at him for a moment, then turned away.

“Roderick, with respect.” Ress gave a short sigh. “Your sincerity is apparent – I’m trying to help you. You can’t just walk into the Council in Fhaveon with some injured kid’s loco rumour – ‘here be monsters’.”

“I have to. And equally, you must rouse CityWarden Jade,” Roderick said.

“This is crazed!” Ress spread his hands helplessly. “Feren’s badly hurt, his mind could have played any number of jests on him. Roderick, with respect, I don’t understand why you’re –”

“Then take it this way,” Roderick said. “Such alchemy is no figment. Tales of ancient Tusien say the city sired monstrosities – creatures of crossed flesh that dwelled in captivity for the amusement of all. Those creatures were crafted, not born. Where do you think our chearl first came from? Our bretir? Our –” his lips twisted “– nartuk? Who is to say that the Monument doesn’t hold Tusien’s memory; that somewhere this lore has not been preserved, uncovered? If you will not heed my fears, then heed my facts.”

“They’re sagas .” Ress’s words were like the snapping of a trap.

Roderick’s grin had an edge of mania. “There is truth in every tale.”

“Look, I’ve had enough of this.” Ress picked up the wagon’s traces. “You can’t attach half a man to half a horse. That’s the end of it. No amount of regurgitated legend is going to make me stand in front of Larred Jade and tell him otherwise. If – when – Feren wakes up –”

“Then give me an alternative.” Roderick smoothed the nose of the chearl in the wagon traces. “If there was no monster, what happened to the boy? Where’s his teacher, Amethea?”

“Boys.” Triq was watching the sky. “Quit squabbling, will you? We’re running out of time.”

Feren muttered again, his face was white and sweating.

Ress turned on Triqueta, the paling sky glittering like shards in his eyes. “Why didn’t you leave him?”

“What?” Triqueta was rocked back by the question. “You know I wouldn’t – not even by my desert blood, none of us would. What the rhez kind of question is that?”

Ress shifted on the wagon seat. “I’m not Banned-born. I was a scholar, learned a lot about people – before it went wrong and Syke gave me refuge. The Banned, Triq, you’re forthright, you act before you think, you speak your mind, you –” a rat scuttled across the cobbles, making Triq’s mare snort and sidestep “– sometimes, you can be very naïve.”

“Oh naïve ?” Triq spat, indignant. “I’ve spent my whole damned life with the Banned, worked for every CityWarden that’d compensate me and done dirtier deeds that I’d ever tell you. Naïve! What’ve you done?”

“Learned.” Ress gave her a wry half-smile. “Enough to know that you can’t achieve the impossible .” He glanced at the Bard. “So what’s left?”

Triqueta gaped. “You mean – Feren made this up ?”

“Think about it.” Ress cut her short. “He’s a good apothecary – good enough to know he’ll die. And certainly, something’s happened to his teacher. So, what’s more likely?”

“Oh for Gods’ sakes,” Triq said. “He’s a kid, he’s hurt and he’s worried about his friend. Besides, that arrow shaft had to’ve come from the biggest Gods-be-damned bow I’ve ever seen. The Archipelagan Redfeather don’t make bows that size! And you said yourself that taer grows at the Monument – !”

“You’re stupid .” The slightly sullen, sulky voice was Jayr’s. “All of you.” Startled, they turned to look at her, at her elaborate, deliberate scarring shining white under the dying moons.

The girl was looking at her hands – at the multitude of long-healed breaks in her fingers, at the calluses and scars. She spat out a chewed piece of fingernail and shot them all a resentful, adolescent look. “You know something?” She glowered around at them. “This is all horseshit. Talk, talk talk. He’s young and he’s scared, and his friend is still out there. We should ride to the Monument ourselves and tear it down if we have to.” She looked fully capable of ripping it stone from stone.

“We can’t,” Ress said gently. “Not until Feren’s safe.”

“You must speak to Jade,” Roderick said. “Persuade him to call muster. At least scout the location, find the source and the truth of this – find the missing girl. And you must tell me!”

Triqueta checked the bow at her saddleside and swung herself easily onto the palomino’s back. She had no rein: she rode the mare by knees alone.

Ress snorted. “Gods’ sakes, for the last time –”

“Listen! I said nothing of fears or figments or monsters.” Roderick let go the chearl’s soft nose and stepped back. “Only this: tell Larred Jade he has a threat on his border. Tell him a force rises against him. Tell him the Great Fayre has no defence. Tell him the biggest Gods-damned arrow you’ve ever seen made this boy’s wound. Do whatever it takes, Ress of the Banned. But don’t leave this boy’s teacher to die – and, by the Gods, tell me what you find!”

“And how do you suggest we do that?” Ress’s comment was barbed. “Or do you also believe in scrying?”

The little palomino mare scraped a forehoof on the cobbles, shook her mane and ears.

“Jade’s not a warrior,” Triq said. “His patrols secure his trade.”

“His trade will be the first target!” The Bard had a hand on the gate, but hadn’t opened it, not yet – he had one final bid to make. “You said your horse was spooked. What frightened her?”

Читать дальше