“Help him!”

The few remaining members of the Banned were moving, shouting.

“Triq!” Stool going over, one of the vets was shoving his way to the fore, around him, his mates were drunkenly swearing. Voices clamoured. “What the rhez?” “Who’s that ?” “Watch it, you sonofamare, that was my beer!”

Triqueta was folding under the weight.

“Ress! He’s out cold – pretty badly chewed up.”

The tide of questions rose again.

“Over here!” Roderick made a grab for the nearest rocklight, shadows leaped like figments through the room as he lifted it over a table. “Put him there, in the light. I’ll get you water.”

With a grunt, Triqueta hefted the boy onto the tabletop.

And stood back.

It was deep night, and the tavern’s staff had long since retired. In The Wanderer’s taproom, the Banned’s final die-hards had gathered close to raise old songs and leather tankards, but the soldiers had finally reeled away and the rest of the room was empty. Cursing rolled from a nearby figure, snoring on a bench.

The veteran Ress, tall and lean, his short beard shot with grey, studied the boy’s dirt-streaked face.

Triq’s hands clenched into fists at her sides. “He was conscious when I found him, just. His ankle’s busted – he’s a mess. Think you can fix him?”

“Think I can try.”

The remaining Banned had lowered voices and vessels.

As Roderick returned with water, Ress was cutting deftly through the boy’s shirt and breeches and leaning in close, examining cloth bindings in the tavern’s pooled rocklight.

Triqueta fidgeted, swiped a tankard from one of her cohorts and took a long swig.

Ress glanced at her, puzzled. “You treated him?”

“Fat chance!” She wiped her mouth on her sleeve.

“Oi, Triq!” A voice from the table. “Bit young for you?”

“Not funny.” She threatened them with the tankard, turned back to Ress. “Found him out towards the Monument. He’d made a crutch out of a javelin, Gods know how he got this far.”

“The Monument?” The Bard glanced at the doorway, an odd, formless shock prickling along his nerves. “That’s crazed.”

Triq had another mouthful of ale.

The rocklight showed the boy’s slim, pale chest was crusted in blood. His shirt, breeches and bindings were stuck to him. With calm, steady hands, Ress was soaking the fabric away from his skin.

“Tough kid,” he murmured.

“He spooked my mare,” Triqueta said. “Had a rhez of time getting him back here.”

The Banned round the table were muttering superstition and ribald defiance. A hand grabbed Triq’s wrist and, amidst laughter, the ale tankard went back to its owner.

“One thing at a time.” Under Ress’s gentle fingers, the blood-clotted fabric peeled away from the boy’s wound like a scab. The apothecary wheeshed through his teeth. “Whoever treated him knew what they were doing. Only reason he’s got this far. He’s been spitted. Ready for roasting. Straight through, front to back.”

No healer, the Bard could only stay out of the light and watch. The mention of the Monument had thrown him, and he found that he was trying to remember something, a figment that had long since faded into darkness and the Count of Time.

But Ress was studying the boy, neatly slicing off breeches and boots.

“The ankle – wouldn’t’ve been serious. If he’s walked on it –” he paused as if trying to encompass this information “– it’s splinters. Only made it because he kept his boots on. It’ll heal, but he’ll be crippled.” He rubbed one hand though his beard. “His hip – chips off the bone. It’s gone through at an angle – sitting on the horse has scrambled it badly. If it’s punctured his kidney... Gods, I don’t even know what could have made a hole like this.” He shrugged exasperation. “Anyone? Suggestions? Serious ones?”

Triq said, “Where do I know him from?”

“So many, you’ve forgotten?” One of her Banned cohorts made a foul gesture and she punched his ear without missing a breath. There were guffaws, like the releasing of tension. Understanding their need for humour, Roderick covered a brief grin.

But he moved the rocklight to study the boy.

The kid’s face was sunburned, freckled, streaked with tears, there was an old scar in his eyebrow. He had crazed, orange hair and several days’ growth of fluff on his chin. And yes, he was faintly familiar.

It teased him as though a breeze had chilled his skin. Silently, the Bard cursed the irony of his moniker – like the very world herself, his memory was flawed.

Then his eyes were pulled to the terrible hole in the boy’s hip.

And he found his hand over his mouth, his stomach knotting.

The wound was huge, as though a javelin had been driven through the boy’s flesh, but harder than any mortal hand could wield it. Around it, the skin was white, torn, crusted with old blood and fabric threads. Its edges were a vicious red and deep bruising had spread down the front of his hipbone. He could see the end of a piece of swollen, blood-black wood, splintered as though it’d been poorly snapped. “Spitted”, Ress had said. It was too fat for an arrow, too narrow for a spear – and it had gone through the boy’s body like he was thinly stretched hide.

The boy’s courage and resilience bereft him of words.

Where had he come from?

The air rippled again, his almost-recollection made him shudder with imagined cold.

But the boy was stirring.

Ress moved to his side, voice and hands gentle. Triq came close, too, standing beside Roderick. She smelled of sun and spice and fresh sweat.

“In the desert,” she said softly, “life’s precious – to be celebrated. Saving that life’s more precious still.”

The apothecary flicked a glance at her, raised a curious eyebrow. But she’d turned away and the boy was awake, moving, trying to talk.

At the table, there were ragged cheers. Leather tankards thumped together as they raised a toast to Ress’s skill.

His shaking hands wrapped around the neck of a waterskin, the boy was speaking.

“I made it – I really did it!” His breathing was ragged. “I feel like I’m dreaming, I just walked and I walked and it wasn’t really me and I never thought –”

“Easy.” Ress said softly. “You’ve got a lot to tell... it can wait for a minute. You’re hurt, lost a lot of blood –”

“I did good though, didn’t I? I did it right?”

“You did...?” Triq almost pounced on him, but Ress understood.

“You... treated yourself...?”

“This is The Wanderer.” His expression softened, staring in amazement at the taproom round him. His gaze came to rest on the Bard. “Amethea... she said... she’d eat her saddle and ride home bareback... She...” His jaw shook as he fought back a surge of tears.

“Shhhh.” Roderick laid a hand carefully on his shoulder. “We’ll take care of you now.”

“Wait.” The boy caught his arm. “I have to tell you. You’re the Bard. Maybe you need to know this more than anybody.”

And then he told his story.

* * *

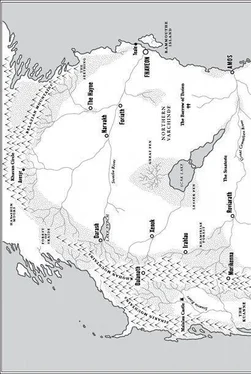

Like the cold, spiked spine of some vast and sleeping creature, the Kartiah Mountains curved a silent guard at the westernmost limit of the Grasslands. By tradition, they were the home of darkness, the element made manifest; sun and moons both sank to their daily deaths upon the bared stone peaks. Down their flanks, the last of the light was spilled like blood and there forests swelled and grew. In their bellies, metal lay quiescent, awaiting the tactile skill of the Kartian craftmasters.

From here came the first scattered springs of the Great Cemothen River, the plainlands’ central waterway that gathered its tributaries at Roviarath and then carved long leagues of meanders to the estuary and the dark sprawl of Amos.

Читать дальше