I started by setting three principles for reform. First, nothing would change for seniors or people near retirement. Second, I would seek to make Social Security solvent without raising payroll taxes, which had already expanded from about 2 percent to 12 percent. Third, younger workers should have the option of earning a better return by investing part of their Social Security taxes in a personal retirement account.

Personal retirement accounts would be new to Social Security, but most Americans were familiar with the concept. Like 401(k) accounts, they could be invested in a safe mix of stock and bond funds, which would grow over time and benefit from the power of compound interest. The accounts would be managed by reputable financial institutions charging low fees, and there would be prohibitions against withdrawing the money before retirement. Even at a conservative rate of return of 3 percent, an account holder’s money would double every twenty-four years. By contrast, Social Security’s return of 1.2 percent would take sixty years to double. Unlike Social Security benefits, personal retirement accounts would be an asset owned by individual workers, not the government, and could be passed from one generation to the next.

In early 2005, I sat down with Republican congressional leaders to talk through our legislative strategy. I told them modernizing Social Security would be my first priority. The reaction was lukewarm, at best.

“Mr. President,” one leader said, “this is not a popular issue. Taking on Social Security will cost us seats.”

“No,” I shot back, “failing to tackle this issue will cost us seats.”

It was clear they were thinking about the two-year election cycle of Capitol Hill. I was thinking about the responsibility of a president to lead on issues affecting the long-term prospects of the country. I reminded them that I had campaigned on this issue twice, and the problem was only going to get worse. By solving it, we would do the country a great service. And ultimately, good policy makes for good politics.

“If you lead, we’ll be behind you,” one House leader said, “but we’ll be way behind you.”

The meeting with congressional Republicans showed what an uphill climb I had on Social Security. I decided to press ahead anyway. When I looked back on my presidency, I didn’t want to say I had dodged a big issue.

“Social Security was a great moral success of the twentieth century, and we must honor its great purposes in this new century,” I said in my 2005 State of the Union address. “The system, however, on its current path, is headed toward bankruptcy. And so we must join together to strengthen and save Social Security.”

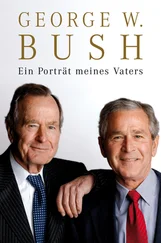

With Mother campaigning for Social Secuirty reform. White House/Paul Morse

The next day, I embarked on a series of trips to raise awareness about Social Security’s problems and rally the American people to insist on change. I gave speeches, convened town halls, and even held an event with my favorite Social Security beneficiary, Mother. “I’m here because I’m worried about our seventeen grandchildren, and so is my husband,” she said. “They will get no Social Security.”

One of my most memorable trips was to a Nissan auto-manufacturing plant in Canton, Mississippi. Many in the audience were African American workers. I asked how many had money invested in a 401(k). Almost every hand in the room shot up. I loved the idea of people who had not traditionally owned assets having a nest egg they could call their own. I also thought about how much more was possible. Social Security was especially unfair to African Americans. Because their life expectancy was shorter, black workers who spent a lifetime paying into Social Security received an average of $21,000 less in benefits than whites of comparable income levels. Personal accounts, which could be passed along to the next generation, would go a long way toward reducing that disparity.

On April 28, I called a primetime press conference to lay out a specific proposal. The plan I embraced was the brainchild of a Democrat, Robert Pozen. His proposal, known as progressive indexing, set benefits to grow fastest for the poorest Americans and slowest for the wealthiest. There would be a sliding scale for everyone in between. By changing the benefit growth formula, the plan would wipe out the vast majority of the Social Security shortfall. In addition, all Americans would have the opportunity to earn higher returns through personal retirement accounts.

I hoped both sides would embrace the proposal. Republicans would be pleased that we could vastly improve the budget outlook without raising taxes. Democrats should have been pleased by a reform that saved Social Security, the crown jewel of the New Deal, by offering the greatest benefits to the poor, minorities, and the working class—the constituents they claimed to represent.

My legislative team***** pushed the plan hard, but it received virtually no support. Democratic leaders in the House and Senate alleged I wanted to “privatize” Social Security. That was obviously poll-tested language designed to scare people. It wasn’t true. My plan saved Social Security, modernized Social Security, and gave Americans the opportunity to own a piece of their Social Security. It did not privatize Social Security. I sensed there was something broader behind the Democrats’ opposition. National Economic Council Director Al Hubbard told me about a meeting he’d had on Capitol Hill. “I’d like to be helpful on this,” one senior Democratic senator told him, “but our leaders have made clear we’re not supposed to cooperate.”

The rigid Democratic opposition on Social Security came in stark contrast to the bipartisanship I had been able to forge on No Child Left Behind and during my years in Texas. I was disappointed by the change, and I’ve often thought about why it occurred. I think there were some on the other side of the aisle who never got over the 2000 election and were determined not to cooperate with me. Others resented that I had campaigned against Democratic incumbents in 2002 and 2004, helping Republican candidates unseat Democratic icons like Senator Max Cleland of Georgia and Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle.

No doubt I bear some of the responsibility as well. I don’t regret campaigning for fellow Republicans. I had always made clear that I intended to increase our party’s strength in Washington. While I was willing to fine-tune legislation in response to Democratic concerns, I would not compromise my principles, which was what some seemed to expect in return for cooperation. On Social Security, I may have misread the electoral mandate by pushing for an issue on which there had been little bipartisan agreement in the first place. Whatever the cause, the breakdown in bipartisanship was bad for my administration and bad for the country, too.

With no Democrats on board, I needed strong Republican backing to get a Social Security bill through Congress. I didn’t have it. Many younger Republicans, such as Congressman Paul Ryan of Wisconsin, supported reform. But few in Congress were willing to address such a contentious issue.

The collapse of Social Security reform is one of the greatest disappointments of my presidency. Despite our efforts, the government ended up doing exactly what I had warned against: We kicked the problem down the road to the next generation. In retrospect, I’m not sure what I could have done differently.

I made the case for reform as widely and persuasively as I could. I tried hard to reach across the aisle and made a Democratic economist’s proposal the crux of my plan. The failure of Social Security reform shows the limits of the president’s power. If Congress is determined not to act, there is only so much a president can do.

Читать дальше