Nothing gave me more confidence than our troops. Thanks to them, most of the senior members of Saddam’s regime had been captured or killed by the end of 2003. In July, we got an intelligence tip that Saddam’s two sons were in the Mosul area of northern Iraq. Joined by Special Forces, troops from the 101st Airborne under the command of General David Petraeus laid siege to the building where Hussein’s sons, Uday and Qusay, were hiding. After a six-hour firefight, both were dead. We later received intelligence that Saddam had ordered the killing of Barbara and Jenna in return for the death of his sons.

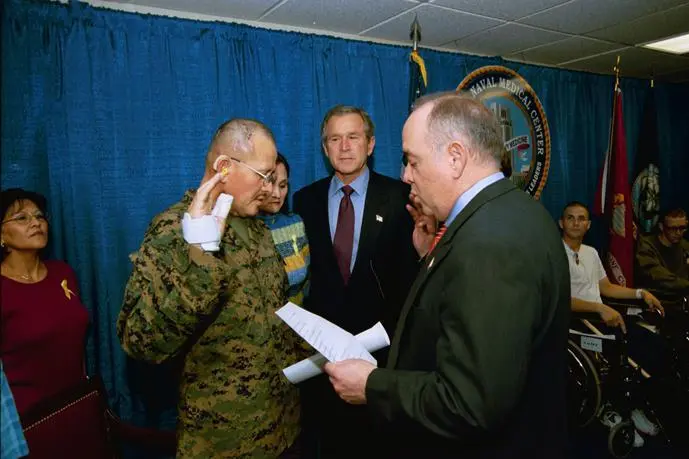

Two days after the fall of Baghdad, Laura and I visited Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington and the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda. We met with almost a hundred wounded service members and their families. Some were from Afghanistan; many were from Iraq. It was a heart-wrenching experience to look into a hospital bed and see the consequences of sending Americans into combat. One comfort was that I knew they would receive superb medical care from the skilled and compassionate professionals of the military health-care system.

Visiting the wounded was both the toughest and most inspiring part of my job. Here, with Sergeant Patrick Hagood at Walter Reed Army Medical Center. White House/Paul Morse

At Walter Reed, I met a member of the Delta Team, one of our elite Special Forces units. For classification reasons, I cannot give his name. He had lost the lower half of his leg. “I appreciate your service,” I said as I shook his hand. “I’m sorry you got hurt.”

“Don’t feel sorry for me, Mr. President,” he replied. “Just get me another leg so I can go back in.”

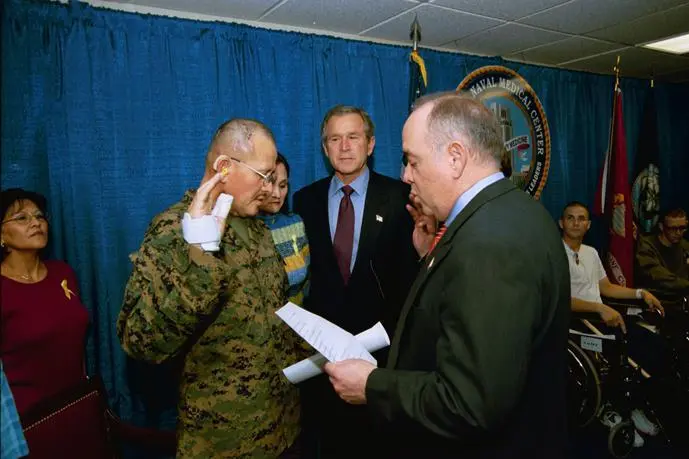

At the National Naval Medical Center, I met forty-two-year-old Marine Master Gunnery Sergeant Guadalupe Denogean. He had been wounded a few weeks earlier, when a rocket-propelled grenade struck his vehicle. The explosion blew off part of his skull and his right hand; shrapnel penetrated his upper back and legs, and his eardrums burst.

When asked if he had any requests, Guadalupe said he had two. He asked for a promotion for the corporal who had saved his life. And he wanted to become an American citizen. After 9/11, I had issued an executive order making all foreign nationals serving in the military eligible for immediate citizenship.

Guadalupe had come to the United States from Mexico as a boy. He picked fruit to help his family make a living until he joined the Marines at age seventeen. After serving for twenty-five years—and deploying for two wars with Iraq—he wanted the flag on his uniform to be his own. That day in the hospital, Laura and I attended his naturalization ceremony, conducted by Director Eduardo Aguirre of the Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services. Guadalupe raised his right hand, covered in bandages, and swore the oath of citizenship.

Witnessing Master Gunnery Sergeant Guadalupe Denogean become an an American citizen. White House/Eric Draper

A few moments later, he was followed by Marine Lance Corporal O.J. Santamaria, a native of the Philippines. He was twenty-one years old and had suffered a serious wound in Iraq. He was hooked up to an intravenous blood transfusion. About halfway through the ceremony, he broke down in tears. He powered through to the end of the oath. I was proud to respond, “My fellow American.”

In the fall of 2003, Andy Card came to me with an idea. Was I interested in making a trip to Iraq to thank the troops? You bet I was.

The risk was high. But Deputy Chief of Staff Joe Hagin, working with the Secret Service and White House Military Office, came up with a way to pull it off. The week of Thanksgiving, I would travel to Crawford and tell the press I was staying for the full holiday. Then, on Wednesday night, I would slip out of the ranch and fly to Baghdad.

I told Laura several weeks ahead of the trip. She was reassured when I told her we would abort the trip if news of it leaked. I told Barbara and Jenna about thirty minutes before I left. “I’m scared, Dad,” Barbara said. “Be safe. Come home.”

Condi and I climbed into an unmarked Suburban, our baseball caps pulled low, and headed for the airport. To maintain secrecy, there was no motorcade. I had nearly forgotten what a traffic jam felt like, but riding on I-35 the day before Thanksgiving brought the memories back. We crept along, passing an occasional car full of counterassault agents, and made it to Air Force One on schedule. Timeliness was important. We needed to land as the sun was setting in Baghdad.

We flew from Texas to Andrews Air Force Base, where we switched to the twin version of Air Force One and took off for Iraq. The plane carried a skeleton crew of staff, military and Secret Service personnel, and a press contingent sworn to secrecy. I slept little on the ten-and-a-half-hour flight. As we neared Baghdad, I showered, shaved, and headed to the cockpit to watch the landing. Colonel Mark Tillman manned the controls. I trusted him completely. As Laura always put it, “That Mark can sure land this plane.”

Sitting in the cockpit of Air Force One on the approach to Baghdad. White House/Tina Hager

With the sun dropping on the horizon, I could make out the minarets of the Baghdad skyline. The city seemed so serene from above. But we were concerned about surface-to-air missiles on the ground. While Joe Hagin assured us the military had cleared a wide perimeter around Baghdad International Airport, the mood aboard the plane was anxious. As we descended in a corkscrew pattern with the shades drawn, some staffers joined together in a prayer session. At the last moment, Colonel Tillman leveled out the plane and kissed the runway, no sweat.

Waiting for me at the airport were Jerry Bremer and General Ricardo Sanchez, the senior ground commander in Iraq. “Welcome to a free Iraq,” Jerry said.

We went to the mess hall, where six hundred troops had gathered for a Thanksgiving meal. Jerry was supposed to be the guest of honor. He told the troops he had a holiday message from the president. “Let’s see if we’ve got anybody more senior here …,” he said.

That was my cue. I walked out from behind a curtain and onto the stage of the packed hall. Many of the stunned troops hesitated for a split second, then let out deafening whoops and hooahs. Some had tears running down their faces. I was swept up by the emotion. These were the souls who just eight months earlier had liberated Iraq on my orders. Many had seen combat. Some had seen friends perish. I took a deep breath and said, “I bring a message on behalf of America. We thank you for your service, we’re proud of you, and America stands solidly behind you.”

After the speech, I had dinner with the troops and moved to a side room to meet with four members of the Governing Council, the mayor of Baghdad, and members of the city council. One woman, the director of a maternity hospital, told me how women had more opportunities now than they had ever dreamed about under Saddam. I knew Iraq still faced big problems, but the trip reinforced my faith that they could be overcome.

The most dangerous part left was the takeoff from Baghdad. We were told to keep all lights out and maintain total telephone silence until we hit ten thousand feet. I was still on an emotional high. But the exhilaration of the moment was replaced by an eerie feeling of uncertainty as we blasted off the ground and climbed silently through the night.

Читать дальше