“It’s a slam dunk,” he said.

I believed him. I had been receiving intelligence briefings on Iraq for nearly two years. The conclusion that Saddam had WMD was nearly a universal consensus. My predecessor believed it. Republicans and Democrats on Capitol Hill believed it. Intelligence agencies in Germany, France, Great Britain, Russia, China, and Egypt believed it. As the German ambassador to the United States, not a supporter of war, later put it, “I think all of our governments believe that Iraq has produced weapons of mass destruction and that we have to assume that they still have … weapons of mass destruction.” If anything, we worried that the CIA was underestimating Saddam, as it had before the Gulf War.

In retrospect, of course, we all should have pushed harder on the intelligence and revisited our assumptions. But at the time, the evidence and the logic pointed in the other direction. If Saddam doesn’t actually have WMD , I asked myself, why on earth would he subject himself to a war he will almost certainly lose?

Every Christmas during my presidency, Laura and I invited our extended family to join us at Camp David. We were happy to continue the tradition started by Mother and Dad. We cherished the opportunity to relax with them, Laura’s mom, Barbara and Jenna, and my brothers and sister and their families. We loved to watch the children’s pageant at the Camp David chapel and to sing carols with military personnel and their families. One of the highlights was an annual Pink Elephant gift exchange, in which my teenage nieces and nephews were not above pilfering the latest iPod or other coveted item from the president of the United States. In later years, we started a tradition of making donations in another family member’s name. Jeb and Doro donated books to the library aboard the USS George H.W. Bush . Marvin and his wife, Margaret, donated a communion chalice to the Camp David chapel on behalf of Laura and me. We gave a gift to the Dorothy Walker Bush Pavilion at the Southern Maine Medical Center in Mother and Dad’s name.

The Christmas pageant at Camp David's Evergreen Chapel, one of our favorite holiday traditions. White House/Eric Draper

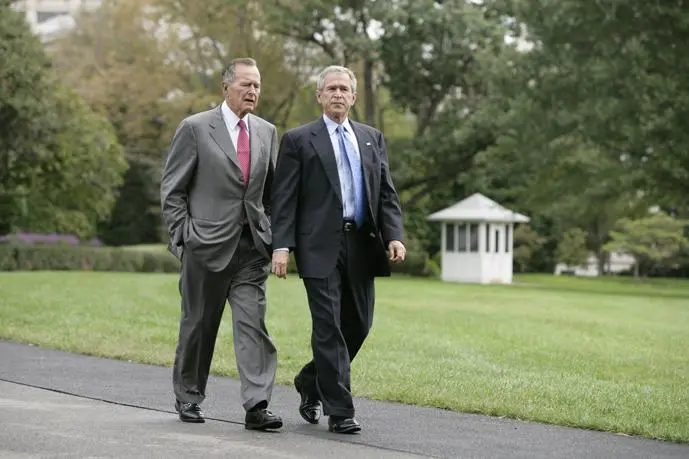

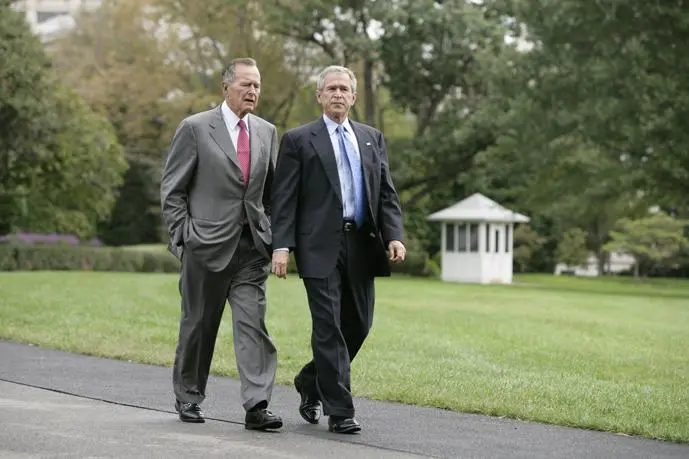

Amid the Christmas celebrations in 2002, Dad and I talked about Iraq. For the most part, I didn’t seek Dad’s advice on major issues. He and I both understood that I had access to more and better information than he did. Most of our conversations were for me to reassure him that I was doing fine and for him to express his confidence and love.

Iraq was one issue where I wanted to know what he thought. I told Dad I was praying we could deal with Saddam peacefully but was preparing for the alternative. I walked him through the diplomatic strategy—the solid support from Blair, Howard, and Aznar; the uncertainty with Chirac and Schroeder; and my efforts to rally the Saudis, Jordanians, Turks, and others in the Middle East.

He shared my hope that diplomacy would succeed. “You know how tough war is, son, and you’ve got to try everything you can to avoid war,” he said. “But if the man won’t comply, you don’t have any other choice.”

I sought Dad's advice on Iraq. White House/Eric Draper

Shortly after New Year’s, I sent Barbara and Jenna a letter at college. “I am working hard to keep the peace and avoid a war,” I wrote. “I pray that the man in Iraq will disarm in a peaceful way. We are putting pressure on him to do just that and much of the world is with us.”

As 2003 began, it became increasingly clear that my prayer would not be answered. On January 27, Hans Blix gave a formal report to the United Nations. His inspections team had discovered warheads that Saddam had failed to declare or destroy, indications of the highly toxic VX nerve agent, and precursor chemicals for mustard gas. In addition, the Iraqi government was defying the inspections process. The regime had violated Resolution 1441 by blocking U-2 flights and hiding three thousand documents in the home of an Iraqi nuclear official. “Iraq appears not to have come to a genuine acceptance, not even today, of the disarmament that was demanded of it,” Blix said.

I could see what was happening: Saddam was trying to shift the burden of proof from himself to us. I reminded our partners that the UN resolution clearly stated that it was Saddam’s responsibility to comply. As Mohamed ElBaradei, director of the International Atomic Energy Agency, explained in late January, “The ball is entirely in Iraq’s court. … Iraq now has to prove that it is innocent. … They need to go out of their way to prove through whatever possible means that they have no weapons of mass destruction.”

In late January, Tony Blair came to Washington for a strategy session. We agreed that Saddam had violated UN Security Council Resolution 1441 by submitting a false declaration. We had ample justification to enforce the “serious consequences.” But Tony wanted to go back to the UN for a second resolution clarifying that Iraq had “failed to take the final opportunity afforded to it.”

“It’s not that we need it,” Tony said. “A second resolution gives us military and political protection.”

I dreaded the thought of plunging back into the UN. Dick, Don, and Condi were opposed. Colin told me that we didn’t need another resolution and probably couldn’t get one. But if Tony wanted a second resolution, we would try. “As I see it, the issue of the second resolution is how best to help our friends,” I said.

The best way to get a second resolution was to lay out the evidence against Saddam. I asked Colin to make the presentation to the UN. He had credibility as a highly respected diplomat known to be reluctant about the possibility of war. I knew he would do a thorough, careful job. In early February, Colin spent four days and four nights at the CIA personally reviewing the intelligence to ensure he was comfortable with every word in his speech. On February 5, he took the microphone at the Security Council.

“The facts on Iraq’s behavior,” he said, “demonstrate that Saddam Hussein and his regime have made no effort—no effort—to disarm as required by the international community. Indeed, the facts and Iraq’s behavior show that Saddam Hussein and his regime are concealing their efforts to produce more weapons of mass destruction.”

Colin’s presentation was exhaustive, eloquent, and persuasive. Coming against the backdrop of Saddam’s defiance of the weapons inspectors, it had a profound impact on the public debate. Later, many of the assertions in Colin’s speech would prove inaccurate. But at the time, his words reflected the considered judgment of intelligence agencies at home and around the world.

“We are both moral men,” Jacques Chirac told me after Colin’s speech. “But in this case, we see morality differently.” I replied politely, but I thought to myself: If a dictator who tortures and gasses his people is not immoral, then who is?

Three days later, Chirac stepped in front of the cameras and said, “Nothing today justifies war.” He, Gerhard Schroeder, and Vladimir Putin issued a joint statement of opposition. All three of them sat on the Security Council. The odds of a second resolution looked bleak.

Tony urged that we forge ahead. “The stakes are now much higher,” he wrote to me on February 19. “It is apparent to me from the EU summit that France wants to make this a crucial test: Is Europe America’s partner or competitor?” He reminded me we had support from a strong European coalition, including Spain, Italy, Denmark, the Netherlands, Portugal, and all of Eastern Europe. In a recent NATO vote, fifteen members of the alliance had supported military action in Iraq, with only Belgium and Luxembourg standing with Germany and France. Portuguese Prime Minister José Barroso spoke for many European leaders when he asked, incredulously, “We are faced with the choice of America or Iraq, and we’re going to pick Iraq?”

Читать дальше