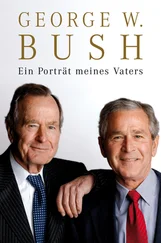

On the surface, it seemed we were making progress. But trouble lurked underneath. In June 2005, a four-man Navy SEAL team operating high in the mountains was ambushed by the Taliban. The team leader, Lieutenant Michael Murphy, moved into an exposed position to call in help for his three fellow wounded SEALs. He stayed on the line long enough to relay his teammates’ location before suffering fatal wounds. When a Special Forces chopper arrived to extract the SEALs, Taliban fighters shot it down. Nineteen Americans were killed, making it the deadliest day of the war in Afghanistan and the worst for the SEALs since World War II. One SEAL, Petty Officer First Class Marcus Luttrell, lived to tell the story in his riveting book, Lone Survivor .

Two years later, I presented the Medal of Honor to Lieutenant Michael Murphy’s parents in the East Room of the White House. We talked about their son, a talented athlete and honors graduate of Penn State whose one brush with trouble came when he intervened in a schoolyard fight to protect a disabled child. In our meeting before the ceremony, they gave me a gold dog tag with Mike’s name, photo, and rank engraved on it. I put it on under my shirt and wore it during the ceremony.

Presenting Dan and Maureen Murphy with the Medal of Honor earned by their son, Navy Lieutenant Michael Murphy. White House/Joyce Boghosian

As the military aide read the Medal of Honor citation, I looked into the audience. I saw a group of Navy SEALs in their dress blues. These battle-hardened men had tears streaming down their cheeks. As I later told Daniel and Maureen Murphy, I gained strength from having a reminder of Mike next to my heart.

The devastating attack on the SEALs was a harbinger of trouble to come. In 2005 and 2006, Taliban militants killed road-building crews, burned down schools, and murdered teachers in provinces near the Pakistan border. In September 2006, a Taliban suicide bomber assassinated the governor of Paktia Province near his office in Gardez. The next day, another suicide bomber struck the governor’s funeral, killing six mourners.

My CIA and military briefings included increasingly dire reports about Taliban influence. The problem was crystallized by a series of color-coded maps I saw in November 2006. The darker the shading, the more attacks had occurred in that part of Afghanistan. The 2004 map was lightly shaded. The 2005 map had darker areas in the southern and eastern parts of the country. By 2006, the entire southeastern quadrant was black. In just one year, the number of remotely detonated bombs had doubled. The number of armed attacks had tripled. The number of suicide bombings had more than quadrupled.

It was clear we needed to adjust our strategy. The multilateral approach to rebuilding, hailed by so many in the international community, was failing. There was little coordination between countries, and no one devoted enough resources to the effort. The German initiative to build the national police force had fallen short. The Italian mission to reform the justice system had failed. The British-led counternarcotics campaign showed results in some areas, but drug production had boomed in fertile southern provinces like Helmand. The Afghan National Army that America trained had improved, but in an attempt to keep the Afghan government from taking on an unsustainable expense, we had kept the army too small.

The multilateral military mission proved a disappointment as well. Every member of NATO had sent troops to Afghanistan. So had more than a dozen other countries. But many parliaments imposed heavy restrictions—known as national caveats—on what their troops were permitted to do. Some were not allowed to patrol at night. Others could not engage in combat. The result was a disorganized and ineffective force, with troops fighting by different rules and many not fighting at all.

Failures in the Afghan government contributed to the problem. While I liked and respected President Karzai, there was too much corruption. Warlords pocketed large amounts of customs revenue that should have gone to Kabul. Others took a cut of the profits from the drug trade. The result was that Afghans lost faith in their government. With nowhere else to turn, many Afghans relied on the Taliban and ruthless extremist commanders like Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and Jalaluddin Haqqani. A CIA report quoted one Afghan as saying, “I don’t care who is in power, as long as they bring security. Security is all that matters.”

The stakes were too high to let Afghanistan fall back into the hands of the extremists. I decided that America had to take on more of the responsibility, even though we were about to undertake a major new commitment in Iraq as well.

“Damn it, we can do more than one thing at a time,” I told the national security team. “We cannot lose in Afghanistan.”

In the fall of 2006, I ordered a troop increase that would boost our force levels from twenty-one thousand to thirty-one thousand over the next two years. I called the 50 percent increase a “silent surge.”** To help the Afghan government extend its reach and effectiveness, we more than doubled funding for reconstruction. We increased the number of Provincial Reconstruction Teams, which brought together military personnel and civilian experts to ensure that security gains were translated into meaningful improvements in everyday life. We also increased the size of the Afghan National Army, expanded our counternarcotics effort, improved intelligence efforts along the Pakistan border, and sent civilian experts from the U.S. government to help Afghan ministries strengthen their capacity and reduce corruption.

I urged our NATO allies to match our commitment by dropping caveats on their troops and adding more forces. Several leaders responded, including Stephen Harper of Canada, Anders Fogh Rasmussen of Denmark, and Nicolas Sarkozy of France. The British and Canadians fought especially bravely and suffered significant casualties. America was fortunate to have them at our side, and we honor their sacrifice as our own.

Other leaders told me bluntly that their parliaments would never go along. It was maddening. Afghanistan was supposed to be a war the world had agreed was necessary and just. And yet many countries were sending troops so heavily restricted that our generals complained they just took up space. NATO had turned into a two-tiered alliance, with some countries willing to fight and many not.

The adjustments in our strategy improved our ability to take on the insurgents. Yet the violence continued. The primary cause of the trouble did not originate in Afghanistan or, as some suggested, in Iraq. It came from Pakistan.

For most of my presidency, Pakistan was led by President Pervez Musharraf. I admired his decision to side with America after 9/11. He held parliamentary elections in 2002, which his party won, and spoke about “enlightened moderation” as an alternative to Islamic extremism. He took serious risks to battle al Qaeda. Terrorists tried to assassinate him at least four times.

With Pervez Musharraf. White House/Paul Morse

In the months after we liberated Afghanistan, I told Musharraf I was troubled by reports of al Qaeda and Taliban forces fleeing into the loosely governed, tribal provinces of Pakistan—an area often compared to the Wild West. “I’d be more than willing to send our Special Forces across the border to clear out the areas,” I said.

Читать дальше