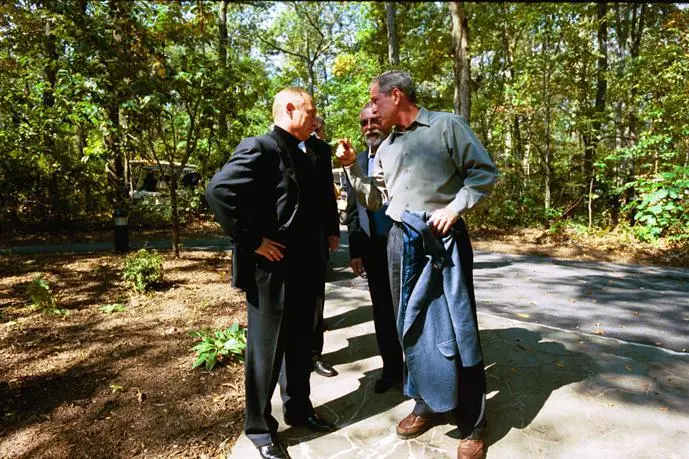

At Camp David with Vladimir Putin. White House/Eric Draper

The summit with Putin started with a small meeting—just Vladimir and me, our national security advisers, and the interpreters. He seemed a little tense. He opened by speaking from a stack of note cards. The first topic was the Soviet-era debt of the Russian Federation.

After a few minutes, I interrupted his presentation with a question: “Is it true your mother gave you a cross that you had blessed in Jerusalem?”

A look of shock washed over Putin’s face as Peter, the interpreter, delivered the line in Russian. I explained that the story had caught my attention in some background reading—I didn’t tell him it was an intelligence briefing—and I was curious to learn more. Putin recovered quickly and told the story. His face and his voice softened as he explained that he had hung the cross in his dacha, which subsequently caught on fire. When the firefighters arrived, he told them all he cared about was the cross. He dramatically re-created the moment when a worker unfolded his hand and revealed the cross. It was, he said, “as if it was meant to be.”

“Vladimir,” I said, “that is the story of the cross. Things are meant to be.” I felt the tension drain from the meeting room.

After the meeting, a reporter asked if Putin was “a man that Americans can trust.” I said yes. I thought of the emotion in Vladimir’s voice when he shared the story of the cross. “I looked the man in the eye,” I said, “… I was able to get a sense of his soul.” In the years ahead, Putin would give me reasons to revise my opinion.

Three months after our meeting in Slovenia, Putin was the first foreign leader to call the White House on September 11. He couldn’t reach me on Air Force One, so Condi spoke to him from the PEOC. He assured her that Russia would not increase its military readiness in response to our move to DefCon Three, as the Soviet Union would have done automatically during the Cold War. When I talked to Vladimir the next day, he told me he had signed a decree declaring a minute of silence to show solidarity with the United States. He ended by saying, “Good will triumph over evil. I want you to know that in this struggle, we will stand together.”

On September 22, I called Putin from Camp David. In a long Saturday-morning conversation, he agreed to open Russian airspace to American military planes and use his influence with the former Soviet republics to help get our troops into Afghanistan. I suspected he would be worried about Russia being encircled, but he was more concerned about the terrorist problem in his neighborhood. He even ordered Russian generals to brief their American counterparts on their experience during their Afghanistan invasion in the 1980s.

It was an amazing conversation. I told Vladimir I appreciated his willingness to move beyond the suspicions of the past. Before long, we had our agreements with the former Soviet republics.

In late September, George Tenet reported that the first of the CIA teams had entered Afghanistan and linked up with the Northern Alliance. Tommy Franks told me he would be ready to deploy our Special Forces soon. I threw out a question to the team that had been on my mind: “So who’s going to run the country?”

There was silence.

I wanted to make sure the team had thought through the postwar strategy. I felt strongly that the Afghan people should be able to select their new leader. They had suffered too much—and the American people were risking too much—to let the country slide back into tyranny. I asked Colin to work on a plan for a transition to democracy.

On Friday, October 5, General Dick Myers told me the military was ready to launch. I was ready, too. We had given the Taliban more than two weeks to respond to the ultimatum I had delivered. The Taliban had not met any of our demands. Their time was up.

Don Rumsfeld was on his way back from the Middle East and Central Asia, where he had finalized several important basing agreements. I waited for him to return before I gave the official order. On Saturday morning, October 6, I spoke to Don and Dick Myers by secure video-conference from Camp David. I asked one last time if they had everything they needed. They did.

“Go,” I said. “This is the right thing to do.”

I knew in my heart that striking al Qaeda, removing the Taliban, and liberating the suffering people of Afghanistan was necessary and just. But I worried about all that could go wrong. The military planners had laid out the risks: mass starvation, an outbreak of civil war, the collapse of the Pakistani government, an uprising by Muslims around the world, and the one I feared most—a retaliatory attack on the American homeland.

When I boarded Marine One the next morning to return to Washington, Laura and a few key advisers knew I had given the order, but virtually no one else did. To preserve the secrecy of the operation, I went ahead with my previously announced schedule, which included attending a ceremony at the National Fallen Firefighters Memorial in Emmitsburg, Maryland. I spoke about the 343 New York City firefighters who had given their lives on 9/11, by far the worst day in the history of American firefighting. The casualties ranged from the chief of the department, Pete Ganci, to young recruits in their first months on the job.

The memorial was a vivid reminder of why America would soon be in the fight. Our military understood, too. Seven thousand miles away, the first bombs fell. On several of them, our troops had painted the letters FDNY .

The first reports out of Afghanistan were positive. In two hours of aerial bombardment, we and our British allies had wiped out the Taliban’s meager air defense system and several known al Qaeda training camps. Behind the bombs, we dropped more than thirty-seven thousand rations of food and relief supplies for the Afghan people, the fastest delivery of humanitarian aid in the history of warfare.

After several days, we ran into a problem. The air campaign had destroyed most of the Taliban and al Qaeda infrastructure. But we were having trouble inserting our Special Forces. They were grounded at a former Soviet air base in Uzbekistan, separated from their landing zone in Afghanistan by fifteen-thousand-foot-high mountains, freezing temperatures, and blinding snowstorms.

I pressed for action. Don and Tommy assured me they were moving as fast as possible. But as the days passed, I became more and more frustrated. Our response looked too much like the impotent air war America had waged in the past. I worried we were sending the wrong message to the enemy and to the American people. Tommy Franks later called those days a period “from hell.” I felt the same way.

Twelve days after I announced the start of the war, the first of the Special Forces teams finally touched down. In the north, our forces linked up with the CIA and Northern Alliance fighters. In the south, a small team of Special Forces raided Taliban leader Mullah Omar’s headquarters in Kandahar.

Months later, I visited Fort Bragg in North Carolina, where I met members of the Special Forces team that had led the raid. They gave me a brick from the remnants of Mullah Omar’s compound. I kept it in the private study next to the Oval Office as a reminder that we were fighting this war with boots on the ground—and that the Americans in those boots were courageous and skilled.

Читать дальше