We started the Cabinet meeting with a prayer. I asked Don Rumsfeld to lead it. He offered moving words about the victims of the attacks and asked for the “patience to measure our lust for action.” The moment of silence after the prayer gave me time to collect my emotions. I thought about the speech I would soon give at the National Cathedral. Apparently Colin Powell did, too. The secretary of state slipped me a note.

“Dear Mr. President,” he wrote. “When I have to give a speech like this, I avoid those words that I know will cause me to well up, such as Mom and Pop.” It was a thoughtful gesture. Colin had seen combat; he knew the powerful emotions we were all feeling and wanted to comfort me. As I began the meeting, I held up the note and joked, “Let me tell you what the secretary of state just told me. … ‘Dear Mr. President, Don’t break down!’ ”

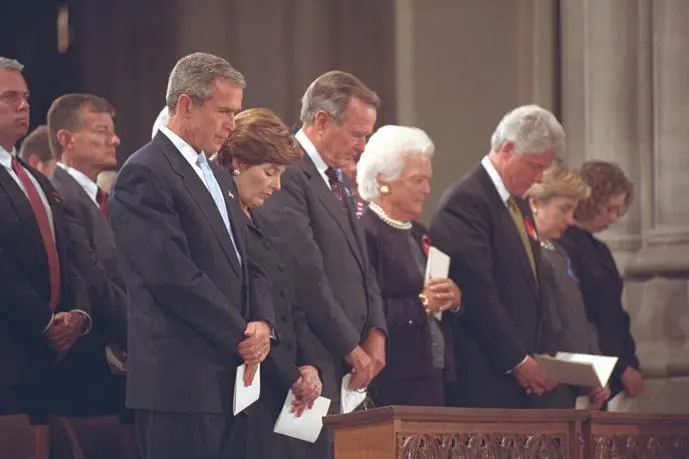

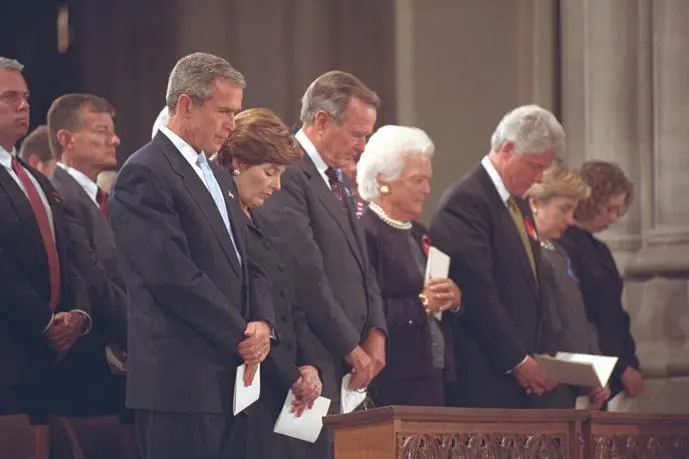

The National Cathedral is an awesome structure, with 102-foot ceilings, elegant buttresses, and sparkling stained glass. On September 14 the pews were filled to capacity. Former Presidents Ford, Carter, Bush, and Clinton were there with their wives. So was almost every member of Congress, the whole Cabinet, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the justices of the Supreme Court, the diplomatic corps, and families of the victims. One person not there was Dick Cheney. He was at Camp David to ensure the continuity of government, a reminder of the ongoing threat.

At the National Cathedral. White House/Eric Draper

I had asked Laura and Karen Hughes to design the program, and they did a fine job. The speakers included religious leaders of many faiths: Imam Muzammil Siddiqi of the Islamic Society of North America, Rabbi Joshua Haberman, Billy Graham, Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, and Kirbyjon Caldwell. Near the end of the service, my turn came. As I climbed the steps to the lectern, I whispered a prayer: “Lord, let your light shine through me.”

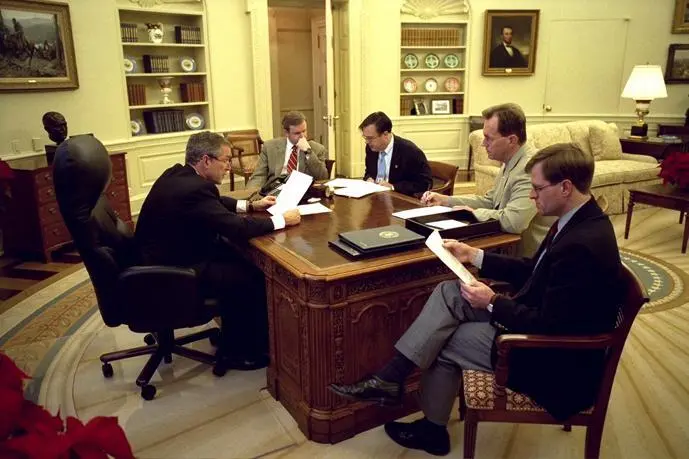

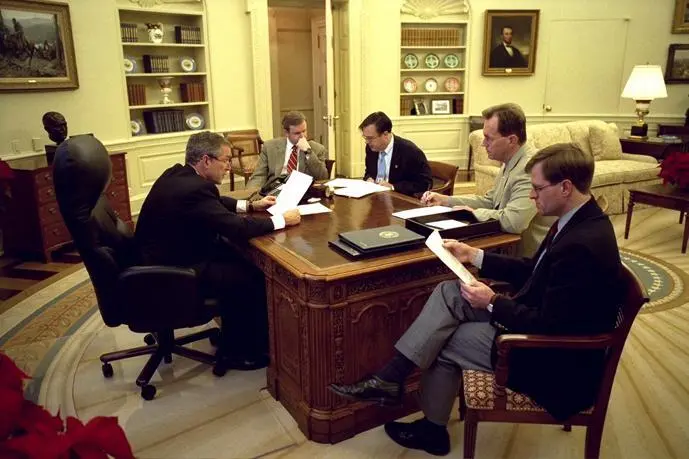

The speech at the cathedral was the most important of my young presidency. I had told my speechwriters—Mike Gerson, John McConnell, and Matthew Scully—that I wanted to accomplish three objectives: mourn the loss of life, remind people there was a loving God, and make clear that those who attacked our nation would face justice.

With my speechwriters ( from left ) Dan Bartlett, Mike Gerson, Matthew Scully, and John McConnell. White House/Eric Draper

“We are here in the middle hour of our grief,” I began. “So many have suffered so great a loss, and today we express our nation’s sorrow. We come before God to pray for the missing and the dead, and for those who love them. … To the children and parents and spouses and families and friends of the lost, we offer the deepest sympathy of the nation. And I assure you, you are not alone.”

I scanned the crowd. Three soldiers sitting to my right had tears cascading down their faces. So did my lead advance woman, Charity Wallace. I was determined not to fall prey to the contagion of crying. There was one place I dared not look: the pew where Mother, Dad, and Laura were seated. I continued: Just three days removed from these events, Americans do not yet have the distance of history. But our responsibility to history is already clear: to answer these attacks and rid the world of evil. War has been waged against us by stealth and deceit and murder. This nation is peaceful, but fierce when stirred to anger. This conflict was begun on the timing and terms of others. It will end in a way, and at an hour, of our choosing.…God’s signs are not always the ones we look for. We learn in tragedy that His purposes are not always our own. Yet the prayers of private suffering, whether in our homes or in this great cathedral, are known and heard, and understood. … This world He created is of moral design. Grief and tragedy and hatred are only for a time. Goodness, remembrance, and love have no end. And the Lord of life holds all who die, and all who mourn.

As I took my seat next to Laura, Dad reached over and gently squeezed my arm. Some have said the moment marked a symbolic passing of the torch from one generation to another. I saw it as the reassuring touch of a father who knew the challenges of war. I drew strength from his example and his love. I needed that strength for the next stage of the journey: the visit to the point of attack, lower Manhattan.

The flight north was quiet. I had asked Kirbyjon Caldwell to make the trip with me. I had seen the footage of New York on television, and I knew the devastation was overwhelming. It was comforting to have a friend and a man of faith by my side.

Governor Pataki and Mayor Giuliani greeted me at McGuire Air Force Base in New Jersey. They looked spent. The governor had been working tirelessly since Tuesday morning, allocating state resources and rallying the troops under his command. And rarely had a man met his moment in history more naturally than Rudy Giuliani did on September 11. He was defiant at the right times, sorrowful at the right times, and in command the entire time.

Huddling with Rudy Giuliani ( left ) and George Pataki at McGuire Air Force Base. White House/Paul Morse

I boarded the chopper with George and Rudy. On the flight into the city, the Marine pilots flew over Ground Zero. My mind went back to the helicopter flight on the evening of September 11. The Pentagon had been wounded, but not destroyed. That was not the case with the Twin Towers. They were gone. There was nothing left but a pile of rubble. The devastation was shocking and total.

The view from the air was nothing compared to what I saw on the ground. George, Rudy, and I piled into a Suburban. We had just started the drive to the disaster site when something on the side of the road caught my eye. It appeared to be a lumbering gray mass. I took a second look. It was a group of first responders covered head to toe in ash.

I asked the driver to stop. I walked over, started shaking hands, and thanked the men for all they had done. They had been working nonstop. Several had tears running down their faces, cutting a path through the soot like rivulets through a desert. The emotion of the encounter was a harbinger of what was to come.

As we approached Ground Zero, I felt like I was entering a nightmare. There was little light. Smoke hung in the air and mixed with suspended particles of debris, creating an eerie gray curtain. We sloshed through puddles left behind by the morning rain and the water used to fight the fires. There was some chatter from the local officials. “Here is where the old headquarters stood. … There is where the unit regrouped.” I tried to listen, but my mind kept returning to the devastation, and to those who ordered the attacks. They had hit us even harder than I had comprehended.

We had been walking for a few minutes when George and Rudy led us down into a pit where rescue workers were digging through the rubble for survivors. If the rest of the site was a nightmare, this was pure hell. It seemed darker than the area up top. In addition to the heavy soot in the air, there were piles of shattered glass and metal.

When the workers saw me, a line formed. I shook every hand. The workers’ faces and clothes were filthy. Their eyes were bloodshot. Their voices were hoarse. Their emotions covered the full spectrum. There was sorrow and exhaustion, worry and hope, anger and pride. Several quietly said, “Thank you” or “God bless you” or “We’re proud of you.” I told them they had it backward. I was proud of them.

Читать дальше