A typical Midland day, playing baseball until sunset.

One of the proudest moments of my young life came when I was eleven years old. Dad and I were playing catch in the yard. He fired me a fastball, which I snagged with my mitt. “Son, you’ve arrived,” he said with a smile. “I can throw it to you as hard as I want.”

Those were comfortable, carefree years. The word I’d use now is idyllic. On Friday nights, we cheered on the Bulldogs of Midland High. On Sunday mornings, we went to church. Nobody locked their doors. Years later, when I would speak about the American Dream, it was Midland I had in mind.

Amid this happy life came a sharp pang of sorrow. In the spring of 1953 my three-year-old sister Robin was diagnosed with leukemia, a form of cancer that was then virtually untreatable. My parents checked her into Memorial Sloan-Kettering in New York City. They hoped for a miracle. They also knew that researchers would learn from studying her disease.

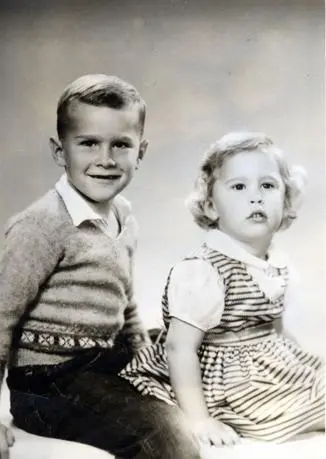

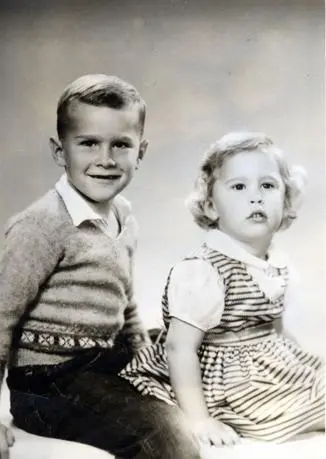

With my sister, Robin, on her last Christmas, 1952.

Mother spent months at Robin’s bedside. Dad shuttled back and forth between Texas and the East Coast. I stayed with my parents’ friends. When Dad was home, he started getting up early to go to work. I later learned he was going to church at 6:30 every morning to pray for Robin.

My parents didn’t know how to tell me my sister was dying. They just said she was sick back east. One day my teacher at Sam Houston Elementary School in Midland asked me and a classmate to carry a record player to another wing of the school. While we were hauling the bulky machine, I was shocked to see Mother and Dad pull up in our family’s pea-green Oldsmobile. I could have sworn that I saw Robin’s blond curls in the window. I charged over to the car. Mother hugged me tight. I looked in the backseat. Robin was not there. Mother whispered, “She died.” On the short ride home, I saw my parents cry for the first time in my life.

Robin’s death made me sad, too, in a seven-year-old way. I was sad to lose my sister and future playmate. I was sad because I saw my parents hurting so much. It would be many years before I could understand the difference between my sorrow and the wrenching pain my parents felt from losing their daughter.

The period after Robin’s death was the beginning of a new closeness between Mother and me. Dad was away a lot on business, and I spent almost all my time at her side, showering her with affection and trying to cheer her up with jokes. One day she heard Mike Proctor knock on the door and ask if I could come out and play. “No,” I told him. “I have to stay with Mother.”

For a while after Robin’s death I felt like an only child. Brother Jeb, seven years younger than me, was just a baby. My two youngest brothers, Neil and Marvin, and my sister Doro arrived later. As I got older, Mother continued to play a big role in my life. She was the Cub Scout den mother who drove us to Carlsbad Caverns, where we walked among the stalactites and stalagmites. As a Little League mom, she kept score at every game. She took me to the nearest orthodontist in Big Spring and tried to teach me French in the car. I can still picture us riding through the desert with me repeating, “ Ferme la bouche … ouvre la fenêtre .” If only Jacques Chirac could have seen me then.

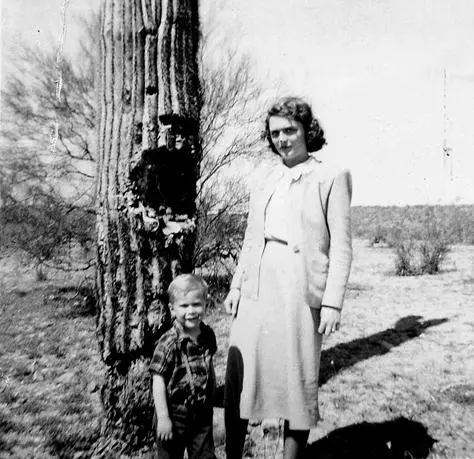

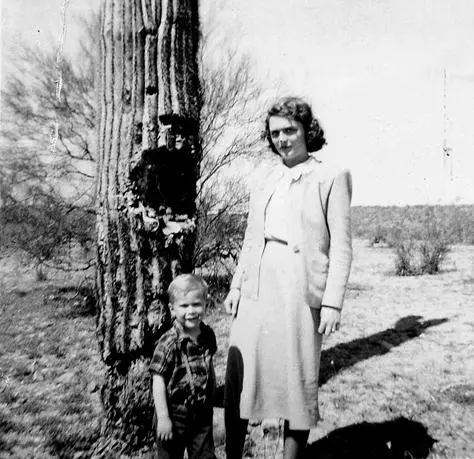

On a trip with Mother in the desert.

Along the way, I picked up a lot of Mother’s personality. We have the same sense of humor. We like to needle to show affection, and sometimes to make a point. We both have tempers that can flare rapidly. And we can be blunt, a trait that gets us in trouble from time to time. When I ran for governor of Texas, I told people that I had my daddy’s eyes and my mother’s mouth. I said it to get a laugh, but it was true.

Being the son of George and Barbara Bush came with high expectations, but not the kind many people later assumed. My parents never projected their dreams onto me. If they hoped I would be a great pitcher, or political figure, or artist (no chance), they never told me about it. Their view of parenting was to offer love and encourage me to chart my own path.

They did set boundaries for behavior, and there were times when I crossed them. Mother was the enforcer. She could get hot, and because we had such similar personalities, I knew how to light her fuse. I would smart off, and she would let me have it. If I was smutty, as she put it, I would get my mouth washed out with soap. That happened more than once. Most of the time I did not try to provoke her. I was a spirited boy finding my own way, just as she was finding hers as a parent. I’m only half joking when I say I’m responsible for her white hair.

As I got older, I came to see that my parents’ love was unconditional. I know because I tested it. I had two car wrecks when I was fourteen, the legal driving age back then. My parents still loved me. I borrowed Dad’s car, carelessly charged in reverse, and tore the door off. I poured vodka in the fishbowl and killed my little sister Doro’s goldfish. At times I was surly, demanding, and brash. Despite it all, my parents still loved me.

Eventually their patient love affected me. When you know you have unconditional love, there is no point in rebellion and no need to fear failure. I was free to follow my instincts, enjoy my life, and love my parents as much as they loved me.

One day, shortly after I learned to drive and while Dad was away on a business trip, Mother called me into her bedroom. There was urgency in her voice. She told me to drive her to the hospital immediately. I asked what was wrong. She said she would tell me in the car.

As I pulled out of the driveway, she told me to drive steadily and avoid bumps. Then she said she had just had a miscarriage. I was taken aback. This was a subject I never expected to be discussing with Mother. I also never expected to see the remains of the fetus, which she had saved in a jar to bring to the hospital. I remember thinking: There was a human life, a little brother or sister.

Mother checked herself into the hospital and was taken to an exam room. I paced up and down the hallway to steady my nerves. After I passed an older woman several times, she said, “Don’t worry, honey, your wife will be just fine.”

When I was allowed into Mother’s room, the doctor said she would be all right, but she needed to spend the night. I told Mother what the woman had said to me in the hall. She laughed one of her great, strong laughs, and I went home feeling much better.

The next day I went back to the hospital to pick her up. She thanked me for being so careful and responsible. She also asked me not to tell anyone about the miscarriage, which she felt was a private family matter. I respected her wish, until she gave me permission to tell the story in this book. What I did for Mother that day was small, but it was a big deal for me. It helped deepen the special bond between us.

While I was growing up in Texas, the rest of the Bush family was part of a very different world. When I was about six years old, we visited Dad’s parents in Greenwich, Connecticut. I was invited to eat dinner with the grown-ups. I had to wear a coat and tie, something I never did in Midland outside of Sunday school. The table was set elegantly. I had never seen so many spoons, forks, and knives, all neatly lined up. A woman dressed in black with a white apron served me a weird-looking red soup with a white blob in the middle. I took a little taste. It was terrible. Soon everyone was looking at me, waiting for me to finish this delicacy. Mother had warned me to eat everything without complaining. But she forgot to tell the chef she had raised me on peanut butter and jelly, not borscht.

Читать дальше