In the quarter-century separating the two executions, however, the boundaries of royal power would change in ways that even Dudley and his colleagues, with their relentless drive to enforce the king’s laws and their slavish ‘obedience to our sovereign lord the king’, could scarcely have imagined. Thomas More would die denying the supreme jurisdiction of the crown, not over its own laws and its subjects, but over the laws of God and the church. What Henry VII would have made of it can only be guessed at. He might have been appalled by his son’s single-minded, and ultimately cataclysmic, efforts to find himself a wife who could provide him with an heir and thereby secure another dynastic succession, and his equally destructive efforts to augment his income. He might also have seen him as a chip off the old block. 50

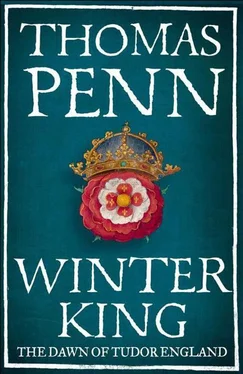

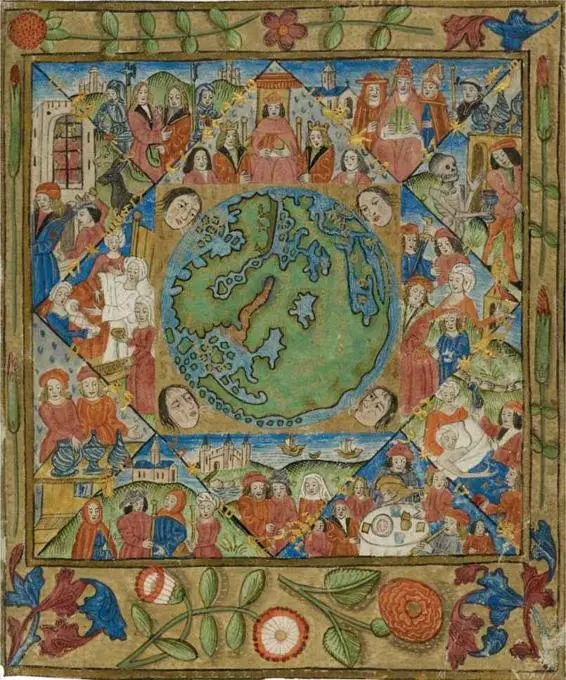

1. A miniature astrological world map, with the signs of the Zodiac and personifications of the four winds. This is the frontispiece of the ‘Liber de optimo fato’, or ‘Book of Excellent Fortunes’, by William Parron, the Italian astrologer who prophesied the deaths of Warbeck and Warwick. Given as a New Year’s gift in January 1503, the book predicts that Queen Elizabeth would live to the age of eighty.

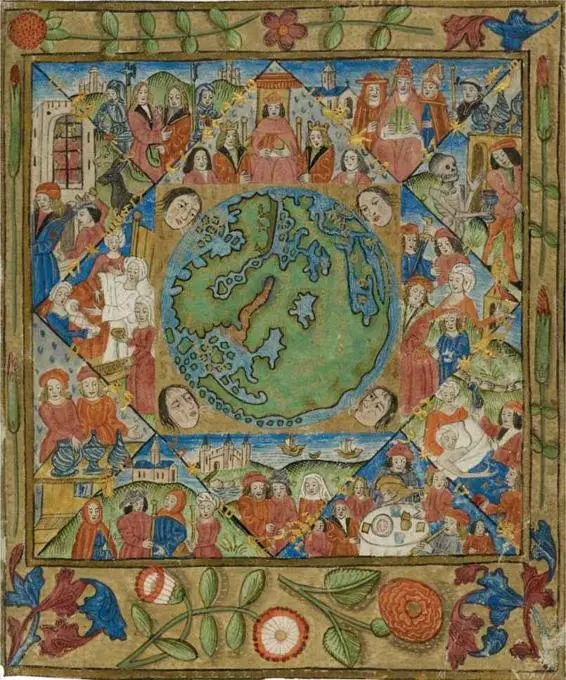

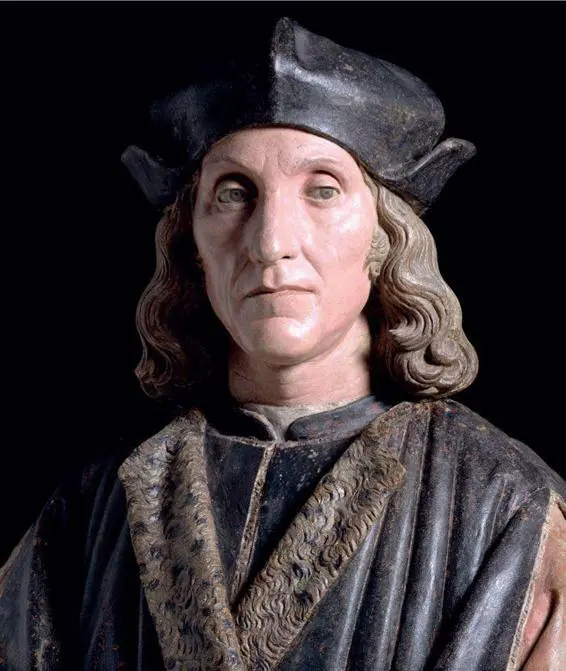

2. Terracotta portrait bust of Henry VII by Pietro Torrigiano.

3. Portrait of Elizabeth of York, Henry’s queen.

4. A laughing boy, thought to be Prince Henry aged about eight, by Guido Mazzoni, c . 1498.

5. Lady Margaret Beaufort, the pious and politicking mother of Henry VII, in characteristic dress and pose.

6. Portrait of Catherine of Aragon, aged about twenty, by Michael Sittow.

7. Richmond, ‘the beauteous exemplar of all proper lodgings’. Drawing by Antonis van Wyngaerde, c . 1562.

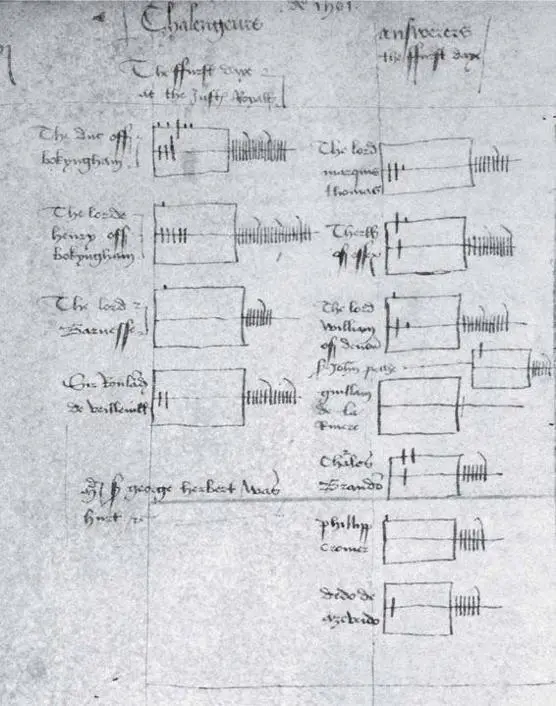

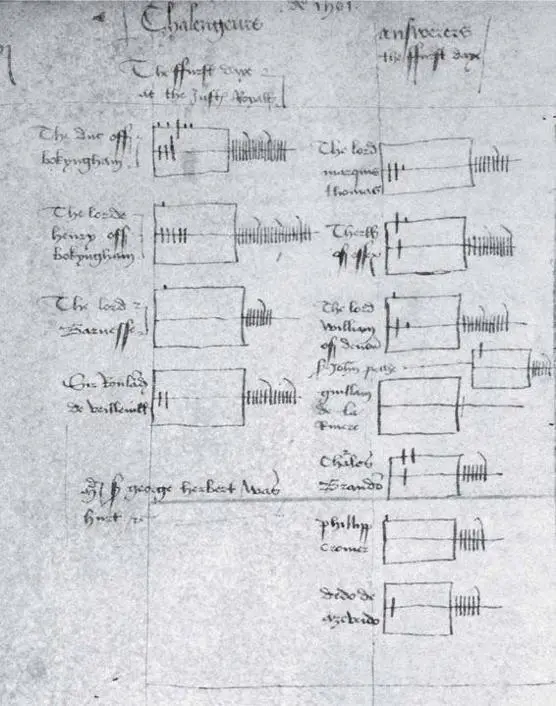

8. The ‘score cheque’ from the first day of the Westminster jousts of November 1501, celebrating the marriage of Prince Arthur to Catherine of Aragon. The columns represent the two teams. Each combatant’s score is indicated in the box next to his name: strokes indicate blows to the head or body and, bisecting the horizontal lines, lances broken. Heading the ‘challengers’ team ( left ) is the duke of Buckingham; the ‘answerers’ team ( right ) is led by ( top ) the marquis of Dorset and includes ( second ) the earl of Essex and ( third ) Lord William Courtenay, all of whom were suspected of conspiring with Suffolk. Fifth down is a youthful Charles Brandon.

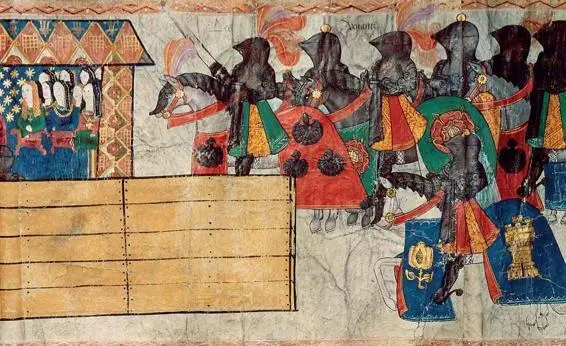

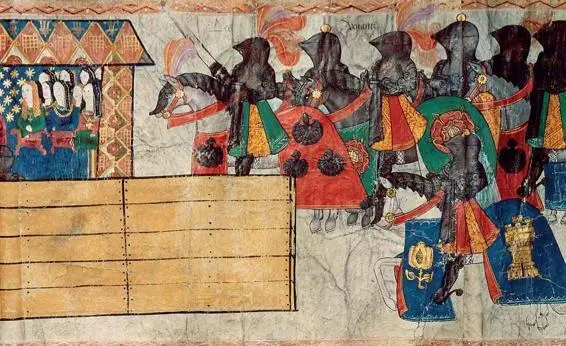

9. A group of plate-armoured jousters arrives at a tournament. These are the ‘venants’, or ‘challengers’, who take up the challenge issued on the king’s behalf. On the left, ladies of court look on from the royal pavilion.

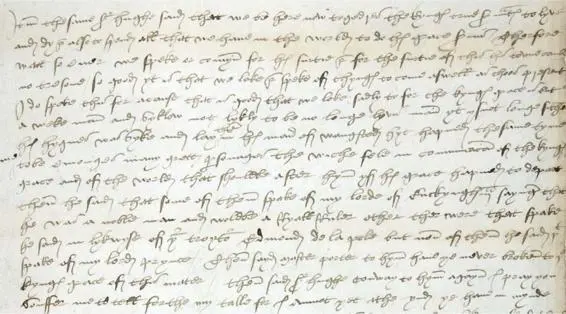

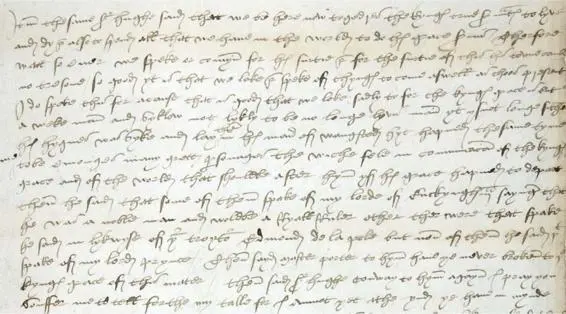

10. Informer’s report by John Flamank, detailing the secret conversation among Henry VII’s officials at Calais, September 1504. The officials describe the king as ‘a weak man and sickly, not likely to be no long-lived man’ ( line 6 ) and discuss a debate among ‘great personages’ at court over possible heirs to the throne: ‘none of them spoke of my lord prince’ ( lines 12–13 ).

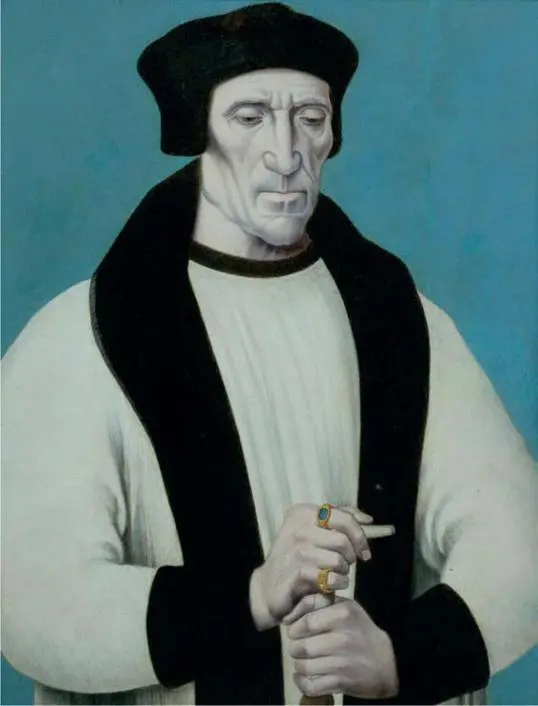

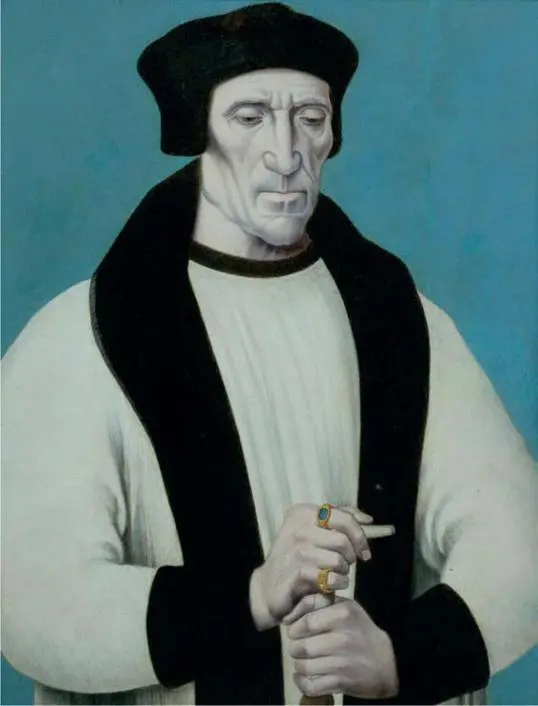

11. ‘They think he is a fox – and such is his name.’ Richard Fox, Henry VII’s lord privy seal and diplomatic mastermind. Portrait by Hans Corvus.

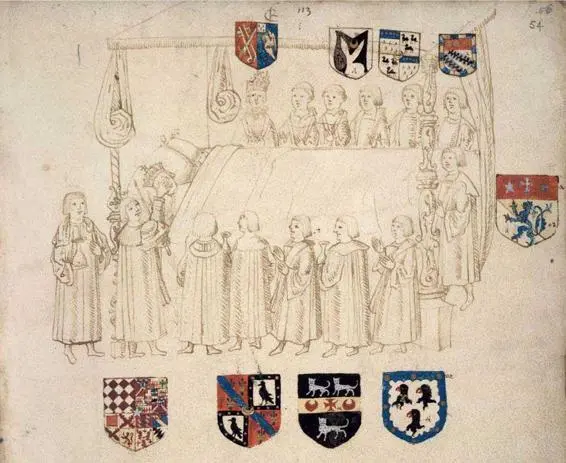

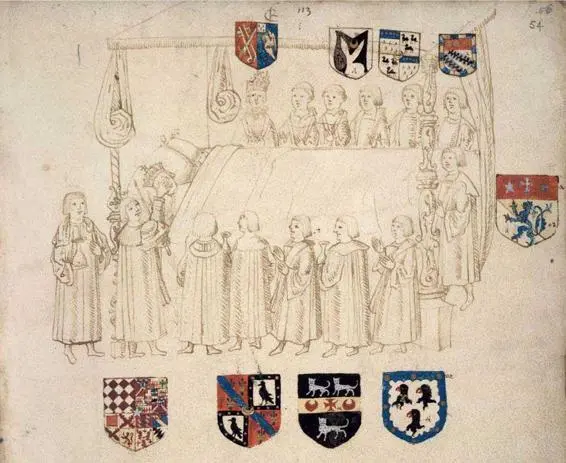

12. The death of Henry VII, ‘secretly kept by the space of two days after’. Drawing by Garter king-of-arms Thomas Wriothesley.

13. From Thomas More’s coronation verses, on the rainstorm that disrupted Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon’s procession through London, 23 June 1509: ‘if one looks at the omen, it could not have been better. To our rulers, days of abundance are promised by Phoebus with his sunshine, and by Jove’s wife with her rains.’ Below, an intertwined red-and-white rose and pomegranate of Granada, flanked by a French fleur-de-lys and Beaufort portcullis, are surmounted by a crown imperial.

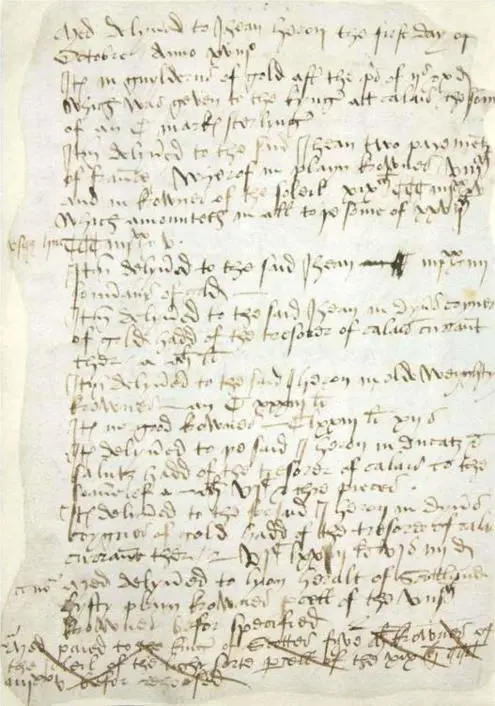

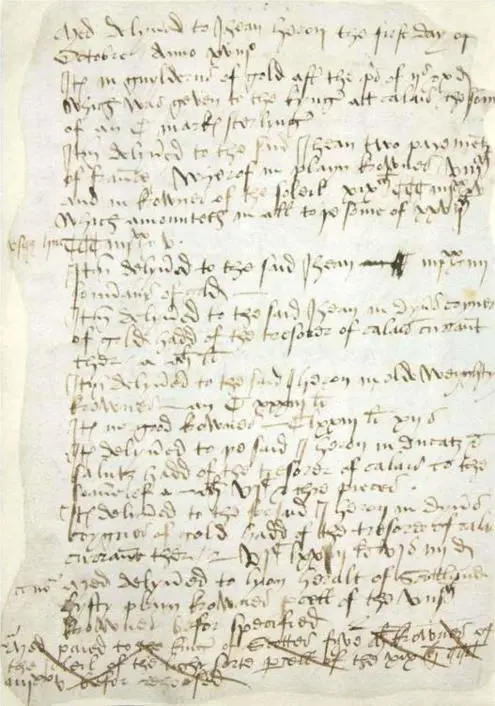

14. Henry VII’s accounts. This page, written in the king’s own hand, details monies that he himself has processed and delivered to his chamber treasurer John Heron. Items include the annual payment of Henry’s French pension in ‘plain crowns’ and ‘crowns of the soleil’ ( lines 6–8 ), ‘diverse coins of gold’ from the Calais treasurer ( lines 13–15 ) and £1,133 in ‘old weighty crowns’ ( lines 16–17 ).

Epilogue

As he sat in the Tower of London awaiting his death, Edmund Dudley set to work on a book, a treatise of advice on government, his last gesture to the young Henry VIII and his counsellors. The result, The Tree of Commonwealth , is the only full-length expression of the way one of Henry VII’s ministers thought. Using the metaphor of society as a tree, Dudley laid out a vision of an organized society divided into ranks and estates, church, nobility, commons: everything in its right place, with the king at the top, the fount of justice, order and morality. Not so subtly, Dudley repudiated the abuses of the late king’s reign, in which he had played an integral role – its unaccountability, its ‘extraordinary justice’, its ‘insatiable’ avarice. But other than that, the picture that he painted was one that had been refined and sharpened over the previous quarter-century, and one to which people had gradually become inured: that the well-being and ‘prosperous estate’ of England, and of even its most exalted subjects, depended on loyalty and service to the crown. The Tree of Commonwealth presented a vision of Tudor sovereignty, Dudley’s blueprint for the reign to come. 1

Читать дальше