THOMAS PENN

Winter King

The Dawn of Tudor England

ALLEN LANE

an imprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

For Kate

‘I love the rose both red and white.

Is that your pure, perfect appetite?’

Thomas Phelyppes,

‘I love, I love and whom love ye?’ c. 1486

‘Since men love at their own pleasure and fear at the pleasure of the prince, the wise prince should build his foundation upon that which is his own, not upon that which belongs to others: only he must seek to avoid being hated.’

Machiavelli , The Prince

List of Illustrations

1. Frontispiece of the ‘Liber de optimo fato’, or ‘Book of Excellent Fortunes’, by William Parron. (By permission of the British Library)

2. Henry VII. Terracotta portrait bust by Pietro Torrigiano. (Copyright © Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

3. Elizabeth of York, Henry’s queen. (Copyright © National Portrait Gallery, London)

4. A laughing boy, thought to be Prince Henry, by Guido Mazzoni. (The Royal Collection, copyright © 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

5. Lady Margaret Beaufort. (By permission of the Master and Fellows of St John’s College, Cambridge)

6. Catherine of Aragon, aged about twenty, by Michael Sittow. (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

7. Richmond. Drawing by Antonis van Wyngaerde, c . 1562. (Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford)

8. ‘Score cheque’ from the first day of the November 1501 jousts at Westminster, celebrating the marriage of Prince Arthur to Catherine of Aragon. (The College of Arms, London)

9. A group of plate-armoured jousters arrives at a tournament. (The College of Arms, London)

10. Informer’s report by John Flamank, detailing the secret conversation among Henry VII’s officials at Calais, September 1504. (The National Archives)

11. Richard Fox, Bishop of Winchester, lord privy seal and Henry VII’s diplomatic mastermind. Portrait by Hans Corvus. (Copyright © Corpus Christi College, Oxford, UK/The Bridgeman Art Library)

12. The death of Henry VII. Drawing by Garter king-of-arms Thomas Wriothesley. (By permission of the British Library)

13. From Thomas More’s coronation verses, on the rainstorm that disrupted Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon’s procession through London, 23 June 1509. (By permission of the British Library)

14. Henry VII’s accounts. (The National Archives)

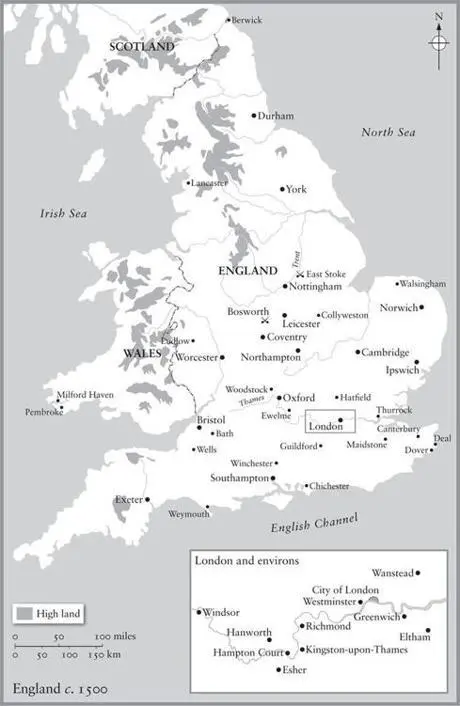

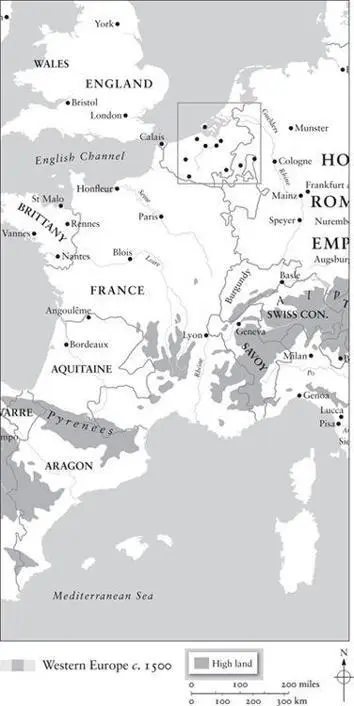

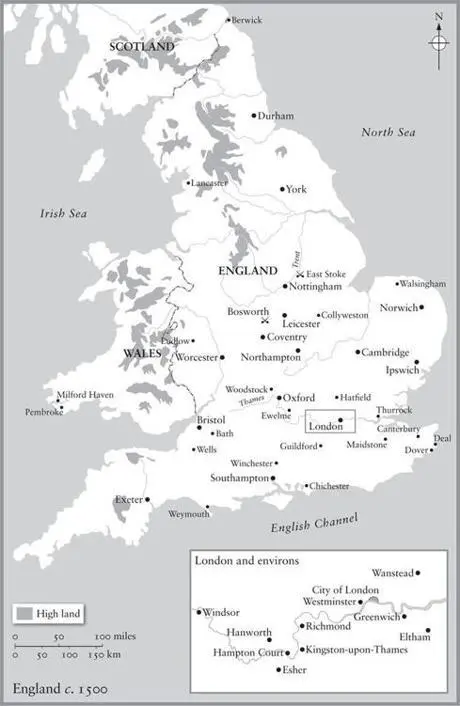

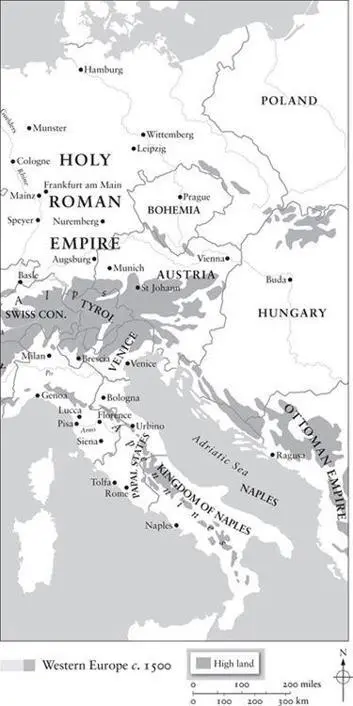

Map 1

England c . 1500

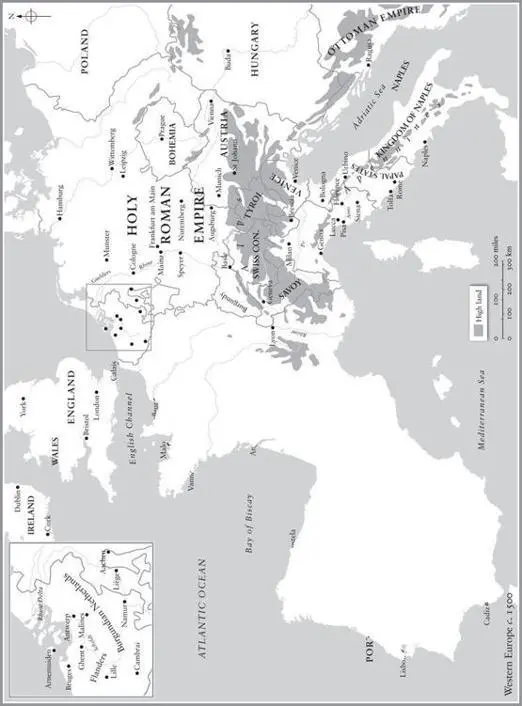

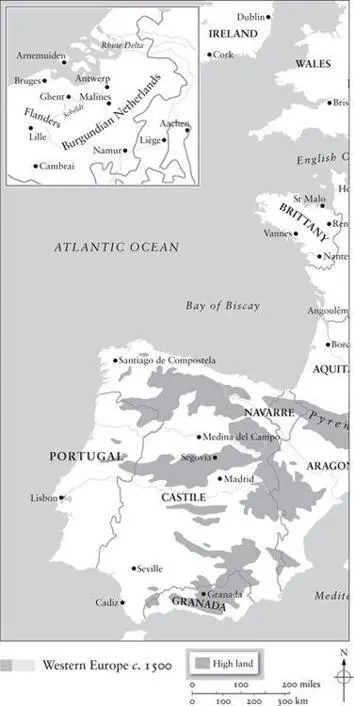

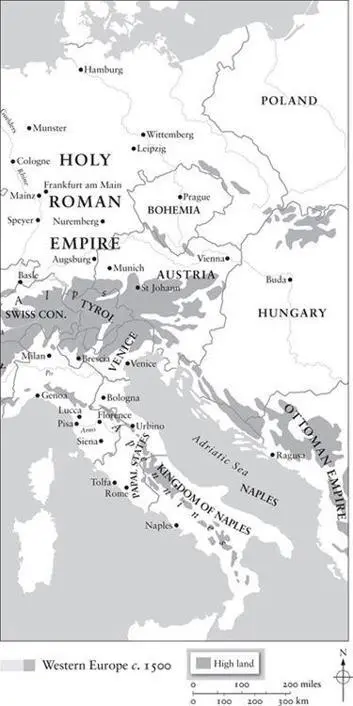

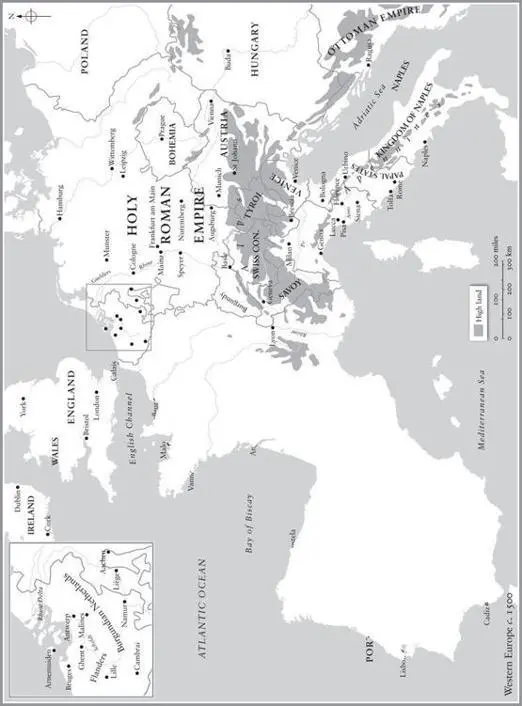

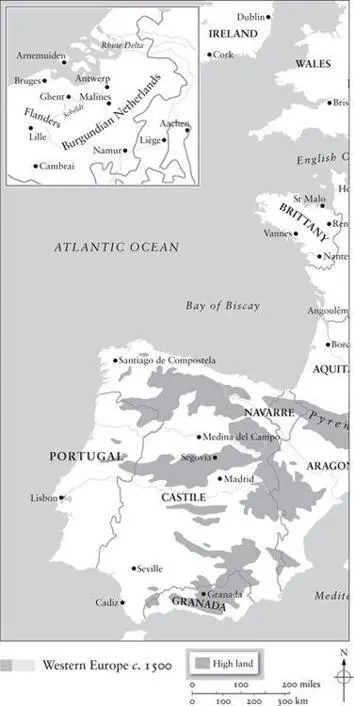

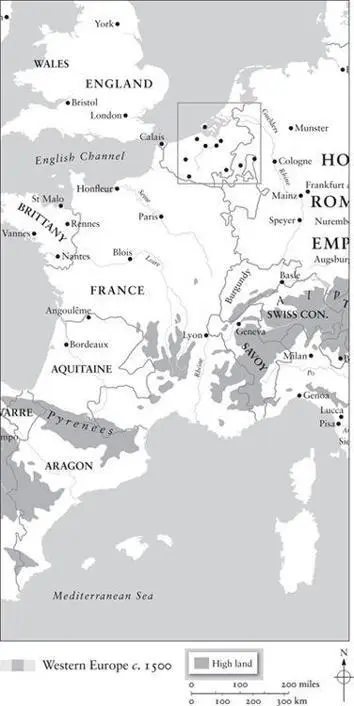

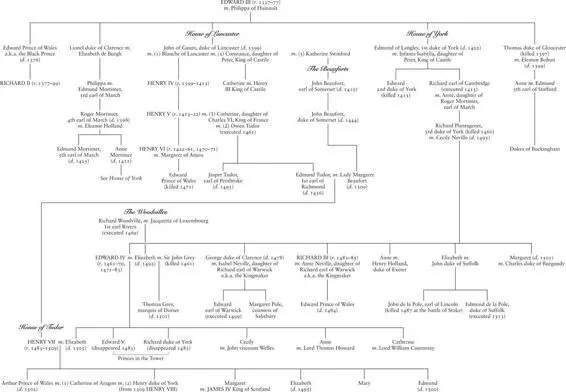

Map 2

Western Europe c . 1500

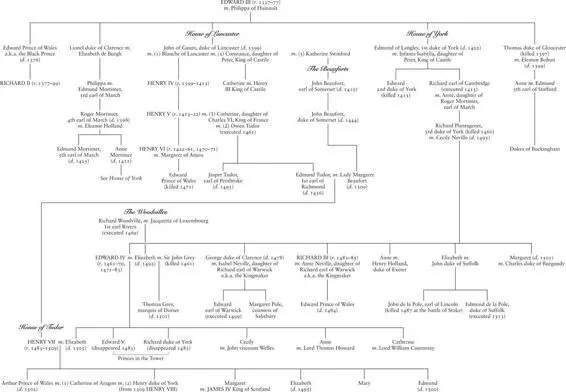

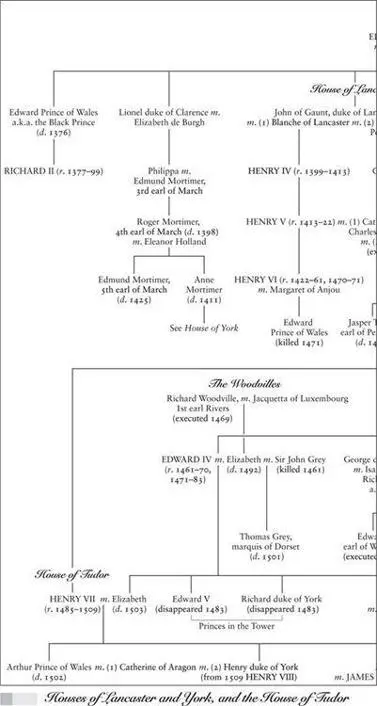

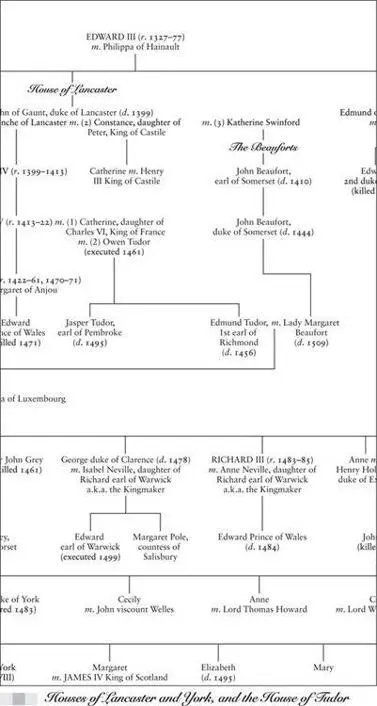

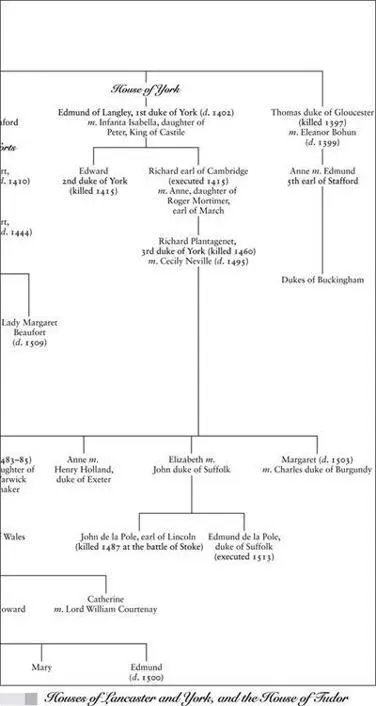

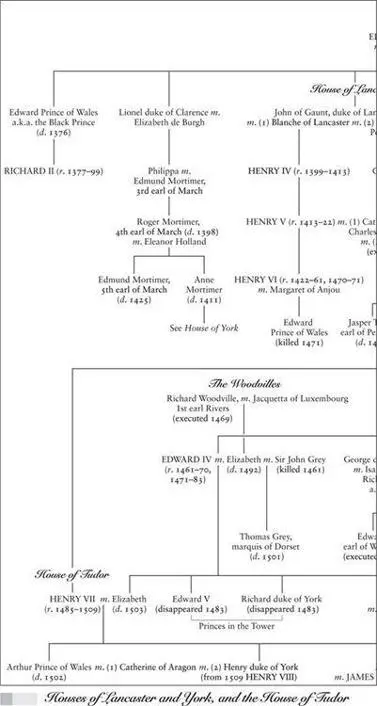

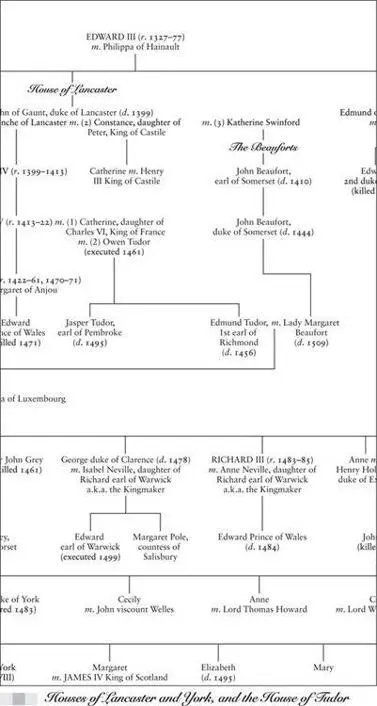

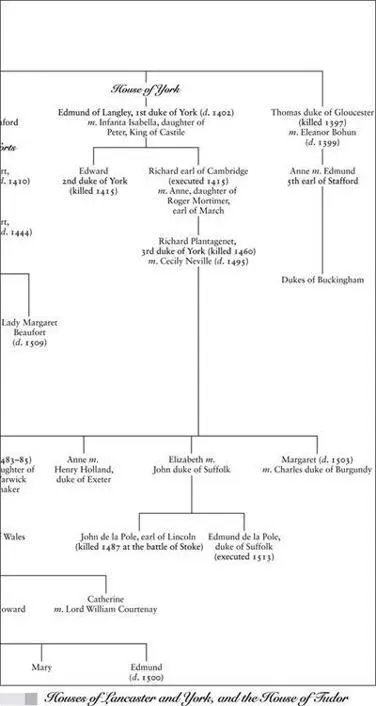

Houses of Lancaster and York, and the House of Tudor

Introduction

Henry VII ruled England for almost a quarter-century, from 1485 to 1509. During his reign, the civil wars that had convulsed the country for much of the fifteenth century burned themselves out. By its end, he had laid the foundations for the dynasty that bore his name: Tudor. He was a man with a highly dubious claim to the throne, who seized power and passed it on in the first untroubled succession in almost a century. Yet, wedged between two of the most notorious monarchs in English history – the arch-villain Richard III and the massive figure of Henry VIII – Henry VII remains mysterious, or as his first biographer, the seventeenth-century political thinker Francis Bacon put it, ‘a dark prince’.

In English history, Henry VII’s reign is still widely understood as a time of transition, one in which the violent feuds of the previous decades gave way to a glorious age of renaissance and reformation. This was the myth that the Tudors themselves built. The later Tudors referred to Henry VII as we now see him: the unifier of a war-torn land, a wise king who brought justice and stability, and who set the crown on a sound financial footing. Nonetheless they were unable to eradicate the lingering sense of a reign that degenerated into oppression, extortion and a kind of terror, at its core an avaricious Machiavellian king who inspired not love but fear. In calling him a ‘dark prince’, Bacon’s emphasis was on the sinister as well as the opaque. Henry VII, he wrote, was ‘infinitely suspicious’ and he was right to be so, for his times were ‘full of secret conspiracies and troubles’. Perhaps the most telling verdict of all is that of Shakespeare, who omits Henry VII altogether from his sequence of history plays – and not for want of material but, one suspects, because the reign was simply too uncomfortable to deal with.

Merely scratching the surface of Henry VII’s reign exposes troubling questions about his right to the crown and about the way he held on to it. From the very outset, Henry faced challenges to his rule. Unable to eradicate the taint of illegitimacy that hung around his throne, or to master a world in which the compromised loyalties and political traumas of civil war persisted, he constructed around himself a regime whose magnificence concealed the fact that it was contingent, temporary, a sustained state of emergency. And, sixteen years into his reign, just when he thought that he had laid his demons to rest, a family catastrophe left him newly vulnerable, wrenching the dynasty off the course that he had planned for it, and setting it in a new and unexpected direction, his hopes resting no longer on his first-born son but entirely on his second: the boy who would eventually succeed him as Henry VIII.

Unsurprisingly, when the seventeen-year-old Henry VIII inherited the throne in the spring of 1509, he had a difficult circle to square. His coronation was accompanied by an outpouring of praise which presented him as his father’s successor, while at the same time distancing him from the disturbing years that had just passed. Court poets reached for Plato’s tried-and-tested idea of the Golden Age: paradise, the first of epochs which, like the seasons, would return. This glorious young prince represented a metaphorical spring, a second coming, seemingly as unlike his father as could be.

It was a model that had been used before – in living memory, in fact. Back in 1485, Henry VII had evoked the Golden Age to define himself against the king he had defeated and called a usurper, Richard III. But in 1509, court poets portrayed Henry’s own reign as a sterile landscape, one in which bears roamed and wolves howled, a time in which the natural order had been subverted – but which, mercifully, was rightfully restored in the shape of his son. In other words, if Henry VIII was the spring, his father was the winter.

Читать дальше