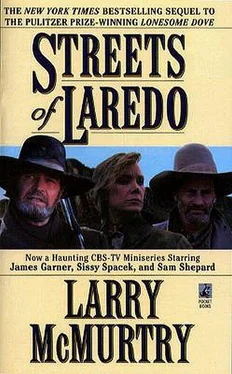

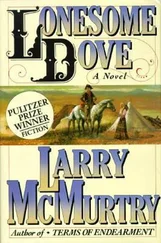

Larry McMurtry - Streets Of Laredo

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Larry McMurtry - Streets Of Laredo» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Streets Of Laredo

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Streets Of Laredo: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Streets Of Laredo»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

tetralogy is an exhilarating tale of legend and heroism. Captain Woodrow Call, August McCrae's old partner, is now a bounty hunter hired to track down a brutal young Mexican bandit. Riding with Call are an Eastern city slicker, a witless deputy, and one of the last members of the Hat Creek outfit, Pea Eye Parker, now married to Lorena -- once Gus McCrae's sweetheart. This long chase leads them across the last wild streches of the West into a hellhole known as Crow Town and, finally, into the vast, relentless plains of the Texas frontier.

Streets Of Laredo — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Streets Of Laredo», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Then, when she had made her husband as comfortable as she could make him, Lorena went back across the small room, covered Maria, and sat with her two new children, the little girl who had no sight, and the large boy with the empty mind.

In the morning, the vaqueros came back with a photographer they had found in Presidio. They wanted to have their pictures taken with the famous bandit they had killed. They had drunk tequila all night, telling stories about the great battle they'd had with the young killer. They had forgotten the butcher and the mother entirely; in their minds, there had been a great gun battle by the Rio Grande, and the famous bandit had finally fallen to their guns.

Billy Williams had obeyed Maria's last order: he drank all night, sitting outside the room where Maria lay. But the whiskey hadn't touched him, and when the vaqueros came straggling up from the river with the photographer and his heavy camera, loaded on a donkey--he planned to take many pictures and sell them to the Yankee magazines and make his fortune-- Billy Williams went into a deadly rage.

"You goddamn goat ropers had better leave!" he yelled, grabbing his rifle. The vaqueros were startled into immediate sobriety by the wild look in the old mountain man's eyes.

Billy Williams began to fire his rifle, and the vaqueros felt the bullets whiz past them like angry bees, causing them to flee. The photographer, a small man from Missouri named Mullins, fled too--but he could not persuade the donkey to flee. George Mullins stopped fifty yards away and watched Billy Williams cut the cameras off the donkey and hack them to kindling with an axe.

George Mullins had invested every cent he had in the world in those cameras. He had even borrowed money to buy the latest equipment--but in a moment, he was bankrupt. There would be no sales to Yankee magazines, and there would be no fortune.

George Mullins had ridden across the river, feeling like a coming man; he walked back to Texas owning nothing but a donkey.

All day people filed out of the countryside like ants, from Mexico and from Texas, hoping for a look at Joey Garza's body. But Billy Williams drove them all off. He fired his gun over their heads, or skipped bullets off the dust at their feet.

"Go away, you goddamn buzzards!" he growled, at the few who dared to come within hearing distance.

The people feared to challenge him, but they were frustrated. The body of the famous young killer lay almost in sight, and they wanted to see it. They wanted to tell their children that they had seen the corpse of Joey Garza. They hated the old fountain man; he was crazy. What right did he have to turn them away when they had come long distances to look at a famous corpse. He didn't own the body!

"They ought to lock up the old bastard!" one disgruntled spectator complained. He expressed the general view.

But no one came to lock up Billy. Olin Roy arrived out of deep Mexico in time to help Billy dig the two graves. Olin was silent and sad, for he, too, had loved Maria. The old sisters came and dressed Maria's body, but they would not touch Joey. Lorena finished the cleaning that Maria, in her weakness, had begun.

Pea Eye watched with Famous Shoes, who had arrived in the night while Billy Williams sat drinking. The wounds in Joey's back were terrible, and Olin and Billy both believed they would have killed Joey, in time.

"Why, he was just a young boy," Pea Eye remarked. It always surprised him how ordinary famous outlaws turned out to be, once you saw them dead. People talked about them so much that you came to expect them to be giants, but they weren't. They were just men of ordinary size, if not smaller.

"Why, Clarie's bigger than he was," Pea Eye said. All that chasing and all that pain and death, and the boy who caused it hadn't been as big as his own fifteen-year-old.

"He had pretty hands, didn't he?" Lorena said. She felt sad and low. All Billy Williams's yelling and shooting made her nervous. She could not forget Maria's anguished eyes. What a terrible grief, to have a child go bad and never be able to correct it or even know why it happened. She wondered how she would live if one of her sons came to hate her as Joey had seemed to hate Maria.

It was not a direction Lorena wanted to allow her mind to go. She didn't want such darkness in her thoughts, for she had the living to tend to. She busied herself caring for Pea Eye, Captain Call, and the two children. She thought of Maria and her bad son as little as possible. There was no knowing why such things happened. Lorena had good sons, and she knew now how very lucky she was. To have an evil child come from her own womb would be too hard to bear; Lorena didn't want to think about it.

When Pea Eye's mind cleared and he had a good look at the Captain, he was shocked.

Call was almost helpless. He let the little blind girl feed him, but otherwise, he simply lay on his pallet, barely moving. Of course, he could barely move without assistance. He only had one leg and one arm, and could not button or unbutton himself.

"You have to help him make water," Lorena told Pea Eye. "He hates for me to do it, but if somebody don't help him, he'll wet his pallet. Watch him and help him. We don't have any bedding to spare." "Why, Captain, if there was many more people as bunged up as you and me, they'd have to build a crutch factory in the Panhandle, I guess," Pea Eye said. He was trying to make conversation with the silent man. He thought of the part about the crutch factory as a little joke, but Lorena glared at him when he said it, and Captain Call did not reply. He just stared upward.

Later, Pea Eye felt bad about having made the remark. He didn't know why he had even made it, it just popped out. Though his hip pained him a good deal, Pea Eye could not help but feel good. His wife had found him, and they were together again. He wouldn't have to lose her, and he would see his children soon. Lorena was going to wire Clara to send them home when the time came for them all to go north.

The sullen doctor from Presidio had been persuaded to come and set Pea Eye's hip, but only because Lorena had gone to Presidio herself and refused to take no for an answer. She had waited sternly in the doctor's office until he saddled a horse and came back with her. He said Pea would be walking without a crutch in two months, just in time for planting. His shoulder was already almost healed, and the two toes Joey shot off he could do without. Mox Mox and Joey Garza were dead, but he himself had survived. He had also learned his lesson, and learned it well. He would never leave his family again.

"Why'd you have to say that about the crutch factory?" Lorena whispered to him that night. The remark had startled her. Pea Eye had never made a joke in his life--why that one at that time?

"He'll never forgive you for saying it, and I don't blame him," she went on. "You're just hurt, Pea. In two months you'll be as good as new. But the Captain is crippled for life.

He's crippled, for life!

"You better just shut up about crutch factories!" she whispered later, with unusual vehemence.

Pea Eye came to feel that his chance remark was the worst thing he had ever said in his life. His main hope was that the Captain would just forget it. But the Captain said so little to anyone that it was hard to know what he was remembering or forgetting. The Captain just lay there. He only fought when Pea Eye tried to help him relieve himself, struggling with his one weak hand. His struggles unnerved Pea Eye so much that he did a poor job the first time, and he made a mess. This incompetence annoyed Lorena to the point that she ignored the Captain's objections and helped him herself after that.

"You'll have to learn to do things for him, Pea," Lorena said. "He's helpless. He'll have to live with us for a while, I guess. I told Maria I'd take her children, and we've got them to think about, too. We're both going to have all we can do. You better make up your mind to start helping Captain Call. You have to help him now whether he likes it or not. You know the man. You worked for him most of your life. He don't like it when I help him. I don't know whether he just don't like me, or whether it's because I'm a woman, or because I was what I was, once ... I don't know. But we're going to have all we can do, both of us, and the Captain ought to be your responsibility." "Why, that little blind girl takes care of him pretty well herself," Pea said. Indeed, Teresa's attentiveness and the Captain's acceptance of it surprised him. He had never known the Captain to cotton to a child. He had never even come to visit their children, and he and Lorena had five.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Streets Of Laredo»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Streets Of Laredo» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Streets Of Laredo» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.