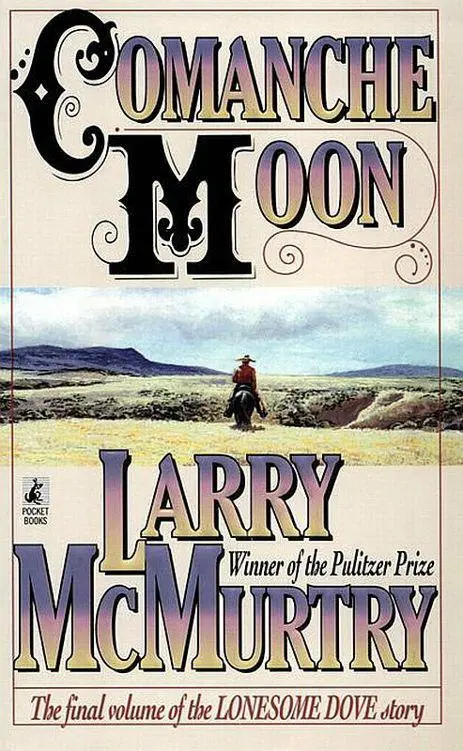

COMANCHE MOON

By Larry McMurtry

Book I

Captain Inish Scull liked to boast that he had never been thwarted in pursuit--as he liked to put it--of a felonious foe, whether Spanish, savage, or white.

"Nor do I expect to have to make an exception in the present instance," he told his twelve rangers. "If you've got any sacking with you, tie it around your horses' heads. I've known cold sleet like this to freeze a horse's eyelids, and that's not good. These horses will need smooth use of their eyelids tomorrow, when the sun comes out and we run these thieving Comanches to ground." Captain Scull was a short man, but forceful. Some of the men called him Old Nails, due to his habit of casually picking his teeth with a horseshoe nail--sometimes, if his ire rose suddenly, he would actually spit the nail at whoever he was talking to.

"This'll be good," Augustus said, to his friend Woodrow Call. The cold was intense and the sleet constant, cutting their faces as they drove on north. All the rangers' beards were iced hard; some complained that they were without sensation, either in hands or feet or both. But, on the llano, it wasn't yet full dark; in the night it would undoubtedly get colder, with what consequences for men and morale no one could say. A normal commander would have made camp and ordered up a roaring campfire, but Inish Scull was not a normal commander. "I'm a Texas Ranger and by God I range," he said often. "I despise a red thief like the devil despises virtue. If I have to range night and day to check their thieving iniquity, then I'll range night and day." "Bible and sword," he usually added. "Bible and sword." At the moment no red thieves were in sight; nothing was in sight except the sleet that sliced across the formless plain. Woodrow Call, Augustus McCrae, and the troop of cold, tired, dejected rangers were uncomfortably aware, though, that they were only a few yards from the western edge of the Palo Duro Canyon. It was Call's belief that Kicking Wolf, the Comanche horse thief they were pursuing, had most likely slipped down into the canyon on some old trail. Inish Scull might be pursuing Indians that were below and behind him, in which case the rangers might ride all night into the freezing sleet for nothing.

"What'll be good, Gus?" Woodrow Call inquired of his friend Augustus. The two rode close together as they had through their years as rangers.

Augustus McCrae didn't fear the cold night ahead, but he did dread it, as any man with a liking for normal comforts would. The cold wind had been searing their faces for two days, singing down at them from the northern prairies. Gus would have liked a little rest, but he knew Captain Scull too well to expect to get any while their felonious foe was still ahead of them.

"What'll be good?" Call asked again. Gus McCrae was always making puzzling comments and then forgetting to provide any explanation.

"Kicking Wolf's never been caught, and the Captain's never been run off from," Gus said.

"That's going to change, for one of them. Who would you bet on, Woodrow, if we were to wager--Old Nails, or Kicking Wolf?" "I wouldn't bet against the Captain, even if I thought he was wrong," Call said. "He's the Captain." "I know, but the man's got no sense about weather," Augustus remarked. "Look at him.

His damn beard's nothing but a sheet of brown ice, but the fool keeps spitting tobacco juice right into this wind." Woodrow Call made no response to the remark. Gus was over-talkative, and always had been. Unless in violent combat, he was rarely silent for more than two minutes at a stretch, besides which, he felt free to criticize everything from the Captain's way with tobacco to Call's haircuts.

It was true, though, that Captain Scull was in the habit of spitting his tobacco juice directly in front of him, regardless of wind speed or direction, the result being that his garments were often stained with tobacco juice to an extent that shocked most ladies and even offended some men. In fact, the wife of Governor e. m. Pease had recently caused something of a scandal by turning Captain Scull back at her door, just before a banquet, on account of his poor appearance.

"Inish, you'll drip on my lace tablecloth.

Go clean yourself up," Mrs. Pease told the Captain--it was considered a bold thing to say to the man who was generally regarded as the most competent Texas Ranger ever to take the field.

"Ma'am, I'm a poor ruffian, I fear I'm a stranger to lacy gear," Inish Scull had replied, an untruth certainly, for it was well known that he had left a life of wealth and ease in Boston to ranger on the Western frontier. It was even said that he was a graduate of Harvard College; Woodrow Call, for one, believed it, for the Captain was very particular in his speech and invariably read books around the campfire, on the nights when he was disposed to allow a campfire. His wife, Inez, a Birmingham belle, was so beautiful at forty that no man in the troop, or, for that matter, in Austin, could resist stealing glances at her.

It was now full dusk. Call could barely see Augustus, and Augustus was only a yard or two away. He could not see Captain Scull at all, though he had been attempting to follow directly behind him. Fortunately, though, he could hear Captain Scull's great warhorse, Hector, an animal that stood a full eighteen hands high and weighed more than any two of the other horses in the troop. Hector was just ahead, crunching steadily through the sleet. In the winter Hector's coat grew so long and shaggy that the Indians called him the Buffalo Horse, both because of his shagginess and because of his great strength.

So far as Call knew, Hector was the most powerful animal in Texas, a match in strength for bull, bear, or buffalo. Weather meant nothing to him: often on freezing mornings they would see Captain Scull rubbing his hands together in front of Hector's nose, warming them on his hot breath. Hector was slow and heavy, of course--many a horse could run off and leave him.

Even mules could outrun him--but then, sooner or later, the mule or the pony would tire and Hector would keep coming, his big feet crunching grass, or splashing through mud, or churning up clouds of snow. On some long pursuits the men would change mounts two or three times, but Hector was the Captain's only horse.

Twice he had been hit by arrows and once shot in the flank by Ahumado, a felonious foe more hated by Captain Scull than either Kicking Wolf or Buffalo Hump.

Ahumado, known as the Black Vaquero, was a master of ambush; he had shot down at the Captain from a tiny pocket of a cave, in a sheer cliff in Mexico. Though Ahumado had hit the Captain in the shoulder, causing him to bleed profusely, Captain Scull had insisted that Hector be looked at first. Once recovered, Inish Scull's ire was such that he had tried to persuade Governor Pease to redcl war on Mexico; or, failing that, to let him drag a brace of cannon over a thousand miles of desert to blast Ahumado out of his stronghold in the Yellow Cliffs.

"Cannons--y want to take cannons across half of Mexico?" the astonished governor asked. "After one bandit? Why, that would be a damnable expense. The legislature would never stand for it, sir." "Then I resign, and damn the goddamn legislature!" Inish Scull had said. "I won't be denied my vengeance on the black villain who shot my horse!" The Governor stood firm, however. After a week of heavy tippling, the Captain-- to everyone's relief--had quietly resumed his command. It was the opinion of everyone in Texas that the whole frontier would have been lost had Captain Inish Scull chosen to stay resigned.

Now Call could just see, as the sleet thinned a little, the white clouds of Hector's breath.

Читать дальше