I dismissed that as irrelevant. "So did Constantine's. What happened between Seneca and Theodosius?"

Caius shook his head. "No one really knows, it seems, but Seneca was close to Valentinian, and that would not endear him to Theodosius in any way. " He was interrupted by the clamour of a flurry of crows that came swooping down over the rooftop, haggling viciously over some morsel of carrion that one of them clutched in its beak. We watched them until they swirled away, neither of us making any effort to compete with their raucous uproar.

"In any event, " he continued eventually, "the Emperor handed down an ultimatum that I find interesting. He made it known that Seneca, and several others like him, were doing little for the common good. How did he phrase it? 'They are depriving the Empire of the benefits of their station, experience and breeding. ' That was it. The upshot of it was that Seneca should undertake a period of public service, under implicit threat of forfeiture of all his worldly goods. I thought it quite ingenious. "

"How? What do you mean, 'ingenious'?"

His eyebrow went up. "Think about it. Seneca could refuse an imperial edict only under penalty of forfeiture of all his wealth. The alternative —

acceptance — also puts his wealth at the Emperor's disposal for all intents and purposes. You may be sure Theodosius will find a post for Seneca that will make optimum use of his financial capabilities, and that Seneca will bestir himself to enlarge his wealth while in the imperial service. But no matter what Seneca does — short of absolute, treasonous theft on a vast scale — Theodosius will benefit by it and from it. Rest assured that the Empire will be keeping a very close and meticulous watch on its richest citizen and servant. "

"And Seneca accepted that?"

"How could he do otherwise? He has not the heart to live as a pauper, and were he to attempt it, my friend in Rome swears he would not survive the first day. "

I whistled in wonder as the implications of what I had been told began to hit home to me. "Then he will be at the Emperor's bidding for a while. I wonder how he will come out of it?"

Caius cleared his throat in disgust. "Probably very well. He is still a Seneca. But he will be under some restraint. Theodosius will watch him closely, as I said, but I have no doubt that Caesarius Claudius Seneca will contrive somehow to continue to enlarge his fortune. " He was to be proven prophetic within the month.

Shortly after our conversation, Caius invited Andros's two brothers to come live at the villa in return for their parchment-making services. They accepted his invitation and began making parchment specially for us, and Caius began to write. He did not find it easy at first. He had the discipline to marshal his time but not, as he soon discovered, his thoughts. There were too many things that he wanted to write about, and he quickly found that the greatest danger lay in writing too much about too little. Eventually, however, he fell into a way of writing about whatever caught his interest at that particular time. And eventually, too, it became a habit to discuss his ideas with me.

He wrote down his thoughts and theories on life in general, and on the life and past times of Britain. We talked of the kings of Rome, and of how Rome had foresworn such men. We talked of the Republic that was born, and had lived in glory until the advent of the Caesars — Julius and his cousin Octavius, who became Caesar Augustus.

From that moment on, for all intents and purposes, the kings had returned. They called themselves emperors, but they were kings, with all the powers of despots. And they had killed Rome.

We talked also, at great length, of Britain and her future, for Caius honestly believed in God's great plans for this green land. On most of these occasions, Luceiia was with us, and her contributions to our discussions were insightful and refreshing. During those long winter nights I learned fully to appreciate the keen intellect that underlay her beauty. She astonished me most particularly one night by proposing the thought that Rome had starved to death, and she went on to support her thesis. The mother country, she pointed out, is largely infertile. It could never produce enough food for its citizens, so they turned to conquer fertile lands. And, of course, the fertile lands they conquered were never rich enough to feed their own people and Rome, too, and so it went on, to embrace the whole world.

Britain, my love believes, will never starve. The soil is rich and fruitful. As the people grow, she says, they will clear the forests and till the soil. I believe she is correct in this, for the people here are strong. The local Celts are a noble people — industrious for the most part, proud, certainly quick to anger but equally quick to forgive — and great lovers of music and the arts. The quality she finds most admirable among them, however, and I agree with her in this, is their mutual respect. The Celtic wife and mother is no chattel. She fights as well as her man, making the Celtic family a unit to be dealt with respectfully. No domestic decisions are made without her advice and concurrence. She has dignity and pride of place, as did the Republican women of Rome, and she is skilled, like the Roman matrons of old, in the arts of weaving, pottery and the rearing of children to respect all that a child should respect. When Luceiia talked of all of this the first time, I earned myself a savage clout on the head by remarking with a smile that four hundred years of Roman occupation had bred much Romanism into these Celts.

Those were idyllic days, but they were soon to be marred by a development that seemed at first to contain no hint or threat of disruption.

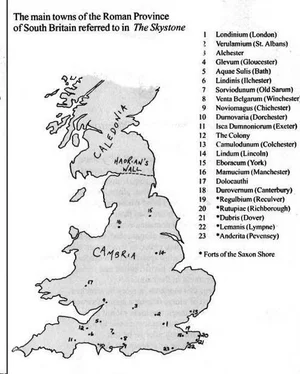

Caius received a missive from Antonius Cicero, welcoming him back to Britain and advising him of three things, the first of which was my own official death. I had been found in a ditch far to the south of Verulamium, my identity established only by a lozenge of silver with my name on it that was found in my scrip. The second piece of news was that my house had reverted to the State and would be occupied by the new Procurator, Claudius Seneca, who had been appointed to fill the post left vacant by the retirement of the incumbent. He was expected to arrive in Colchester at any time, contingent upon weather conditions in the seas between Britain and Gaul!

That was an ironic twist that had its effect on all of us! But it was followed by another even stranger, at least to me. Equus, as my beneficiary, had taken all of my belongings into his own possession, and, apparently disheartened by my disappearance and death, he had closed down the smithy, loaded everything onto a couple of wagons and left Colchester to establish himself in some other town. I was mystified by this. Where would he have gone? He knew I was not dead. Could he be coming here? To return my belongings? If so, why wouldn't Tonius have said so?

Caius put my mind at rest on that one, chiding me for being too literal in my interpretations. Of course, he said, Equus would be headed this way. But the letter from Tonius was quasi-official, carried by a military courier and therefore subject to censorship. How could Tonius make any reference, no matter how oblique, to my continued survival if there was the slightest consideration of the letter being exposed to scrutiny? Tonius, he insisted, was intelligent enough and experienced enough to know that Caius would put his own interpretation on the letter and draw his own conclusions. In the meantime, he had apprised us that I was now considered dead and therefore no longer pursuable. Furthermore, he had informed us, in plainest and yet unimpeachable terms, that my enemy was back in Britain in a position of power, and my friend was on his way to join us with my worldly goods.

Читать дальше