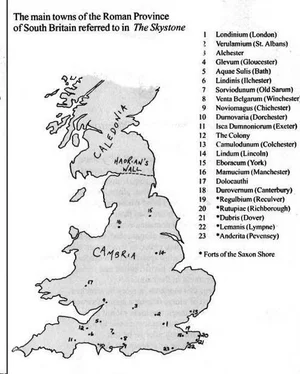

What to do? This was a dilemma I had faced before. The enemy was vanquished, but justice had not been done. We should have had prisoners — wounded, at least. Some should have survived. I found myself looking at the heaped dead and recalling the words of condemnation uttered centuries earlier by a chieftain of the Picts: "They make a desert and they call it peace. " He had been describing the atrocities of Julius Agricola's army when it attempted to conquer the highlands of Caledonia, and my grandmother had adopted his words as her favourite expression for the inhumanity of the military mind.

I sighed to myself and sent for the centurion who had commanded the rear guard, only to find that he was dead. So were his two decurions, which left no one in authority over the surviving soldiers of the squadron. Then I knew what had happened: fear, excitement, blood-lust and the need for vengeance had run rampant here among these young, untested soldiers.

Feeling like a hypocrite, I assembled them and excoriated them, telling them all a few blistering truths about responsibility and about murder. Certainly, they were soldiers, but they were also Christians, each of them having sworn his oath of loyalty upon the cross, and the Christian Commandment was specific: Thou shalt not kill. In the heat of battle, I told them, there was remission; then, kill or be killed took precedence over the Commandment. Afterwards, however, when the danger passed, the rule resumed its dominance. The killing of any man who was no longer fighting was murderous.

I was careful to look at no single man too closely during this harangue, and to make no specific accusations, for this particular task struck home to my own innermost problems, and I knew too well the despair I felt from time to time to want to foist anything like it onto these young men. They had done well, after all, in their first engagement. I excused them on the grounds of their lack of experience and let them off the hook with a stern warning that, in future, they would be held responsible for such atrocious slaughter. When I had finished, I assigned one of my own men to them as acting centurion and sent them back to the Colony with the news of the raid, while I continued with the remainder of my men towards Aquae Sulis.

BOOK FIVE - The Dragon's Breath

XXX

Two days later, on a dull, overcast afternoon in Aquae Sulis, I was still pondering "the soldier's dilemma, " as I thought of it. When is it permissible to kill and when is it not? I had discussed the matter in the past with Caius and with Bishop Alaric, and at no time had we reached a satisfactory conclusion either way. The existence of the soldier is predicated upon a perceived need to kill, for any of a dozen reasons, and yet the Christian law is categorical and absolute: Thou shall not kill. I had just purchased a wagonload of hemp for rope-making and had left my retainers to load it while I made my way to the public mansio to eat. I was deep in thought and more or less unconscious of my surroundings when I gradually became aware of a commotion ahead of me in the crowded street. Had I been less preoccupied, I might have noticed it sooner and gone around another way, but by the time I became aware of it, I was in the marketplace and surrounded by a densely packed crowd. I made my way with some difficulty to the edge of the roadway and hoisted myself precariously on a raised gutter-stone, bracing myself with my hands on the shoulders of the man in front of me and lifting my head above the crowd to see what was going on.

A horse-drawn coach, a wealthy man's conveyance, took up almost the whole of the thoroughfare just ahead of where I stood, and as I looked, its grossly fat occupant was hauling himself up from the cushioned seat, preparing to climb down. An expression of distaste was stamped on his face as he scanned the crowd that thronged around him. gawking at his wealth. His retainers bustled about, forming a wedge and clearing a pathway through the crowd to the entrance of the building he was obviously headed for. less than four good paces from where I stood, perched on my small eminence. One of these retainers, a mindless-looking hulk with the face of an ape, pushed an old woman roughly from his path with a shout.

"Way! Make way for Quinctilius Nesca!" So unexpected was the name, here in this place, that my head flew up in shock and I jerked my eyes back to the occupant of the coach. He was just on the point of stepping down into the street, and willing hands were supporting his huge arms to ease his grotesque weight. As I turned my face towards him, our eyes met. It must have been my expression of surprise and shock that alerted him, for there was nothing else to distinguish my face among the multitude. His eyes narrowing, he reached his right hand back to the framework of the open coach, holding himself there, half in and half out of the conveyance as he stared at me, and I saw suspicion dawning in his eyes. Too late, I cursed the vanity that had made me keep my grizzled beard, for in a Roman town a well-trimmed beard stands out among clean-shaven faces and wild, unkempt bushes. I hung there frozen, my eyes locked on his, incapable even of looking away from him as I saw his hand come up and point at me and his mouth frame the unheard words, "You there! Come here!"

My skin crawled with panic, for I knew I was staring death in the face and I could not move. I thought of brazening the confrontation out, but I knew that my first limping step would betray me. All he had seen until now was my grey beard, but something in the look of me had alerted him; let him once see my crippled gait and I would be dead meat. Now he was shouting, drawing the attention of his men to where I was perched, looking down on them.

"Bring that man to me!" He was yelling, pointing at me. "That one! The grey-beard there!" The simian-faced brute closest to me had turned and seen me, and now he started to move towards me through the densely packed bodies separating us, his clawed fingers stretching to take hold of me. The sight of his blackened, snarling teeth brought me to my senses. I shoved the man whose shoulders I had been leaning on right into his grasp, sending both of them reeling as I threw myself backwards into the crowd. As I disappeared from view I heard a howl go up, and I knew that I was running for my life. I used my shoulders like battering rams, ploughing through the crowd, aware of the fright and incomprehension on the faces of the people I was jostling. Then suddenly I was free of the press and diving into a narrow passageway between two buildings. It was a short alleyway leading to a common midden behind the tenements that fronted the street, I came out into this and dodged to my right, along the wall, hearing as I did so the clatter of running feet in the alley behind me. I was running hard in the style I had developed, a series of limping leaps, using my bad leg only to balance me for the next leap with my good one. It was awkward and not at all aesthetic, but it covered ground at a good rate over short distances.

An open door appeared on my right almost immediately and I swung myself inside, into near-total darkness. It was a stable of some kind, full of straw and animal smells. I saw the dim outline of a ladder ahead of me, stretching up in darkness to a second level, but it did not attract me. I had not run far enough yet to hide, and the chase was too hot behind me. I flung myself into a dark corner by the door, pressing myself back into the wall behind an untidy sprawl of forks and shovels, and drew my sword. I listened to the running feet approach and come to a stop outside the open door, less than a step from me had the wall not been between us. There were two men, both of them breathing heavily. I held my own breath, feeling the pulse hammering in my throat, hearing the silence of their motionless pause grow and extend for an impossible length of time. As clearly as if I could see them, I knew they were standing side by side, peering into the blackness beyond the doorway where I stood. Gradually their breathing steadied and then one of them spoke.

Читать дальше