We dug embrasures and soon began to erect strong wooden fortifications in strategic places. And eventually, as the work progressed, we began to build a stone-walled citadel. It became the norm that, in addition to his standard duties and to the normal stone-gathering activities of the work crews, each man was required to find one stone each day and take it to the hill, and our stonemasons were set to work to build a mighty wall.

It was slow, tedious work in the first two years, and Caius worked hard to keep people's enthusiasm for the project high. He reminded them constantly of the legend of Rome's walls, finding a thousand different ways to remind them how strong those walls had been, down through the centuries, and pointing out frequently how easy it was to see how Remus had angered Romulus by jumping across the "walls" of Rome. He urged them, all the time, every day of every week of every month, to watch the progress of their own work and to watch the progress of the work as a whole. And sure enough, as day followed day and stone was laid on stone, year in, year out, the shape of our walls became more pronounced, more evident, so that now a man could see what would be there, in time. Apart from my struggles to smelt the skystone, and to drill new soldiers, my days were filled with ironwork. I had apprentices in plenty now, and I taught them how to smelt, and how to forge new tools and weapons. I had organized some of the local Celts to find the scarce iron ore of the local hills and bring it to our smelters. In return, I made them goods and taught them Roman skills in ironwork. Some of their ironsmiths became friends, attracted, I suppose, by that mutual respect that exists among professionals of any kind, and Caius remarked with a smile one evening that my smithy had become the liveliest place in the Colony. Cymric, the Celtic bowman whom I had met on my arrival here in the west, became a regular visitor, and because of that I still practised regularly with my great African bow of horn and sinew. The fame of that bow soon spread, for the hill people were avid archers, and the Pendragon men in particular were awed by it. One day, one of them made me a gift of several dozen arrows, beautifully made, flighted with coloured feathers and tipped with iron barbs. They had been made especially for my bow, I knew, for those the Pendragon used were half the length. I was delighted with them and reciprocated with an axe of solid bronze, after which I became friends with the fletcher, who was Cymric's brother, and allowed both of them the use of the bow. Cymric used to spend hours with the great bow on his knees, studying its design.

By the end of the third year, 386, we were strongly established. We had a private army of six hundred well-trained soldiers" who could march all day and dig a fortified camp at the end of it, break it down next morning and fill the ditch before marching all day again.

And as the time went past, our numbers grew. Not a month passed without some new arrival landing in our midst: carpenters and cobblers; coopers and coppersmiths. All were made welcome and put to work at once. We soon had six shoemakers among us who spent all their time in making heavy sandals, which were shod with iron nails made in a smaller forge built beside the first one.

A silversmith from Glevum joined us with three strong, young sons in their mid teens, one of whom was an artist like his father. The other two wanted nothing more in life than to be soldiers. They were our youngest recruits. Two more stonemasons came to us from the east and were quickly put to work on our fortifications.

An armourer, who had worked in the south, was sent to us by Plautus and told us that Plautus himself was still with the holding garrison in Britain, apparently having switched allegiance to Magnus. I found that hard to believe, but I was able to come up with no other explanation for either Plautus's continued existence, or for his ongoing presence in Britain. Had he spoken up at the time of Magnus's rising, he would no doubt have shared the fate of Tonius Cicero. I was grateful that he had done neither. But I wondered how he had managed to avoid having to cross to Gaul with Magnus. By rights, a soldier of his experience should never have been allowed to remain at home in a safe billet while there was fighting to be done, but Plautus, old soldier that he was, had found a way. In the meantime, having worked his ruse, whatever it was, Plautus had found the new armourer on one of his patrols and had dispatched him to find us. I had work for him before the poor fellow had had time to eat. In a short space of time we had to start building new homes to lodge all the newcomers, and a small town grew up outside the main gates of the villa. The houses were of stone, quarried in the hills and brought in by wagon. A family of thatchers had been early arrivals, so all of the new houses were strongly roofed with woven reeds, straw or grasses, depending on the season of the year when they were finished.

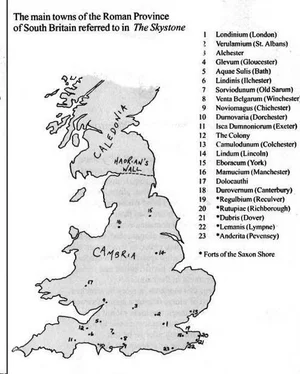

From time to time we heard rumours of increasing raids along the Saxon Shore. Magnus's departure with so many troops had not gone unnoticed, it appeared. The forces left to garrison the island were spread too thin to do a proper job, and on one of his visits, Alaric told us their morale was very low, since they were constantly faced with the problem of doing too little too late.

Like the Franks with their horses, these Saxon raiders were a new form of warrior. They came by night, landed in darkness and attacked at daybreak. They operated most of the time in single boatloads of thirty to fifty men. They could attack a hamlet, burn it, steal all that they could carry, sate their lusts for flesh and blood and be back at sea again before the word of their attack had reached the garrison troops who were supposed to stop them. The only danger they faced was the prospect of meeting a naval patrol, but the seas were big, and the patrols were few. In the autumn of 387, a boatload of Saxons infiltrated the river estuary to the north-west of us. There they left their ship and struck far inland, being careful to avoid the towns in the area and somehow managing to escape discovery.

They struck the most northerly of our villas. Fortunately, most of our people were out in the fields at the time. A squadron of our soldiers was in the area and smelled the smoke of burning thatch carried on the wind. I was in the area myself, passing by with a small escort of men and wagons on my way to Aquae Sulis for supplies. It was Lorca, one of my wagon-drivers, who made me aware that something was wrong. His nostrils were sharp, and had he not been with us we might have ridden by without noticing anything amiss. He smelled the familiar stink of burning thatch and told me what it was. Although I doubted him at first, I sent two of our strongest runners to check on it and find out where the faint smell was coming from.

Less than two hours later, I was in hiding on a shrub-covered knoll overlooking a narrow pathway that was ditched on both sides, and hoping that my cursory reading of the land and routes available had been accurate. They had, and the enemy played right into our hands. We had surprise on our side, and the fight was brief and bitter. I had split my force and found myself fighting with the larger of my groups against the enemy's vanguard, a fearsome band of brutal fighters. The majority of the raiders fell back from our first attack and found themselves cut off by our second party. I was dismounted, fighting on foot, and one of the fleeing raiders found my horse and took it. He was the sole survivor of his party, and I hope he had arms of iron for he must have had to row their long boat homeward alone.

Murder was done much further back from where I fought, where the fleeing enemy met our second fighting force. Although the men of their vanguard fought to the death and went down fighting, each and every man, the ones who fled our first attack were made of softer stuff. When I went back to check my own rear guard; I found the path littered with enemy corpses piled one on the other like firewood. Along the path of flight, all of the enemy were very soundly dead.

Читать дальше