He opened it and I saw the tears come to his eyes. He was holding my medal. He smoothed the claret ribbon on his palm. “Are you sure?”

“I’ll probably lose it.” I tried to avert any expressions of emotion.

“Things get lost on small boats.”

“They do, yes.”

“Look after it for me, will you?” I asked, trying to make it a casual request.

“I will.” He turned it over and saw my name engraved in the dull bronze. “I’ll have it put in the governor’s safe.”

“The bronze is supposed to come from Russian cannons we cap-tured at Sevastopol,” I said.

“I think I read that somewhere.” He blinked the tears away and put the medal into his pocket. The bus turned in the wide circle in front of the gate, then stopped in a shuddering haze of diesel fumes.

“I’ll see you, Dad,” I said.

“Sure, Nick.”

There was a hesitation, then we embraced. It felt awkward and lumpy. I walked to the bus, paid my fare, and sat at the back. My father stood beneath the window. A few more returning visitors climbed in, then the door hissed shut and the bus lurched forward. My father walked alongside for a few paces.

“Nick!” I could just hear him over the engine’s noise. “Nick! Paris!

Orchids! Scent! Seduction! Who dares wins!” The bus pulled away. He waved. The gears clashed as we accelerated, and then I lost him in the cloud of dust.

Duty was done.

I insisted on two bilge pumps, both manual. One was worked from the cockpit, the other from inside the cabin. George grumbled, but provided them. “Tommy shouldn’t have told you about the Dawsons,” he said.

I wondered why such a small crime worried him, but later realized it was because the London police were still searching for the forger.

George would not have cared about the local force, for he had his understanding with them, but he was leery of London.

There was a letter from London waiting for me on Rita’s desk. I eagerly tore it open, half expecting it to be from Angela, but of course she was in Paris. The letter was from Micky Harding. He was recovering. He apologized for messing up. He was sorry that the story had died. There was no evidence to support it, and such a story couldn’t run without proof. He’d floated the Kassouli withdrawal rumour to a city editor of another paper, but I’d probably seen how that story had rolled over and died. If I was ever in London, he said, I should call on him. I owed him a pint or two.

On Tuesday The Times had a photograph of Bannister’s Paris wedding. The bride wore oyster-coloured silk and had flowers in her hair. Her Baptist minister father had pronounced a blessing over the happy couple. Angela was smiling. I cut the photograph out, kept it for an hour, then screwed it up and tossed it into the dock.

I spent the next few days finishing Sycorax . I installed extra water tanks, two bunk mattresses and electric cabin lights. I also had oil-lamps, which I preferred using, just as I had oil navigation lights as well as electric ones. George found me a short-wave radio which I installed on the shelves above the starboard bunk. I screwed a barometer to the bulkhead over the chart table and bought a second-hand clockwork chronometer that went alongside it. I began stowing spare gear and equipment in the lockers, and took pride in buying a brand new Red Ensign that would fray on my jackstaff in faraway oceans. I found an old solid-fuel stove to heat the cabin. There had been a time when every cruising yacht carried such a stove, and Sycorax had always been so equipped, and I took a peculiar delight in installing the cast-iron monster. I caulked and capped the chimney in seething rain. The hot weather had gone. Cyclones were bringing squalls and cold air that made the channel choppy and promised a tumultuous wind in the far north Atlantic.

The first hopefuls set off from Cherbourg to take advantage of the Atlantic gales. An Italian crew went first and made an astonishing time to the Grand Banks, but their boat was rolled over somewhere east of Cape Race and lost its mast. Two French boats followed. I read that Bannister was honeymooning in Cherbourg while he waited for even stronger winds.

It was the wrong weather for compass-swinging, which demanded smooth water so that the delicate measurements were not joggled, but I took advantage of one sullen, drizzly day to sail between carefully plotted buoys and landmarks in Plymouth Sound. I had roughly compensated the compasses with tiny magnets that corrected the attraction of the metal in the engine and stove, but I still needed to know what other errors the needles contained, so I sailed Sycorax north and south, east and west, and courses in between, noting the compass variations on each heading. Some were big enough to demand more fiddly work with the tiny magnetic shims, which then meant that every course had to be sailed again, but I finished the job by sundown and pinned a clingfilm-wrapped correction card over my navigation table. That night I took my dirty washing to a launderette and reflected that, with a little luck, my next wash would be on shipboard where I’d use a garbage bag filled with two quarts of water and washing powder. It works as well as any electric machine.

I went to London the next day and took the children to Holland Park where we played hide and seek among the wet bushes.

Afterwards I insisted on seeing Melissa. “They’re going to kill Bannister,” I told her.

“I’m sure that’s not true, Nick.”

“He won’t listen to me,” I said.

“It’s hardly surprising, is it? I gather you declared war on him!

Are you sure you’re recovered from the Falklands? One keeps reading these tedious stories about Vietnam veterans who seem to be perfectly normal until they open fire in a crowded supermarket.

I do hope you won’t go berserk in the frozen-food section, Nick. It would be jolly hard for Mands and Pip to have a mass-murderer for a father.”

“Wouldn’t it,” I agreed. “But would you phone Bannister? He’ll listen to you. Tell him he mustn’t trust Mulder. Just convince him of that. I’ve written to him, but…” I shrugged. I’d broken my promise to Abbott by writing to Bannister. I’d written to his Richmond house, the television studios, and to the offices of his production company. I’d written because there was no proof that he was guilty of the crime for which, I was certain, he was about to be punished. Doubtless my letters had been categorized with all the other nutcase letters that a man like Bannister attracted.

Melissa ran a finger round the rim of her wine glass. “Tony won’t listen to me now, Nick. He’s married that ghastly television creature.

She’s certainly done well for herself, hasn’t she? And I’m quite sure Tony’s in that post-marital bliss thing. You know, when you swear you’ll never be unfaithful?” She laughed.

“I’m serious, Melissa.”

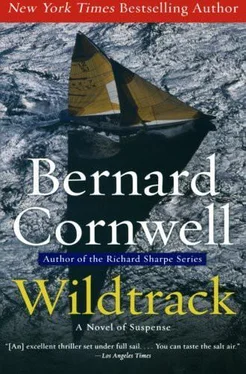

“I’m sure you are, Nicholas, but if you think I’m going to make a fool of myself by telling Tony to give up his little boat race, you’re wrong. Anyway, he wouldn’t believe me! Fanny Mulder may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but he’s completely loyal to Tony.” I’d told Melissa everything, including my new certainty that Mulder was Kassouli’s man and would navigate Wildtrack to a death.

“Phone him!” I said.

“Don’t be nasty, Nick.”

“For God’s sake, Melissa!” I closed my eyes for a second. “I’m not mad, Melissa, I’m not shell-shocked and I’m not having bad dreams.

I don’t even like Bannister. Would you believe it, my love, if I was to tell you that it could suit me hideously well if he were to die? But I just cannot stomach the thought of murder! Especially when it’s in my power to prevent it.” I shook my head. “I’m not being noble, I’m not being honourable, I just want to be able to sleep at nights.”

Читать дальше