“Morning, Harry.” George automatically reached for another filthy glass into which he splashed some of his rotgut whisky.

“How’s things?”

“Things are bloody. Very bloody.” Abbott still ignored me. “Would you have seen young Nick Sandman anywhere, George?” George flickered a glance towards me, then realized that Abbott must be playing some sort of game. “Haven’t set eyes on him since he went to the Falklands, Harry.”

Abbott took the whisky and tasted it gingerly. He shuddered, but drank more. “If you see him, George, knock his bloody head off.” Again George glanced my way, then jerked his gaze back to Abbott. “Of course I will, Harry, of course.”

“And once you’ve clobbered him, George, tell him from me to keep his bloody head down. He is not to show his ugly face in the street, in a pub, anywhere. He is to stay very still and very quiet and hope the world passes him by while his Uncle Harry sorts out the bloody mess he has made.” Some of this was vehemently spat in my direction, but was mostly directed at George. I said nothing, nor did I move.

“I’ll tell him, Harry,” George said hastily.

“You can also tell him, if you should see him, that if he’s got a shooter on his boat, he is to lose it before I search his boat with a bloody metal detector.”

“I’ll tell him, Harry.”

“And if I don’t find it with a detector, then I’ll tear the heap of junk apart plank by bloody plank. Tell him that, George.”

“I’ll tell him, Harry.”

Abbott finished the whisky and helped himself to some more.

“You can also tell Master Sandman that it isn’t the Boer War I’m worried about, but the War of 1812.”

George had never heard of it. “1812, Harry?”

“Between us and America, George.”

“I’ll tell him, Harry.”

Abbott walked to the window from where he stared down through the filth and rain at Sycorax . “I’ll tell the powers-that-be that after an exhaustive search of this den of thieves there was no sign of Master Sandman, nor of his horrible boat.”

“Right, Harry.” The relief in George’s voice that there was to be no trouble was palpable.

Abbott, who had still not looked directly at me, whirled on George and thrust a finger towards him. “And if you do see him, George, hang on to him. I don’t want him running ape all over the bloody South-West.”

“I’ll tell him, Harry.”

“And tell him that I’ll let him know when he can leave.”

“I’ll tell him, Harry.”

“And tell him he’s bloody lucky that no one got killed. One of his bloody bullets went within three inches of Mr Bannister’s pretty head. Mr Bannister is not pleased.”

“I’ll tell him, Harry.”

“They always were rotten shots in that regiment,” Abbott said happily. “Unlike the Rifles of which I was a member. You don’t need to tell him that bit, George.”

“Right, Harry.”

“And tell him his newspaper friend is out of danger, but will have a very nasty bloody headache for a while.”

“I’ll tell him, Harry.”

Abbott sniffed the empty glass of whisky. “How much did you pay for this Scotch, George?”

“It was a business gift, Harry. From an associate.”

“You were fucking robbed. I’m off. Have a nice day.” He left. George closed his eyes and blew out a long breath. “Did you hear all that, Nick?”

“I’m not deaf, Harry.”

“So I don’t need to tell you?”

“No, George.”

“Bloody hell.” He leaned back in his chair and his small, shrewd eyes appraised me. “A shooter, eh? How much do you want for it, Nick?”

“What shooter, George?”

“I can get you a tasty little profit on a shooter, Nick. Automatic, is it?”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about, George.” He looked disappointed. “I always thought you were straight, Nick.”

So did I.

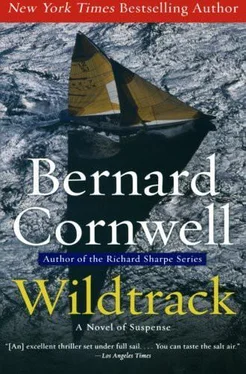

A hot spell hit Britain. The Azores high had shifted north and gave us long, warm days. It was not the weather for an attempt on the St Pierre. In the yachting magazines there were stories about boats waiting in Cherbourg for the bad weather that would promise a fast run at the race, but Wildtrack was not among them. Rita brought me the magazines and a selection of the daily papers. There had been reports of a shooting incident off the Devon coast, a report that received neither confirmation nor amplification and so the story faded away. Bannister’s name was not mentioned, nor was mine. The Daily Telegraph said that a man was being sought in connection with the shooting, but though the police knew his identity he was not being named. The police did not believe the man posed any danger to the general public. England was being hammered at cricket. Unemployment was rising. The City pages reported that Kassouli UK’s half-yearly report showed record profits, despite which, about a week after I’d reached George’s yard, there was a story that Yassir Kassouli was planning to pull all his operations out of Britain. I smelt Micky Harding behind the tale, but after a day or two Kassouli issued a strong denial and the story, like the tale of gunfire off the Devon coast, faded to nothing.

I worked for George Cullen. I mended engines, scarfed in gunwales, repaired gelcoats, and sanded decks. I was paid in beer, sandwiches, and credit. The credit bought three Plastimo compasses.

I mounted one over the chart table, one on the for’ard cockpit bulkhead, and one just aft of the mizzen’s step. I bought the two big anchors off George and stowed them on board. I nagged George to find me a good chronometer and barometer. And every day I tried to phone Angela.

I did not leave messages on the answering machine in Bannister’s house, for I did not want him to suspect that I had reason to trust Angela. I left messages on her home answering machine, and I left messages at the office. The messages told her to phone me at Cullen’s yard. Rita, whose skirts became shorter as the weather became hotter, listened sympathetically to my insistent message-leaving. She thought it was like something out of her magazines of romance.

The messages achieved nothing. Angela was never at her flat, and she never returned the calls. I tried the television company and had myself put through to Matthew Cooper.

“Jesus, Nick! You’ve caused some trouble.”

“I’ve done nothing!”

“Just aborted one good film.” He sounded aggrieved.

“Wasn’t my fault, Matthew. How’s Angela?”

He paused. “She’s not exactly top of the pops here.”

“I can imagine.”

“She keeps saying that the film is salvageable. But Bannister won’t have anything to do with you. He’s issued a possession order for Sycorax .”

“Fuck him,” I said. Rita, pretending not to listen as she buffed her fingernails, giggled. “Will you give Angela a message for me?” I asked.

“She’s stopped working, Nick. She’s with Bannister all the time now.”

“For Christ’s sake, Matthew! Use your imagination! Aren’t good directors supposed to be bursting with imagination? Write her a letter on your headed notepaper. She won’t ignore that.”

“OK.” He sounded reluctant.

“Tell her to find a guy called Micky Harding. He’s probably out of hospital by now.” I gave him Micky’s home and work numbers.

“She’s to tell Micky that he can trust her. She can prove it by calling him Mouse and by saying she knows that Terry was with me on the night. He’ll understand that.”

Matthew wrote it all down.

“And tell her,” I said, “that Bannister’s not to try the St Pierre.”

“You’re joking,” Matthew said. “We’re being sent to film him turning the corner at Newfoundland!”

Читать дальше