“I’ll help,” Micky said grimly, “but I need proof.” He wrinkled his face as he thought. “This Jill-Beth Kirov-like-the-fucking-ballet.

She’s coming back to talk to you?”

“She said so. But I’m planning to move my boat tomorrow. I’m not going to be around to be talked to.”

“You have to move the boat?”

“Bloody hell, yes. Bannister’s threatening to repossess it, and I’ve had enough.”

“No.” Micky shook his head. “No, no, no. Won’t do, Nick. You’ll have to stay there.” He saw my unwilling expression, and sighed.

“Look, mate. If you’re not there, then the American girl won’t talk to you. If she doesn’t talk to you, then we haven’t got any proof.

And if I haven’t got proof then we don’t have a story. Not a bloody dicky-bird.”

“But how does her talking to me provide proof?”

“Because I’ll wire you, you dumb hero. A radio mike under your shirt, an aerial down your underpants, and your Uncle Micky listening in with a tape-recorder.”

“Can you do that?”

“Sure I can do it. I have to get the boss’s permission, but we do it all the time. How do you think we find all those bent coppers and kinky clergymen? But what you have to do, Nick, is go along with it all, understand? Tell Bannister you’d love to navigate his bloody boat. Tell Kassouli you’re itching to help him trap Bannister. String them along!”

“But I don’t want to stay at Bannister’s,” I said unhappily.

“In fact I’ve already told them I’m through with their damned film.”

“Then bloody un-tell them. Eat crow. Say you were wrong.” He was insistent and persuasive; all his world-weariness sloughing away in his eagerness for the story. “You’re doing it for Queen and Country, Nick. You’re saving jobs. You’re staving off some Yankee nastiness. It won’t be for ever, anyway. How long before this American bint turns up with the hundred thousand?”

“I don’t know.”

“Within a month, I’ll wager. So, are you game?” Bannister had not been able to persuade me to stay on to be filmed, nor had Kassouli, nor even the Honourable John, but Micky had done it easily. I said I’d stay. But only till the story broke, and after that I would rid myself of all the rich men into whose squabble I had been unwillingly drawn. “Of course we’ll pay you for the story,” Micky said.

“I don’t want money for it.”

He shook his head. “You are a berk, Nick, you are a real berk.” But I was no longer alone.

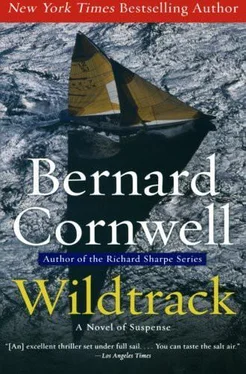

I took the train to Devon next morning. It was raining. Wildtrack had left the river, either gone back to the Hamble marina or else to her training runs. Mystique had also disappeared; probably reclaimed by an angry French charter firm.

But Sycorax was still at my wharf. I had half expected to find her missing, but she was safe and I felt an immense relief.

I limped down to her and climbed into her cockpit. I saw that Jimmy had bolted the portside chainplates into position, ready for the main and mizzen shrouds. I unlocked the cabin padlock and swung myself over the washboards. I lifted the companionway and found the gun still in its hiding place under the engine. If Mulder had been willing to search Mystique , I wondered, why not Sycorax?

I went topsides, but there was no sign of Jimmy. Nothing moved on the river except the small pits of rain. I had the tiredness of time zones, of being dragged by jets through the hours of sleep. I slapped Sycorax ’s coachroof and told her we’d be off soon, that there was not much longer to stay on this river, only so long as it took to trap a coterie of the world’s wealthy people.

There was no beer on board Sycorax , nor anything to eat, so I trudged up to the house only to find that the housekeeper was out.

I knew where she kept a spare house key, so I let myself in and helped myself to beer, bread and cheese from the kitchen. I ate the meal in the big lounge from where I stared out at the rain falling on the river. A grockle barge chugged upstream and I saw the tourists’

faces pressed against the glass as they stared up at Bannister’s big house. Their guide would be telling them that this was where the famous Tony Bannister lived, but in a few weeks, I thought, the newspaper’s scandalous stories would bring yet more people to gape at the lavish house. I supposed the grockle barges must have done good business during my father’s trial.

The sound of the front door slamming echoed through the house.

I turned, expecting to hear the housekeeper go towards the kitchen, but instead it was Angela Westmacott who came into the lounge.

She stopped, apparently surprised at seeing me.

“Good afternoon,” I said politely.

“I thought you’d resigned,” she said acidly.

“I thought we might talk about it,” I said.

“Meaning you need the money?” She was carrying armfuls of shopping which she dropped on to a sofa before stripping off her wet raincoat. “So are you making the film or not?” she demanded.

“I thought we might as well finish it,” I said meekly. I’d planned to go this very afternoon, but, true to the promise I’d made to Micky Harding, I would stay.

“And how is your mother?” Angela asked tartly.

“She’s a tough old bird,” I said vaguely, and feeling somewhat ashamed at being taxed with the lie I’d recorded on the answering machine.

“Your mother sounded quite well when I spoke to her. She was rather surprised at first, but she did eventually say you were in Dallas, though not actually in the house right at that moment.” Angela’s voice was scathing. “I said I’d phone back, but she said I shouldn’t bother.”

“Mother’s like that. Especially when she’s dying.”

“You are a bastard, Nick Sandman. You are a bastard.” I felt immune to her insults because I was no longer in her power.

I had Micky’s newspaper behind me. I turned to watch rainwater trickling down the window. The clouds were almost touching the opposite hillside, which meant the moors would be fogged in. I prayed that Jill-Beth would come to England soon so that I could get the charade of entrapment done, and free myself of all these spoilt, obsessed and selfish people.

A sob startled me. I turned and, to my astonishment, I saw that Angela was crying. She stood at the far end of the long window and the tears were pouring down her face and her thin shoulders were shuddering. I stared, appalled and embarrassed, and she saw me looking at her and twisted angrily away. “All I want to do,” she said in between sobs, “is make a decent film. A good film.”

“You use funny methods to do it,” I said bitterly.

“But it’s like swimming in treacle!” She ignored my words.

“Everything I do, you hate. Everything I try, you oppose. Matthew hates me, the film crew hate me, you hate me!”

“That’s not true.”

She turned like a striking snake. “Medusa?” She waited for a response, but there was nothing I could say. She sniffed, then wiped her eyes on the sleeve of her jacket. “Can’t you see what a good film it could be, Nick? Can’t you, for one moment, just think of that?”

“Good enough to blackmail me? No supplies till I do what you want? If I won’t do everything you want, just as you want it, you threaten to steal my boat!”

“For God’s sake! If I don’t force you, you’d do nothing!” She wailed it at me. She was still crying; her face twisted out of its beauty by her sobs. “You’re like a mule! The bloody film crew spend more time reading the Union regulations than they do filming, Matthew’s frightened of them, you’re so bloody casual, but I’m committed, Nick! I’ve taken the company’s money, their time, their crew, and I don’t even know whether I’m going to be able to finish the film! I don’t know where you are half the time!

Читать дальше