“Girl called Angela Westmacott. She’s a producer on Bannister’s programme.”

Abbott frowned, then clicked his fingers. “Skinny bint, blonde hair?”

“Right.”

“Looks a bit like your ex-wife; starved. How is Melissa?”

“She struggles on.”

“I’ve never understood why men go for those skinny ones.” Abbott paused to drain his pint. “I nicked a bloke once who’d murdered a complete stranger. The victim’s wife asked him to do it, you see, so he bashed the bloke’s head in with a poker. Very messy. She’d promised him a bit of nooky, which is why he did it, and the woman was as scrawny as a plucked chicken. You know what he told me when he confessed?”

“No.”

“He said that it was probably the only chance he would ever get to go to bed with a pretty woman. Pretty? She was about as pretty as a toothpick. And to cap it all she didn’t even give it to him! Told him to sod off when he trotted round with his pecker sharpened.” Abbott stared ruefully across the river. “It was almost the perfect murder, wasn’t it? Having your best-beloved turned off by a stranger.”

The slight stress on ‘perfect murder’ was the second hint that Abbott was not here entirely because he was thirsty. His first hint had been the gentle query why Bannister no longer visited America.

“Perfect murder?” I prompted him.

“My beer glass is empty, Nick, and it’s your round.” I dutifully fetched two pints. “Perfect murder?” I asked again.

“The thing about a perfect murder, Nick, is that we’ll never even know it’s happened. So officially there’s no such thing as a perfect murder. So if you hear about one, Nick, don’t believe in it.” The comments were too pointed to ignore. “Does that mean,” I asked, “that it was an accident?”

“That what was an accident?” Abbott pretended innocence.

“Nadeznha Bannister?”

“I wasn’t there, Nick, I wasn’t there.” Abbott was obscurely pleased with himself. I’d been given a message, though I wasn’t at all sure what or why. Abbott fixed me with his hangdog look. “Have you heard these rumours that someone’s trying to scupper Bannister’s chances of winning the St Pierre?”

“I’ve heard them.”

“And you know what happened two nights ago in the marina?”

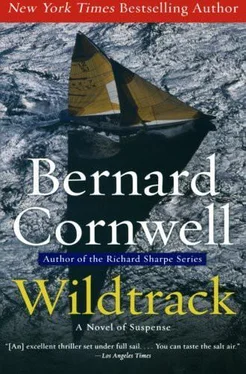

“I heard.” Wildtrack ’s warps had been cut in the dead of the night.

There was a spring tide at the full and, if it had not been for a visiting French yachtsman, Bannister’s boat might have been carried out to sea. Mulder and his crew had been sleeping alongside in the houseboat that had been moved from my wharf and the Frenchman’s shout of warning had woken them just in time. It had all ended safely, and it might all have been dismissed as a trivial incident but for the fact that the warps had been cut. That made it into another attempt at sabotage.

“But clumsy,” Abbott now said. “Very clumsy. I mean, if you wanted to stop a bugger from winning the St Pierre, would you knock his mast off now? Or cut him adrift now? Why not wait till he’s in the race?”

“Does somebody want to stop Bannister winning the St Pierre?” I asked.

Abbott blithely ignored my question. “Kids could have climbed the marina fence and cut the mooring ropes, I suppose.”

“The mast wasn’t wrecked by kids,” I said. “I saw the turnbuckle, and it was sabotage.”

“Whatever a turnbuckle might be,” Abbott said gloomily. “It was probably buggered up by a crew member who just wanted a week off.”

That was a possible answer, I supposed. Certainly, if Melissa was right and Yassir Kassouli did want to end Bannister’s chances of winning the trophy, then the two incidents were very trivial, especially for a man of Kassouli’s reputed wealth. “Are you making enquiries?” I asked Abbott.

“Christ, no! I don’t want to get involved. Besides, as I told you, I’m not crime any more.”

“What are you, Harry?”

“Odds and sods, Nick. General dogsbody.” He sounded bored.

And I was confused. Abbott was sailing very close to the rumours I’d heard, but always sheering off before anything definite was said.

If a message was being given to me, then it was being delivered so elliptically that I was utterly at a loss. I also knew it would be no good demanding elucidation, for Abbott would simply say he was just having an idle chat. “Seen your old man lately?” he asked me now.

“I’ve been busy.”

“You and Jimmy Nicholls, I hear,” Abbott said. Jimmy was helping me to repair Sycorax . “How is he?”

“Coughing.”

“Not long for this world, poor old sod. He shouldn’t smoke so much, should he?” Abbott contemplated putting out his own cigarette, then decided to suck at it instead. He blew smoke at me.

“When’s the big party, Nick?”

He was referring to the party that was to be held at Bannister’s riverside house in the early summer. The party was not just a social affair, but also the occasion on which Bannister would formally announce his entry into the St Pierre. It did not matter that he had already broadcast his intention on nationwide television, he would do it again so that his bid would receive further attention in the newspapers and yachting magazines.

“I hear,” Abbott said, “that Bannister’s introducing his crew at the party?”

“I wouldn’t know, Harry.”

“I just wanted to say to you, Nick, that I do hope you won’t be one of them?”

He was not being elliptical now, far from it. “I won’t be,” I said.

“Because I did hear that Bannister asked you.” I wondered how Abbott had heard, but decided it was simply riverside gossip. I’d told Jimmy, which was the equivalent of printing the news on the front page of the local newspaper. “He did ask,” I said. “I said no, and I haven’t heard anything since.”

“Will he ask again?”

I shrugged. “Probably.”

“Then go on saying no.”

I finished my pint and leaned back. “Why, Harry?”

“Why? Because in an unperverted sort of way, Nick, I’m reasonably fond of you. For your father’s sake, you understand, and because you were stupid enough to win that bloody gong. I wouldn’t want to see you turned into sharkbait. And that boat of Bannister’s does seem to be,” he paused, “unlucky?”

“Unlucky,” I agreed, then wondered if the vague stress Abbott had laid on the word was yet another hint. I tried to force him into a straight answer. “Are you telling me that someone is trying to stop him?”

“Buggered if I know, Nick. Perhaps Bannister’s paranoid. I mean being on the fucking telly must make a man paranoid.” He drained his pint. “I know you’d like to buy me another one, Nick, but the wife has cooked some tripe and pig’s trotters as a special treat, so I’ll be on my way. Remember what I said.”

“I’ll remember.”

I heard his car start and labour up the hill. Out on the river a kid doggedly tacked a Mirror dinghy upstream. Behind it, motoring into the wind, came Mystique . The American girl stood at her tiller and I hoped she might swing across to the pub’s ramshackle pier for a drink, but she stayed on the far bank’s channel instead.

A heron flew past her aluminium-hulled boat and climbed to its nest. Three swans floated beneath the trees. It was a spring evening, full of innocence and charm.

“What did Harry want?” the landlord asked me.

“He was just having a chat.”

“He never does that. He’s a clever bugger, is Harry. Mind you, his golf swing’s lousy. But that’s the only thing Harry wastes time on, believe me.”

I did believe him, and it worried me.

As the days lengthened and warmed, I forgot my worries. I forgot Bannister and Mulder, I forgot the rumours about Nadeznha Bannister’s death and the whispers about sabotage, I even forgot the unpleasantness that had marked my introduction to the television business, because Sycorax mended.

Читать дальше