ELEVEN

MAESTRE DE CAMPO DAMIAN DE ESPLANA proved to be as efficient as his manner had suggested. The evening after Jacques got back to the ship, a galaide layak delivered a dozen kegs of gunpowder to the Nicholas, and with them a Chamorro pilot. A gaunt, taciturn man with a heavily pockmarked face, he was dressed in cast-off European clothing and had a small crucifix on a cord around his neck. In halting Spanish he said that his name was Faasi, and he had a paper to deliver to the captain.

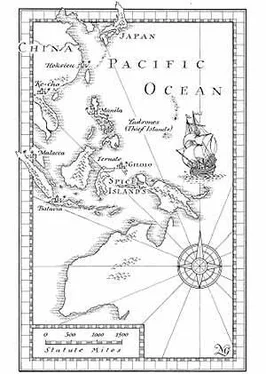

‘Let’s have a look at it,’ said Eaton. It was a crude sketch map of the Ladrones. The fifteen islands, varying in size, stretched away in a chain running northwards. Guahan was marked by name, as were half a dozen of the others. The rest were anonymous.

‘Is that where we find the Governor?’ said Eaton, placing his finger where Esplana had drawn an arrow on the map against one of the farther islands.

The Chamorro stared at the map, but looked blank when Hector translated the question.

‘I don’t think he understands maps,’ said Hector. ‘He probably hasn’t seen one before.’

‘Maug – the island is called Maug, according to what’s written here,’ snapped Eaton.

At the mention of the name, Faasi’s face cleared. He nodded. ‘Yes, Governor at Maug,’ he said.

‘How long to sail there?’ enquired Eaton.

‘Two days, no more,’ answered the Chamorro.

Eaton frowned. It was impossible to judge the scale of the sketch map. But clearly Esplana had made an attempt to draw the islands to their relative sizes.

‘Looks like more than two days’ sail to me,’ he said, ‘unless the ship grows wings.’

‘Best to get started right away, now that we’ve got our powder,’ suggested Arianz.

Eaton treated the Chamorro to a thoughtful glance. Hector guessed the captain was trying to judge whether Faasi was capable of recognizing that the ship wasn’t French.

The quartermaster must have been thinking along the same lines. Laying a hand on the captain’s arm, he drew him to one side and Hector overheard him ask quietly, ‘Do we really need a pilot now that we’ve got a map? We should toss him overboard as soon as we’re off-shore.’

Eaton shook his head. ‘The map’s too vague, and we still need the man to tell us exactly where we lie in wait for the galleon and where we can recruit our new allies.’

Arianz tugged at his earlobe doubtfully. ‘You seem very sure that the natives will fall in with our plan.’

‘That is where the pilot can be even more helpful, though he does not know it yet,’ the captain assured him.

Eaton wasted little time. He weighed anchor at first light, and by early evening the Nicholas was abreast of the northern end of Guahan. Here the Chamorro pilot pointed out the place where the Acapulco Galleon normally paused to transfer her cargo.

‘Ask our pilot if he knows a safe anchorage on the next island along the chain,’ the captain demanded. He had the sketch map in his hand. ‘It’s name is written here as Rota.’

When Hector relayed the question, Faasi’s eyes widened in alarm.

‘He says the people that live there are his enemies. It’s not the place where he was told to bring us.’

Eaton allowed himself a mirthless smile. ‘Then that’s precisely where we pay our next call.’ He ordered the helmsman to maintain course and the crew to shorten sail. Throughout the night the Nicholas crept forward until the rising sun showed Rota’s hills some five miles ahead. The masthead lookout called down to say that he saw no sign of a barrier reef. ‘Make a slow, leisurely approach,’ Eaton ordered the helmsman. ‘The slower, the better. We want our arrival known. Lynch,’ the captain went on, ‘I’m sending you ashore to contact the locals. Our pilot here will go with you.’

‘I doubt he’ll want to.’

Faasi was fingering his little wooden cross nervously and casting worried glances around the ship. Clearly the sight of Rota so close up had rattled him badly.

‘He’ll have no choice,’ said Eaton. He nodded to Stolck and Arianz. The unfortunate pilot was seized and his arms pinioned. He was so shocked that he offered no resistance as his wrists were lashed behind his back.

‘We’ll offer him to our future allies,’ Eaton smirked. ‘When they see you land with him trussed up like a chicken and recognize him as an enemy, they’ll listen to what you have to propose.’

‘And what am I meant to tell them?’

Eaton grinned, a flash of white teeth in his tanned face. ‘Explain that we come as foes of the Spanish and wish to loot the Acapulco Galleon. Say that we’ll supply four musketeers for every sailing craft they can provide for an ambush.’

Hector’s mind raced. Here was an opportunity to get off the Nicholas – and maybe his friends as well. Once ashore, they might be able to take control of their lives.

‘I want my friends with me – Jezreel, Dan and Jacques,’ he said.

‘By all means,’ Eaton was expansive. ‘The striker looks enough of an indio himself. That should reassure the locals.’ He paused. ‘But I wouldn’t want you getting any ideas as soon as you are out of sight. So I’m sending Stolck with you to keep an eye on you.’

OVER THE NEXT few hours, Hector watched the coast of Rota take shape. Low cliffs made a landing difficult. The swells heaved and broke against them, churning into froth. Here and there great lumps of reddish-brown rock had broken off and tumbled into the sea. Beyond the cliff wall the ground swept upwards to the rim of what must be an interior plateau, its edge sharply defined against the puffy white clouds and a blue sky. The cliff tops and hill slopes were smothered with dense green vegetation. Despite the lushness of the landscape and the gentle, summery feel of the air, the place looked inaccessible and mysterious, as if it was guarding secrets. Apart from the flittering swoops of two fairy terns in their brilliant white plumage, there was no sign of life.

The ship hove-to a cable’s length off the first suitable spot to get ashore, a small cove backed by a low cliff. Watched by the crew, Hector and his friends climbed down into the jolly boat. Jezreel had his backsword slung over his shoulder, and Dan chose to bring along his satchel of artist’s materials. Hector and Jacques had nothing more than their sailors’ knives. Only Stolck carried a musket. Arianz had claimed that if the landing party showed too many weapons, they’d scare off the natives, and Hector wondered if the quartermaster was conniving with Eaton to put them deliberately in harm’s way. But Stolck’s presence reassured him. The big Hollander was a close friend of Arianz, and Hector doubted that his countryman would allow him to be abandoned.

The luckless Faasi was passed down like a bundle, his hands still bound. The boat crew bent to their oars and Hector watched the sides of the Nicholas recede. The ship looked weary and sea-worn. Her hull planks were pale grey, bleached by months of sun and salt spray. The tracery of rigging was marred with knots and splices, the ropes whiskery with use. But she was still remarkably seaworthy, a testimony to the ship skills of her crew. She rolled gently, showing the beard of weeds that coated the tar applied so long ago in the Encantadas. Someone had hoisted a home-made French ensign at the mizzen. Hector doubted that the colours of France rippling in the slight breeze meant anything to those on Rota who were watching.

The keel of the little boat crunched on the shingle, and a moment later he climbed over the gunwale, feeling smooth pebbles slither beneath his bare feet. Behind him he heard Jezreel grunt as he lifted the Chamorro pilot out of the boat and set him upright.

Читать дальше