When it came to Hector’s turn he hesitated. ‘You take your turn, just like the rest,’ snapped Eaton. Hector took the rope. It felt slick and sweaty in his hands where others had already gripped it. Half-heartedly he raised his arm and struck, aiming to avoid those areas where Domine’s back was already bruised and cut. The first blow was accurate, but the second too clumsy and must have hit a tender spot, for the Genoese sucked in his breath in a gasp of pain. Ashamed and hoping to soften the third blow, Hector swung the rope, then pulled his arm back just before it struck. The rope’s end flicked like a whip, and to his chagrin the blow split the skin. Behind him he heard Eaton give a low murmur of approval.

After every man had taken his turn, Domine was led away by his friends. They sat him down by the rail. Someone dipped up a bucket of sea water and they began to sponge his back.

The onlookers shuffled away. ‘That should put an end to thievery,’ observed Eaton to no one in particular. For him the matter was closed. But Hector noted Domine’s cronies deliberately turning their backs on the two Hollanders as they walked past. He could only hazard a guess as to how long a common hunger for gold would hold this crew together.

THAT EVENING, if Dan hadn’t been at the ship’s lee rail, the sinking shallop might never have been detected. The Miskito was helping Jacques, dumping ashes from the galley overboard. He emptied the pan and paused to contemplate the fiery orange glow left by the setting sun. Something on the horizon caught his eye. It was shaped like the horns of a crescent, but so small that at first Dan thought it was nothing more than an unusual double wave crest. But when the mark reappeared, lifted on the next swell, he walked aft and drew the helmsman’s attention to what he had just seen. Normally the helmsman wouldn’t have troubled himself to adjust course to investigate. But the object lay almost directly on the ship’s track and he was bored. So he moved the rudder very slightly.

Night had fallen by the time the Nicholas came level with the distant object. It was difficult to see anything more than a patch of deeper shadow. Certainly no one had expected to come across some sort of boat. Yet there it was, barely afloat, the sea washing over its mid-section with each passing swell.

‘What do you make of it?’ Hector asked Dan. The two men stared into the darkness. Beside them half a dozen of the Nicholas ’ crew lined the lee rail. Quartermaster Arianz had ordered the sheets slackened and the yards braced round, so as to take all way off the ship.

‘I have never seen anything like it,’ answered the Miskito. The half-submerged vessel was an unusual shape. Some thirty feet long, it was broad and shallow, and each end curved up prominently. It was impossible to say which was bow and which was stern.

‘Could have been abandoned or broken free of a mooring,’ ventured Jezreel as he joined his friends.

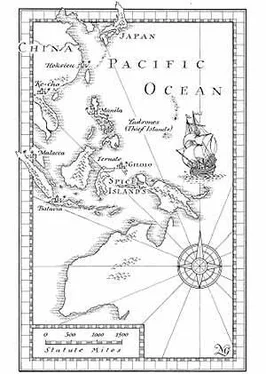

‘But from where?’ asked Hector. ‘We’re too far from land.’

‘That’s not a deep-sea boat,’ observed Dan. ‘It is too small and too lightly built. And there is no shelter for the crew.’ The only structure on the low, wide deck was a hooped cabin of wickerwork, much like a kennel.

‘Why are we halted?’ asked Eaton sourly. The captain had come on deck and not yet noticed the hulk.

‘Some sort of shallop, awash and abandoned,’ said Arianz, gesturing over the side.

Eaton walked to the rail and glanced down. ‘Floating rubbish. It needn’t delay us.’ He turned to Hector. ‘So much for your navigation. Maybe we’re not as distant from land as you’d have us believe.’ He laughed contemptuously.

‘Maybe there’s something worth salvaging?’ suggested the quartermaster.

‘It’s a waste of time,’ snapped Eaton.

The quartermaster ignored him. ‘I’ll send someone to check.’

Dan volunteered for the task. He clambered down the side of the Nicholas , lowered himself into the sea and swam across to the abandoned boat. He pulled himself aboard and Hector saw him bend down to peer into the cabin. A moment later, Dan straightened up and, cupping his hands around his mouth, called out, ‘Throw me a line. There’s someone inside.’

Quickly the derelict shallop was hauled alongside the Nicholas , and the limp figure of a thin, black-haired man, clad only in a loincloth, was hoisted on to the larger vessel. Hector, reaching to help lift the man over the rail, was shocked at how light he was. The stranger weighed no more than a small child. As he was laid on the deck, they could see he was but a living skeleton. His skin had shrunk so that every rib showed starkly. His arms and legs were like sticks, and his body was all hollows and cavities. It was difficult to believe he was still alive. Yet when Hector put his ear against the victim’s chest, he could hear the heart beating.

Someone produced a rag soaked in fresh water, and a dribble was squeezed into the man’s mouth. His eyes stayed closed. He seemed past reviving.

Dan climbed back over the rail, and dropped lightly down on deck. ‘There is nothing else aboard, except for an empty water jar and a straw hat.’

‘Back to your posts, everyone,’ ordered Eaton curtly. ‘We’ve squandered enough time as it is. Cast off the wreck and make sail.’ He turned away and stalked back to his cabin.

‘How long do you think he’s survived?’ asked Jezreel, looking at the wasted figure.

‘Weeks or even months,’ said Hector. ‘Maybe we’ll never find out. I doubt he’ll last the night.’

But when the sun rose next day the castaway, as they now thought of him, was still alive. He lay on the deck, a blanket wrapped around his emaciated body. Only his head was visible. Once or twice his eyelids flickered. His breathing had become noticeably stronger.

‘Where is he from, do you think?’ asked Jacques. He’d prepared a broth to give the patient as soon as he was able to swallow.

‘He’s some sort of Easterner, that’s for sure,’ replied Hector. The man’s skin was yellow-brown, and he had coarse, straight black hair. ‘A Chinaman maybe?’

‘Don’t think so,’ said Jezreel. ‘When I did exhibition fights in London, a few Chinamen worked with the shows. They all had round heads and smooth, chubby faces. This fellow’s jaw is too long, and his face too narrow.’

‘Maybe he can tell us when he comes round,’ said Jacques.

The speed of the castaway’s recovery took everyone by surprise. The very next day he could sit up and was taking an interest in his surroundings. But his expression gave no clue as to what he was thinking. The crew tried talking to him in every language they could muster. When that failed, they used gestures, hoping to learn where he came from. But he didn’t respond and remained silent, impassively observing everything going on aboard the Nicholas . Some of the crew believed he was a mute by birth, others that his terrible ordeal had destroyed his power of speech.

‘I wonder what he is thinking?’ said Jacques two mornings later. The castaway had not moved from his spot, and sat on his blanket with a bowl of soup in his hand. He accepted it from the Frenchman without a smile or nod of thanks. From time to time he raised the bowl to his lips and sipped, but continued to stare at his surroundings.

‘He can speak. I’m sure of that,’ Hector said quietly.

There was something disquieting about the stranger’s behaviour, Hector felt. He scarcely moved his head, but the brown eyes, so dark they were almost black and sunk deep in their sockets, were never still. His gaze darted from one place to the next, observing the crew at work, looking up at the sky and sails, following whatever was going on aboard ship. It was as if he was trying to make sense of his situation with a guarded intelligence, yet hiding the reason why.

Читать дальше