Roberto Saviano - Gomorrah - A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Roberto Saviano - Gomorrah - A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

There’s no real difference between movie audiences in the land of the Camorra and elsewhere. Cinematographic references everywhere create mythologies of imitation. If elsewhere you may like Scarface and secretly identify with him, here you can be Scarface, but you have to be him all the way.

In the land of the Camorra, people are also passionate about art and literature. Sandokan had an enormous library in his villa bunker, with dozens of volumes, all on two topics: the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, and Napoléon Bonaparte. Sandokan was attracted to the Bourbon state’s importance, bragging that his ancestors were officers in southern Italy, the Terra di Lavoro. He was fascinated by the genius of Bonaparte, who rose from a low military rank to conquer half of Europe; he saw similarities to his own life, for he’d started at the bottom and was now generalissimo of one of the most powerful clans in Europe. Sandokan, who had once been a medical student, preferred to pass his time in hiding painting religious icons and portraits of Napoléon and Mussolini. They’re still for sale today, in Caserta shops that are above suspicion: extremely rare holy images, Sandokan’s own face inserted in place of Christ’s. He also liked reading epics. Homer, the Arthurian legends, and Walter Scott were his favorites. It was his love of Scott that inspired him to baptize one of his numerous children with the grandiloquent, proud name of Ivanhoe.

But the names of the sons always bear a trace of the passions of the father. Giuseppe Misso, boss of the Sanità neighborhood clan, has three grandchildren: Ben Hur, Jesus, and Emiliano Zapata. When on trial, Misso always assumed the attitude of political leader, conservative thinker, and rebel; he recently wrote a novel, I leoni di marmo, “The Marble Lions.” Several hundred copies were sold in a few weeks in Naples. Told with a mangled syntax but in a furious style, it is the story of Naples in the 1980s and 1990s, the story of the boss’s formation, his emergence as lone warrior against the Camorra of rackets and drugs, in defense of a chivalrous but vaguely defined code of robbery and theft. He was arrested many times in his long criminal career, and each time he was found with books by Julius Evola and Ezra Pound.

Augusto La Torre, the boss of Mondragone, is a student of psychology, an avid reader of Carl Jung, and an expert on Sigmund Freud. A glance at the titles of the books he requested in prison reveals a lengthy bibliography of scholars of psychoanalysis, and in court, quotations of Lacan are interwoven with his reflections on the Gestalt school of psychology. A knowledge the boss utilized in his rise to power, an unexpected managerial and military weapon.

Even one of Paolo Di Lauro’s most loyal men is a lover of culture: Tommaso Prestieri produces many neo-melodic singers and is a connoisseur of contemporary art. Many bosses are art collectors. Pasquale Galasso’s villa housed a private museum with about three hundred antiques; the jewel of the collection was the throne of the Bourbon king Francis I. And Luigi Vollaro, known as ‘o califfo or the caliph, owned a painting by his favorite artist, Botticelli.

The police were able to arrest Prestieri because of his love of music. He was caught at the Teatro Bellini in Naples when he went to hear a concert while a fugitive. After his sentencing, Prestieri declared, “In art I am free, I don’t need to be released from prison.” Painting and song offer equilibrium and impossible serenity to an unlucky boss such as Prestieri, who has lost two brothers, both killed in cold blood.

*The lowest-ranking Mafioso.—Trans.

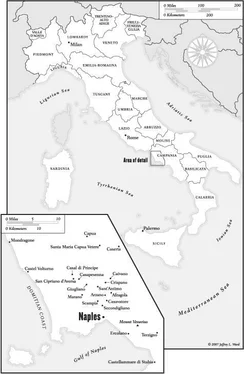

ABERDEEN, MONDRAGONE

Augusto La Torre, the psychoanalyst boss, was one of Antonio Bardellino’s favorites. He had taken his father’s place when he was young, becoming the sole leader of the Chiuovi clan, as it was called in Mondragone, which ruled in northern Caserta, southern Lazio, and along the Domitian coast. The La Torre clan had sided with Sandokan Schiavone’s enemies, but their management and business savvy, the only elements powerful enough to alter conflictual relationships among Camorra families, eventually reconciled them to the Casalesi, with whom they worked while still maintaining their autonomy. Augusto didn’t come by his name by chance. La Torre family tradition was to name the firstborn after a Roman emperor. But in this case they inverted history; instead of Augustus being followed by Tiberius, Tiberius was father to Augustus.

Scipio Africanus’s villa near Lake Patria, Hannibal’s battles at Capua, and the unassailable might of the Samnites, the first warriors in Europe to attack the Roman legions and then flee to the mountains— these stories are legends in local Camorra families, who consider themselves linked to the distant past. The clans’ historical fantasies clashed with the widespread image of Mondragone as the mozzarella capital of Italy. My father used to stuff me full of mozzarelle from Mondragone, but it was impossible to decide which area’s mozzarella was the best. The flavors were too diverse: the light, sickly sweetness of Battipaglia, the heavy saltiness of Aversa, or the purity of Mondragone. But the Mondragone mozzarella masters had a way to tell. A good mozzarella leaves an aftertaste, what country folk call ‘o ciato ‘ e bbufala or buffalo breath. If there’s no buffalo aftertaste, the mozzarella isn’t any good. I liked to stroll back and forth on the Mondragone wharf, one of my favorite summer destinations before it was demolished. A tongue of reinforced concrete, boat moorings built out over the sea. A useless, unused construction.

Mondragone suddenly became the place for all the kids around Caserta and the Pontine Marshes who wanted to emigrate to the UK. Emigration, the chance of a lifetime, a way to finally get out, but not as a waiter, a scullery boy in a McDonald’s, or a bartender paid in pints of dark beer. They went to Mondragone to try to make contacts with the right people, who could get you a good rent and an in with employers. In Mondragone there were people who could get you a job in insurance or real estate, and who helped the desperate, chronically unemployed find a decent contract and respectable work. Mondragone was the door to Great Britain. Starting in the late 1990s, having a friend in Mondragone all of a sudden meant you’d be valued for what you’re worth, without needing recommendations or connections. A rare thing, impossible in Italy, especially in the south. Around here, you always need a protector, someone who can at least get your foot in the door, if not the rest of you. Presenting yourself without a protector is like showing up without arms and legs. With something missing. But in Mondragone they’d take your résumé and see whom to send it to in the UK. Your skills mattered and, even more, the way you used them. But only in London or Aberdeen. Not in Campania, the most provincial of the provinces of Europe.

My friend Matteo decided to give it a try, to leave once and for all. He’d graduated cum laude and was tired of doing internships, of supporting himself working construction sites. He’d put aside some money and got the name of a guy in Mondragone who would help him line up some job interviews in Britain. I went with him. We waited for hours at the beach where Matteo’s contact had told him to meet. It was summer. Mondragone’s beaches are invaded by vacationers from all over Campania, the ones who can’t afford the Amalfi coast or a summer rental on the shore, so they commute from the hinterland. Till the mid-1980s mozzarelle were sold on the beach, in wooden pails overflowing with boiling buffalo milk. The bathers ate them with their hands, the milk dripping all over. Kids would lick their hands, salty from the sea, then take a bite. But no one sells them anymore, now it’s grissini and coconut slices. Our contact was two hours late. When he finally showed up, tanned and wearing only a skimpy bathing suit, he explained that he’d eaten breakfast late, so had gone for a swim late and had dried himself off late. That was his excuse—it was the sun’s fault. He took us to a travel agency. That was all. We thought we were going to meet some big middleman, but instead we were merely introduced at an agency, and not a particularly elegant one at that. Not one of those agencies with hundreds of brochures, just an ordinary hole-in-the-wall kind of place. But you needed a local contact to access their services; to anybody just walking in, it seemed like a normal travel agency. A young woman asked Matteo for his résumé and told us the first available flight to Aberdeen. That’s where they were sending him. They handed him a list of businesses where he could go for an interview, and for a small fee they’d even set up appointments with the people doing the hiring. Never had a temp agency been so efficient. Two days later we boarded the plane for Scotland, a quick and affordable trip from Mondragone.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.