Roberto Saviano - Gomorrah - A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Roberto Saviano - Gomorrah - A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I have never for one instant felt pious, yet Don Peppino’s words resounded with something beyond the religious. He created a new method that reestablished religious and political speech. A faith in being able to bite into reality and not let go until you rip it to pieces. A language capable of tracing the scent of money.

We tend to think that money doesn’t smell, but that’s true only when it is in the emperor’s hands. Before it ends up between his fingers, pecunia olet —money does indeed smell. Like a latrine. Don Peppino toiled in a land where money carries a scent, but only for a moment—the instant in which it is extracted, before it becomes something else, before it can become legitimate. Odors we recognize only when our noses brush against what smells. Don Peppino Diana realized that he had to keep his face close to the ground, on people’s backs and eyes, that he couldn’t pull away if he wanted to keep seeing and pointing the finger, if he wanted to understand where and how business wealth accumulates, and how the killings and arrests, the feuds and silences, begin. He had to keep his instrument—the word—the only tool that could alter the reality of his time, on the tip of his tongue. And this word, incapable of keeping silent, was his death sentence. His killers did not pick a date by chance. March 19, 1994, was the feast of San Giuseppe, his name day. Early morning. Don Peppino was in the church meeting room near his study. He had not yet donned his priestly robes, so it was not immediately clear who he was.

“Who is Don Peppino?”

“I am.”

His final answer. Shots echoed in the nave. Two bullets hit him in the face, others pierced his head, neck, and hand, and one hit the bunch of keys on his belt. They had shot from close range, aiming at his head. A shell lodged between his jacket and his sweater. Don Peppino was getting ready to say the first mass of the day. He was thirty-six years old.

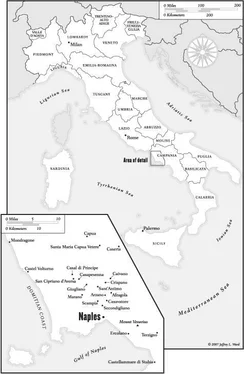

Renato Natale, Casal di Principe’s Communist mayor, was one of the first to race to the church, where he found the priest’s body still on the floor. Natale had been elected only four months earlier. It was no coincidence; they wanted to make that body fall during his very, very brief political tenure. He was the first Casal di Principe mayor to make fighting the clans a top priority. He had even resigned from the town council in protest because he felt it had been reduced to merely rubber-stamping decisions that were made elsewhere. The carabinieri once raided the house of Gaetano Corvino, a town councilman, finding all the top clan managers assembled while Corvino was at a council meeting at the town hall. On the one side town business, on the other business via the town. Doing business is the only reason to get out of bed in the morning; it tugs on your pajamas and gets you up and on your feet.

I had always watched Renato Natale from afar, as you do those people who unwillingly become symbols of some idea of commitment, resistance, and courage. Symbols that are almost metaphysical, unreal, archetypal. I felt a teenager’s embarrassment observing his efforts to set up clinics for immigrants and speak out against the Casalese Camorra families’ power and their cement and waste-management operations during the dark years of the feuds. They had approached him, threatened his life, told him that if he didn’t stop, his family would be made to pay for his choices, but he carried on speaking out in every way he could, even putting up posters around town that revealed what the clans had decided and done. The more persistent and courageous he was, the more his metaphysical protection grew. One would have to know the political history of this region to understand the real weight of terms such as commitment and will.

Since the law regarding Mafia infiltration went into effect, sixteen town councils in the province of Caserta have been dissolved, five of them twice: Carinola, Casal di Principe, Casapesenna, Castelvolturno, Cesa, Frignano, Grazzanise, Lusciano, Mondragone, Pignataro Maggiore, Recale, San Cipriano, Santa Maria la Fossa, San Tammaro, Teverola, Villa di Briano. When candidates opposing the clans manage to win in these towns, overcoming the vote-trading and economic strategies that constrain every political alliance, they have to reckon with the limits of the local administrations, extremely tight funds, and total marginality. They have to demolish, brick by brick, to face off multinational companies with small-town budgets, and rein in enormous firing squads with local troops. Such as in 1988 when the Casapesenna town councilor Antonio Cangiano opposed clan infiltration of certain contracts. They threatened him, tailed him, and shot him in the back, right in the piazza, right in front of everyone. If he wasn’t going to let the Casalesi clan get ahead, then the Casalesi wouldn’t let him even walk. They confined Cangiano to a wheelchair. The alleged perpetrators were acquitted in 2006.

Casal di Principe is not a town under Mafia attack in Sicily, where opposing the criminal business class is difficult, but where your actions are flanked by a parade of video cameras, famous and soon-to-be-famous journalists, and swarms of national anti-Mafia officials who somehow manage to amplify their role. Here everything you do remains within narrow perimeters and is shared with only a few. I believe that it is precisely within this solitude that what could be called courage is forged: a sort of armor that you don’t think about, that you wear without noticing. You carry on, do what you have to do—the rest is worthless. Because the threat isn’t always a bullet between the eyes or a ton of buffalo shit dumped on your front doorstep.

They take you slowly, one layer at a time, till you find yourself naked and alone and you start believing you’re fighting something that does not exist, a hallucination of your brain. You start believing the slander that marks you as a malcontent who takes it out on successful people, whom you label Camorristi out of frustration. They play with you the way they do with Pick Up sticks. They pick up all the sticks without ever making you move, so that in the end you’re all alone, and loneliness drags you by the hair. But you can’t allow yourself that feeling here; it’s a risk—if you lower your guard, you won’t be able to understand the mechanisms, symbols, choices. You risk not noticing anything anymore. So you have to draw on all your resources. You have to find something that fuels the stomach of your soul in order to carry on. Christ, Buddha, civil commitment, ethics, Marxism, pride, anarchy, the fight against crime, cleanliness, persistent and everlasting rage, southernness. Something. Not a hook to hang on. More like a root, something underground and unassailable. In the useless battle in which you’re sure to play the role of the loser, there is something you have to preserve and know. You have to be certain it will grow stronger while your wasted energy tastes of folly and obsession. I have learned to recognize that root in the eyes of those who have decided to stare certain powers in the face.

Giuseppe Quadrano and his men, who were allied with Sandokan’s enemies, were immediately suspected of Don Peppino’s murder. There were also two witnesses: a photographer who was there to wish Don Peppino well, and the church sexton. As soon as word got out that police suspicions were directed toward Quadrano, the boss Nunzio De Falco, known as ‘o lupo or the Wolf, called the Caserta police and asked for a meeting to clarify some questions concerning one of his affiliates. As a result of territorial divisions of power among the Casalesi, De Falco was in Granada, Spain. Two Caserta officers went to meet him there. The boss’s wife picked them up at the airport and drove into the beautiful Andalusian countryside. Nunzio De Falco was waiting for them not in his villa in Santa Fe, but in a restaurant where most of the customers were probably insiders ready to react if the police did anything rash. The boss immediately explained that he had called them to offer his version of the story, a sort of interpretation of a historical event rather than a denunciation or accusation. A clear and necessary preamble so as not to besmirch the family’s name and authority. He could not start collaborating with the police. Without beating around the bush the boss declared that it had been the Schiavone family—his rivals—who had killed Don Peppino. They had done it to make suspicion fall on the De Falcos. The Wolf said that he would never have given the order to kill Don Peppino Diana because his own brother Mario was close to him. The priest had even tried to free Mario from the Camorra system and had succeeded in keeping him from becoming a clan manager. It was one of Don Peppino’s major accomplishments, but De Falco used it as an alibi. Two other affiliates, Mario Santoro and Francesco Piacenti, backed up the boss’s theory.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.