Roberto Saviano - Gomorrah - A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Roberto Saviano - Gomorrah - A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The judges ordered the seizure of three concessionaries and numerous companies connected to the distribution and sale of milk, all accused of being controlled by the Casalesi. The milk companies were registered under false names on their behalf. Cirio and Parmalat dealt directly with the brother-in-law of Michele Zagaria, the Casalesi clan regent in hiding for a decade, in order to obtain special client status, which they won above all through commercial deals. Cirio and Parmalat brands gave their distributors special discounts—from 4 to 6.5 percent, rather than the usual 3 percent—as well as various production awards, so supermarkets and retailers also received price reductions. In this way the Casalesi achieved widespread acquiescence for their commercial predominance. And where pacific persuasion and common interest didn’t work, violence did: threats, extortion, destruction of transport vehicles. They beat up their competitors’ drivers, plundered their trucks, and burned their depots. The fear was so widespread that in the areas controlled by the clans it was impossible not only to distribute but even to find someone willing to sell brands other than those imposed by the Casalesi. In the end, consumers paid the price: with a monopoly and a frozen market, there was no real competition, and retail prices were uncontrollable.

The big deal between the national milk companies and the Camorra came to light in the fall of 2000, when Cuono Lettiero, a Casalesi affiliate, began collaborating with the law and discussing the clans’ commercial ties. The guarantee of a constant rate of sale was the most direct and automatic way of obtaining bank guarantees—the dream of every big business. In this scenario, Cirio and Parmalat were officially the “offended parties”—the victims of extortion—but investigators became convinced that the mood was relatively relaxed and that the behavior of both the national companies and the local Camorristi was mutually beneficial.

Cirio and Parmalat—at least their management at the time—never reported suffering from clan interference in Campania. Not even in 1998, when a Cirio official was attacked in his home near Caserta; he was brutally beaten with a stick in front of his wife and nine-year-old daughter because he hadn’t obeyed clan orders. No rebellion, no charges filed. The certainty of the monopoly was better than the uncertainty of the market. The money to maintain the monopoly and take possession of the Campania market had to be justified on the company balance sheet. But in the country of creative financing and the decriminalization of false accounting, this was not a problem. False invoicing, false sponsorships, and false year-end awards for milk sales resolved any bookkeeping problems. To this end, nonexistent events have been paid for since 1997: the Mozzarella Festival, Music in the Piazza, even the Feast of San Tammaro, patron saint of Villa Literno. As a token of esteem for its employees, Cirio even financed the Polisportiva Afragolese, a sports club run by the Moccia clan, as well as an extensive network of music, sports, and recreation centers, demonstrating the “public spiritedness” of the Casalesi. Cirio stated that it had been forced to do so as part of a protection racket and insisted that it was the victim. (Subsequent to these investigations and the financial scandals that ensued, both Cirio and Parmalat filed for bankruptcy. Both companies have been reconstituted and continue to trade under completely new management teams.)

The power of the clan has grown extensively in recent years, extending to eastern Europe: Poland, Romania, and Hungary. Poland was where Francesco Cicciariello Schiavone, Sandokan’s cousin, the squat, mustachioed boss and a principal Camorra figure, was arrested in 2004. He was wanted for ten homicides, three kidnappings, nine attempted homicides, numerous violations of arms laws, and extortion. They nabbed him as he was grocery shopping with his twenty-five-year-old Romanian companion Luiza Boetz. Cicciariello was going by the name of Antonio and seemed like an ordinary fifty-one-year-old Italian businessman. But his companion must have sensed that something was amiss when, in an attempt to throw off the police bloodhounds, she had to make a long and tortuous train journey to join him in Krosno, near Kraków. They tailed her across three borders, followed her by car to the outskirts of the Polish city, and finally stopped Cicciariello at the supermarket checkout; he had shaved his mustache, straightened his curly hair, and lost weight. Cicciariello had moved to Hungary, but con-tinued to meet his companion in Poland, where he had big business interests: animal farms, land purchases, deals with local businessmen. The Italian representative of SECI, the Southeast European Cooperative Initiative for Combating Trans-Border Crime, had reported that Schiavone and his men frequently went to Romania and had started important dealings in Barlad in the east, in Sinaia in the center, and in Cluj in the west, as well as along the Black Sea. Cicciariello Schiavone had two lovers: Luiza Boetz and Cristina Coremanciau, also Romanian. In Casale, word of his arrest “because of a woman” was like a slap in his face. The headline of one local paper seemed to sneer at him: “Cicciariello arrested with his lover.” In truth both of his lovers were crucial to his business as they were in fact managers who handled his investments in Poland and Romania. Cicciariello was one of the last Schiavone family bosses to be arrested. In twenty years of power and feuds, many Casalesi clan leaders and supporters had been locked away. All the investigations against the cartel and its branches were grouped together in the Spartacus maxi-trial, named after the rebel gladiator who had attempted the greatest insurrection Rome had ever known on this very same land.

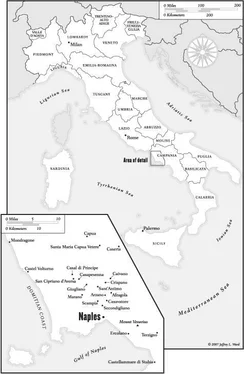

I went to the courthouse in Santa Maria Capua Venere on the day of the sentencing. I was expecting video crews and photographers, but there were only a few, and only from local newspapers and TV stations. But police and carabinieri were everywhere. About two hundred of them. Two helicopters were hovering low over the courthouse, the noise of the propellers pounding in everyone’s ears. Bomb detection dogs, police vehicles. The mood was extremely tense. And yet the national press and TV crews were absent. The media was totally ignoring the biggest trial—in terms of the number of accused and convictions requested—of a criminal cartel. Experts refer to the Spartacus trial by a number: 3615, the number assigned to the investigation in the general register, with around thirteen hundred DDA inquiries beginning in 1993, all stemming from Carmine Schiavone’s testimony.

The trial lasted seven years and twenty-one days, for a total of 626 hearings. The most complex Mafia trial in Italy in the last fifteen years. Five hundred witnesses took the stand, in addition to twenty-four government witnesses, six of whom were defendants. Ninety files were deposited: acts, sentences from other trials, documents, and wiretaps. Almost a year after the 1995 blitz, the offspring investigations of Spartacus also started up: Spartacus 2 and Regi Lagni, related to the renovation of the Bourbon canals, which hadn’t been properly restored since the eighteenth century. According to the accusations, the clans had piloted the renovation project for years, generating contracts worth millions. Rather than putting the money toward the canals, they channeled it into their construction businesses, which subsequently became extremely successful throughout Italy. There was also the Aima trial, related to the swindling in the famous produce collection centers, where the European community destroyed surplus production, providing subsidies to the farmers. The clans dumped trash, iron, and construction waste into the huge craters intended for the produce. But first they had it all weighed as if it were produce. And obviously they collected the subsidies while the fruit of their lands continued to be sold. One hundred and thirty-one orders of seizure were issued regarding companies, lands, and agricultural businesses, amounting to hundreds of millions of euros. Two soccer clubs were also seized: Albanova, which competed in the C2 league, and Casal di Principe.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.