How could I have been so stupid?

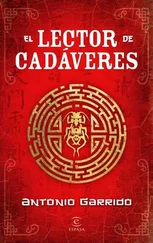

Since their confrontation, they hadn’t spoken another word, except for Ming to mention that Emperor Ningzong himself was awaiting their arrival.

Ningzong, the Heavenly Son, the Tranquil Ancestor. Very few were allowed even to kneel before him, let alone look at him directly. Only his most trusted advisers were allowed to approach him, only his wives and children could ever touch him, and only his eunuchs were permitted to converse with him. He spent his days inside the Great Palace, protected by its imposing walls from the rest of the city. Shut up in his golden cage, the Supreme Herald’s time was taken up with interminable receptions, ceremonies, and rites that, according to Confucian strictures, would never change. It was well known that his position was one of great responsibility and sacrifice.

Now that Cí was about to cross the threshold, he was utterly intimidated. The group went through the entrance, and a world of sumptuous wealth opened up before Cí’s eyes. Beautifully carved stone fountains were situated throughout the gardens, and he caught a glimpse of a leaping roebuck. Iridescent-blue peacocks roamed free. Streams trickled between clumps of peonies and wide, old trees. The columns, eaves, and balustrades of the palace buildings glinted gold, vermilion, and cinnabar-scarlet. Cí marveled at the roofs with their extravagant cornices curling skyward. The buildings were perfectly aligned on a north-south axis and had the presence of an enormous soldier so confident of his strength that he would spurn any offer of protection. Yet there were still seemingly countless ranks of sentries standing guard on either side of the entrance that separated the palace from the city.

The hushed group came to a halt at the steps of the Reception Pavilion—the first of the palace buildings, which stood between the Palace of Cold and the Palace of Heat. A stout man with a soft, wrinkled face waited impatiently for them beneath a glazed-tile portico; his cap identified him as the venerable Kan, Minister of Xing Bu, the much-feared Councilor for Punishments. As they came closer, Cí saw the man had one eye missing, and the remaining eye blinked nervously.

A sullen-looking official carried out the formal introductions. Following the bows of greeting, he asked the group to follow him.

They walked along a passageway that passed through several galleries and auditoriums. In one gallery, snow-white porcelain vases contrasted against purple lacquer walls. Another glowed so green it resembled a jade mine. After this they came to an impressive pavilion, where the official leading them stopped.

“Honored experts,” he said, indicating the unoccupied throne behind them, “salute Emperor Ningzong.”

They all prostrated themselves before the throne as if the emperor were really there. This ritual complete, Councilor Kan took the floor, climbing up onto a dais and scanning the room with his one eye. There was a touch of terror in the man’s countenance.

“As you already know, you have been brought here on account of a truly shocking matter. A situation that I suspect will require you to summon more instinct than wit. It is a truly monstrous matter. I don’t know if the criminal we are facing should be counted as a human being or some vermin aberration of nature. Whatever the case may be, your task is to try and apprehend this abomination.”

He descended the dais and led them to a door where two colossal guards bore large axes. Cí couldn’t help but be dazzled by the ebony doorway, its lintel wrought with depictions of the Ten Kings of Hell. Stepping through, he was hit by the unmistakable smell of rotting flesh. Each person in the group was given a piece of cotton soaked in camphor to hold to his nose.

They arranged themselves around a bloody bulk in the middle of the room. Horror immediately registered on everyone’s face. The cloth was blood-soaked, particularly in the area of the chest and neck.

The head matron of the palace stepped forward at a signal and uncovered the corpse, drawing gasps. Beneath the sheet lay a mutilated, headless body. One member of the group vomited, and everyone else recoiled. Everyone, that is, except Cí.

Undaunted, he scanned the body of what appeared to have once been a woman but now looked more like a partially devoured animal. The tender flesh had been pitilessly defiled, the head severed completely, and bits and stumps of trachea and esophagus hung from the neck like a pig’s entrails. The feet had both been cut off at the ankles. Two grievous wounds stood out among the many on the torso: The first, above the right breast, was a deep, messy cavity that looked as though some beast had sunk its maw in and tried to eat out the lungs. The second was even more atrocious: a triangular incision straight across the navel and then down on both sides over the groin that left only a bloody gap. The entire pubic area had been removed in some strange ritual. They were informed that the missing parts of the body, including the head, were yet to be found.

The sight filled Cí with sadness. He noticed, in a stark and poignant contrast to the violence done on the body, the woman’s hands, which were very delicate, and a hint of her perfume, still discernible even amid the awful stink of decomposition.

Kan read out a preliminary report based on the matron’s examination. It included a rough idea of the corpse’s age (thirty or so), remarks on the state of the breasts and nipples (small and flaccid), and a note about the velvet texture of the pale, downy hair. The report also mentioned that the corpse had been found fully clothed, disposed of on a street near the Salt Market. There was a final speculation as to what kind of animal might have been capable of wreaking such havoc on a body: a tiger, a dog, or perhaps a dragon, it said.

Cí wasn’t convinced of the value of the matron’s comments. She was probably good at many things, but he seriously doubted she had much acumen when it came to corpses. The problem was, of course, that Confucianism forbade men from touching the dead bodies of women, and no one would disobey the law. They’d have to base their findings on those of the matron, and that was that.

With the reading of the report concluded, Kan asked those in attendance for their verdicts.

The prefecture judge went first, stepping forward and asking the matron to turn the body so he could look at the back. The rest of the group drew closer. The back itself was pale and free of wounds, the waist fairly thick, and the buttocks flabby and smooth. The judge began circling the corpse, tugging pensively at his goatee. He then went over to the clothes the corpse had been found in and held up a simple linen smock of the kind worn by servants. The prefecture judge scratched his head and addressed Kan.

“Councilor for Punishments,” he said, “such a loathsome crime…In my opinion, it would be irrelevant for me to talk about the type and number of wounds. Given the strangeness of the wounds, I am in clear agreement with my colleagues on the idea that an animal might be responsible.” He stopped and meditated on his next remark. “But the wounds also lead me to think that we might be dealing with the work of a sect: the followers of the White Lotus, Manichaeans perhaps, Nestorian Christians, or maybe the Maitreya Messianists. Driven by some abominable desire, the killers cut off the head and feet in some bloody ceremony and then allowed some beast to devour the lung. The motives could be varied, though, given how twisted the mind of a killer has to be: an initiation ritual, a punishment, a demon offering, an attempt to remove some elixir contained in a gland or an organ.”

Kan nodded and seemed to weigh the judge’s words for a moment before inviting Ming to take the floor.

Читать дальше