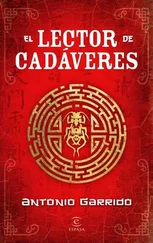

“He already benefited from our generosity,” pointed out the elder master, “when we let him join the academy.”

Ming turned back to the committee members.

“If you don’t feel you can trust him, place your trust in me.”

Aside from the four professors who were trying to see Ming dismissed, the rest of the committee eventually voted for Cí to stay—under Ming’s strict supervision. They also agreed that the tiniest of infractions from the boy would lead to immediate dismissal of both Cí and Ming.

When Ming informed Cí, he could barely believe it.

Ming said that, from now on, Cí would be his personal assistant. He’d no longer sleep in the dormitory but would move up to Ming’s private apartments, with access to the private library whenever he wanted. He’d continue to attend morning classes, but during the second half of the day he’d assist Ming in his investigations. Cí was overwhelmed; he genuinely couldn’t understand why Ming had such faith in him or why the committee had approved these privileges.

The academy became a kind of paradise for Cí, and afternoons and evenings were the best. This was when he’d go to Ming’s office and immerse himself in the books Ming had recovered from the Faculty of Medicine before its closure. The more he read, though, the more Cí realized how poorly organized the valuable information was. He came up with the idea of systematizing this chaos by compiling new volumes, organized according to ailments.

Ming thought it was a wonderful idea. He presented it to the committee and managed to win funding for the acquisition of more sources and to remunerate Cí.

Cí put his all into the project. To begin with, he compiled and organized information from the medical texts. As the months went by, he began to include some of his own ideas in the new volumes. He’d write at night, after Ming had gone to bed. In the yellowish lantern light, he described how to examine a corpse; in his opinion, an exhaustive contextual understanding was fundamental, but he also argued strongly for perfectionism, even in the smallest tasks. He created a step-by-step procedure, which involved beginning the examination of a corpse at the crown of the head, working down along the cranial sutures, the birth line in the hair, and down the forehead to the eyes—including lifting up and checking under the eyelids, ignoring the idea that the spirit might escape this way. Then one proceeded to the throat; the chest if dealing with a man or the breasts if a woman; the heart area; the uvula and navel; and the pubic region, including the penis, scrotum, and testicles, or the vagina. Finally, the legs and feet and the arms and hands were to be examined, not forgetting the toenails and fingernails. Once the body was turned over, the entirety of the corpse’s back side required an equal amount of care; every part should be pressed on scrupulously to check for marks left by inflammation or beatings.

Ming didn’t quite know how to react when he read the first pages. Much of what Cí had written, especially when it came to the forensic examinations, was clearer and more precise than many of the treatises in the library. And some of the procedures and experiences it detailed were new even to Ming, as were the innovative proposals on the use of surgical implements and the cold box, which Cí had dubbed the “conservation chamber,” one of which he had acquired and modified for the long-term conservation of body organs.

Cí barely saw the other students. Perhaps it was his family’s ghosts that urged him to work himself to the bone, but he didn’t feel he needed much else in his life. He didn’t have any friends, or companions even, but the isolation didn’t bother him. He did his work as best as he could and was hard on himself. He had eyes only for his books, and his heart was set on achieving his dreams.

Ming kept reminding Cí of the importance of legal understanding, too.

“Remember, determining the causes of death won’t be your sole function. What happens if a man is found to have been killed by several other men? Or, even worse, what happens if he dies over the course of a few days? How will you tell if his death was due to the wounds he received or a previous condition?”

While Cí knew how to classify deaths according to the instruments that had caused them, he was surprised when Ming taught him how the time elapsed since death was calculated. Wounds caused by blows from hands or feet would be certain to cause death within a period of ten days, Ming explained. In the case of wounds from any kind of weapon, including bite wounds, the time limit would be set at twenty days. Scalding and burns went up to thirty days, the time also allotted to gouged eyes, split lips, and broken bones.

Ming explained that if the deceased died within the amount of time that corresponded to the type of wound, it was determined to be caused by the wound, but if death came after the prescribed period, it was not due to that wound, and the person who inflicted it could not be accused of murder.

When Cí said he thought it was more sensible to treat each case individually, Ming shook his head.

“We have laws for a reason. Hasn’t your rebellious streak gotten you in enough trouble?”

Cí hung his head to signal he had nothing more to add. But he wasn’t so sure about the laws. Yes, they were surely crafted with good intentions, but the rules had also allowed someone like Gray Fox to become an Imperial official. The thought of it made Cí’s stomach hurt, but he continued with his work, speculating about what exactly had become of Gray Fox.

Winter went by in a flash, but when spring arrived, Cí was in turmoil.

He began waking up from nightmares so vivid he would search for Third in the darkness. He’d then spend the rest of the night trembling, terrified and alone, feeling the absence of his family. Feng came to his mind at points, and he wished he could be under his wing again.

One afternoon he decided to seek solace and company at the Palace of Pleasure.

The girl he chose was kind to him; Cí would even have gone so far as to say she was sweet. Her caresses didn’t avoid his burn marks, and her lips did things he’d barely imagined possible. In exchange for a few qián she gave him brief respite.

He began going back to see the same girl every week. And one cloudy evening as he was leaving, he ran into Gray Fox, who was drinking and being rowdy with a moronic little retinue but who sobered up when he saw Cí. The scar on Gray Fox’s lip from Cí’s punch had altered his face considerably. Cí made a dash for the door, but Gray Fox and the others got there first; they held Cí’s arms as Gray Fox laid into him.

And because he couldn’t feel the blows and didn’t pretend to feel pain, they hit him harder and harder, until he could no longer move.

He woke up at the academy. Ming was mopping his brow with a cool cloth, showing as much care as a mother would show her child. Cí could barely move, and his eyes were swollen almost closed. Blackness swallowed him again. When he woke again, Ming was still with him.

Ming told him he’d been out for three days; a girl who seemed to know Cí had reported his situation. Ming and several students had brought him back to the academy.

“According to her, you were attacked by strangers. At least that’s what I’ve been telling people here.”

Cí tried to get up, but Ming told him to rest. The healer who had been to see him had recommended a couple of weeks’ rest, at least until his fractured ribs were better. Cí’s first thought was that he’d be missing important classes, but Ming told him not to worry and took his hand with all the sweetness of a “flower.”

Читать дальше