Philippa Gregory - Changeling

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Philippa Gregory - Changeling» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: Simon & Schuster, Inc., Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Changeling

- Автор:

- Издательство:Simon & Schuster, Inc.

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:9780857077332

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Changeling: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Changeling»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Changeling — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Changeling», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘My lord,’ he said, trying for dignity. ‘May I ask you now where we are going?’

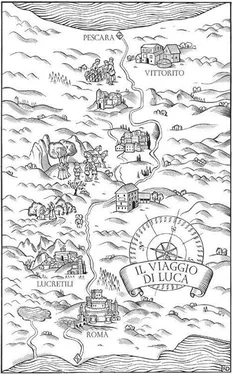

‘You’ll know soon enough,’ came the terse reply. The river ran like a wide moat around the tall walls of the city of Rome. The boatman kept the little craft close to the lee of the walls, hidden from the sentries above, then Luca saw ahead of them the looming shape of a stone bridge and, just before it, a grille set in an arched stone doorway of the wall. As the boat nosed inwards, the grille slipped noiselessly up and, with one practised push of the oar, they shot inside, into a torch-lit cellar.

With a deep lurch of fear Luca wished that he had taken his chance with the river. There were half a dozen grim-faced men waiting for him and, as the boatman held a well-worn ring on the wall to steady the craft, they reached down and hauled Luca out of the boat, to push him down a narrow corridor. Luca felt, rather than saw, thick stone walls on either side, smooth wooden floorboards underfoot, heard his own breathing, ragged with fear, then they paused before a heavy wooden door, struck it with a single knock and waited.

A voice from inside the room said ‘Come!’ and the guard swung the door open and thrust Luca inside. Luca stood, heart pounding, blinking at the sudden brightness of dozens of wax candles, and heard the door close silently behind him.

A solitary man was sitting at a table, papers before him. He wore a robe of rich velvet in so dark a blue that it appeared almost black, the hood completely concealing his face from Luca, who stood before the table and swallowed down his fear. Whatever happened, he decided, he was not going to beg for his life. Somehow, he would find the courage to face whatever was coming. He would not shame himself, nor his tough stoical father, by whimpering like a girl.

‘You will be wondering why you are here, where you are, and who I am,’ the man said. ‘I will tell you these things. But, first, you must answer me everything that I ask. Do you understand?’

Luca nodded.

‘You must not lie to me. Your life hangs in the balance here, and you cannot guess what answers I would prefer. Be sure to tell the truth: you would be a fool to die for a lie.’

Luca tried to nod but found he was shaking.

‘You are Luca Vero, a novice priest at the monastery of St Xavier, having joined the monastery when you were a boy of eleven? You have been an orphan for the last three years, since your parents died when you were fourteen?’

‘My parents disappeared,’ Luca said. He cleared his tight throat. ‘They may not be dead. They were captured by an Ottoman raid but nobody saw them killed. Nobody knows where they are now; but they may very well be alive.’

The Inquisitor made a minute note on a piece of paper before him. Luca watched the tip of the black feather as the quill moved across the page. ‘You hope,’ the man said briefly. ‘You hope that they are alive and will come back to you.’ He spoke as if hope was the greatest folly.

‘I do.’

‘Raised by the brothers, sworn to join their holy order, yet you went to your confessor, and then to the abbot, and told them that the relic that they keep at the monastery, a nail from the true cross, was a fake.’

The monotone voice was accusation enough. Luca knew this was a citation of his heresy. He knew also, that the only punishment for heresy was death.

‘I didn’t mean . . .’

‘Why did you say the relic was a fake?’

Luca looked down at his boots, at the dark wooden floor, at the heavy table, at the lime washed walls – anywhere but at the shadowy face of the softly spoken questioner. ‘I will beg the abbot’s pardon and do penance,’ he said. ‘I didn’t mean heresy. Before God, I am no heretic. I meant no wrong.’

‘I shall be the judge if you are a heretic, and I have seen younger men than you, who have done and said less than you, crying on the rack for mercy, as their joints pop from their sockets. I have heard better men than you begging for the stake, longing for death as their only release from pain.’

Luca shook his head at the thought of the Inquisition, which could order this fate for him and see it done, and think it to the glory of God. He dared to say nothing more.

‘Why did you say the relic was a fake?’

‘I did not mean . . .’

‘Why?’

‘It is a piece of a nail about three inches long, and a quarter of an inch wide,’ Luca said unwillingly. ‘You can see it, though it is now mounted in gold and covered with jewels. But you can still see the size of it.’

The Inquisitor nodded. ‘So?’

‘The abbey of St Peter has a nail from the true cross. So does the abbey of St Joseph. I looked in the monastery library to see if there were any others, and there are about four hundred nails in Italy alone, more in France, more in Spain, more in England.’

The man waited in unsympathetic silence.

‘I calculated the likely size of the nails,’ Luca said miserably. ‘I calculated the number of pieces that they might have been broken into. It didn’t add up. There are far too many relics for them all to come from one crucifixion. The Bible says a nail in each palm and one through the feet. That’s only three nails.’ Luca glanced at the dark face of his interrogator. ‘It’s not blasphemy to say this, I don’t think. The Bible itself says it clearly. Then, in addition, if you count the nails used in building the cross, there would be four at the central joint to hold the cross bar. That makes seven original nails. Only seven. Say each nail is about five inches long. That’s about thirty-five inches of nails used in the true cross. But there are thousands of relics. That’s not to say whether any nail or any fragment is genuine or not. It’s not for me to judge. But I can’t help but see that there are just too many nails for them all to come from one cross.’

Still the man said nothing.

‘It’s numbers,’ Luca said helplessly. ‘It’s how I think. I think about numbers – they interest me.’

‘You took it upon yourself to study this? And you took it upon yourself to decide that there are too many nails in churches around the world for them all to be true, for them all to come from the sacred cross?’

Luca dropped to his knees, knowing himself to be guilty. ‘I meant no wrong,’ he whispered upwards at the shadowy figure. ‘I just started wondering, and then I made the calculations, and then the abbot found my paper where I had written the calculations and—’ He broke off.

‘The abbot, quite rightly, accused you of heresy and forbidden studies, misquoting the Bible for your own purposes, reading without guidance, showing independence of thought, studying without permission, at the wrong time, studying forbidden books . . .’ the man continued, reading from the list. He looked at Luca: ‘Thinking for yourself. That’s the worst of it, isn’t it? You were sworn into an order with certain established beliefs and then you started thinking for yourself.’

Luca nodded. ‘I am sorry.’

‘The priesthood does not need men who think for themselves.’

‘I know,’ Luca said, very low.

‘You made a vow of obedience – that is a vow not to think for yourself.’

Luca bowed his head, waiting to hear his sentence.

The flame of the candles bobbed as somewhere outside a door opened and a cold draught blew through the rooms.

‘Always thought like this? With numbers?’

Luca nodded.

‘Any friends in the monastery? Have you discussed this with anyone?’

He shook his head. ‘I didn’t discuss this.’

The man looked at his notes. ‘You have a companion called Freize?’

Luca smiled for the first time. ‘He’s just the kitchen boy at the monastery,’ he said. ‘He took a liking to me as soon as I arrived, when I was just eleven. He was only twelve or thirteen himself. He made up his mind that I was too thin, he said I wouldn’t last the winter. He kept bringing me extra food. He’s just the spit lad really.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Changeling»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Changeling» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Changeling» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.