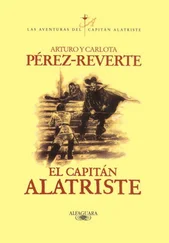

Arturo Perez-Reverte - Captain Alatriste

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Arturo Perez-Reverte - Captain Alatriste» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Captain Alatriste

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Captain Alatriste: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Captain Alatriste»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Captain Alatriste — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Captain Alatriste», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"Underhanded dog!" grunted Alatriste.

"Well, by God," the other responded. "You surely didn't think I would ask your permission."

Again the two swordsmen stood studying each other. The Italian ended that with a twirl of his blade, Alatriste responded with another, and again each cautiously raised his sword, and steel brushed steel with a faint metallic ching, before they lowered their swords again.

"Devil take it," the Italian sighed hoarsely. "There is no end to this." He began to back away from the captain, very slowly, his sword held horizontally between them. Only when he was safely away, almost at the corner post, did he turn his back.

"Incidentally," he called as he was fading into the shadows, "the name is Gualterio Malatesta. Did you hear? And I come from Palermo. I want that burned into your brain when I kill you!"

The man I had shot was still whimpering for confession. His shoulder was shattered, and splinters of his clavicle were protruding from the wound. Very soon, the Devil would be well served.

Diego Alatriste gave him a quick, impersonal look, went through his purse, as he had earlier with the dead man's, and then came over and knelt beside me. He did not thank me, or say any of the things one might expect would be said when a thirteen-year-old boy has saved a man's life. He simply asked if I was all right, and when I replied that I was, he tucked his sword beneath one arm and, putting the other around my shoulders, helped me to my feet. His mustache brushed my cheek for an instant, and I saw that his eyes, paler than ever in the light of the moon, were observing me with strange intensity, as if he were seeing me for the first time.

The dying man moaned again, again pleading for confession. The captain turned back, and I could see him thinking.

"Run over to San Andres," he said finally, "and fetch a priest for this miserable fellow."

I stared at him, hesitating; it seemed to me that I had glimpsed that bitter, ill-humored grimace on his lips.

"His name is Ordonez," he added. "I recognize him from Flanders."

Then he picked up the pistols and started off. Before I obeyed his orders, I went back to the carriage guard on the corner to look for his cape, then ran after him and handed it to him. He tossed it over one shoulder and lightly touched my cheek—with a show of affection unusual in him. And he kept looking at me with the same expression he had had when he asked if I was all right. Half embarrassed, half proud, I felt a drop of blood from his wounded hand drip onto my face.

IX. THE STEPS OF SAN FELIPE

A few days of calm followed that sleepless night. But as Diego Alatriste continued to refuse to leave the city, or hide, we lived in a perpetual state of alert; we might as well have been in a campaign. Staying alive, I discovered, can be much more tiring than letting oneself be killed, and requires all five senses. The captain slept more during the day than he did at night, and at the least sound—a cat on the roof, or the creak of wood on the stairs—I would awaken in my bed to see him in his nightshirt, sitting up in his, with the vizcaina or a pistol in his hand.

After the skirmish at the Gate of Lost Souls, he had tried to send me back to my mother for a while, or to the house of a friend. I told him that I had no intention of abandoning our camp, that his fate was mine, and that if I had been capable of getting off two pistol shots, I could fire

off another twenty if the occasion demanded. A position I reinforced by expressing my determination to run away from any place he might send me. I do not know whether Alatriste was grateful for my decision, for I have told you that he was not a man given to revealing his feelings. But at least I had made my point. He shrugged and did not bring up the matter again.

In fact, the next day I found a fine dagger on my pillow, recently purchased on Calle de los Espaderos: damascened handle, steel cross-guard, and a long, finely tempered blade, slim and double-edged. It was one of those daggers our grandfathers called a misericordia, for it was used to put caballeros fallen in battle out of their misery. That was the first weapon I ever possessed, and I kept it, with great fondness, for twenty years, until one day in Rocroi I had to leave it buried between the fastenings of a Frenchman's corselet. Which is actually not a bad end for a fine dagger like that one.

All the time that we were sleeping with one eye open, and jumping at our own shadows, Madrid was ablaze with celebrations occasioned by the visit of the Prince of Wales, an event that was by now official. There were days of cavalcades, soirees in the Alcazar Real, banquets, receptions, and masked balls, all topped off with a festival of "bulls and canes" in the Plaza Mayor that I remember as one of the most outstanding spectacles of its kind ever seen in our Madrid of the Austrias. The finest caballeros in the whole city—among them our young king—took part, wielding lances or pikes and pitting themselves against Jarama bulls in a glorious display of grace and courage. This fiesta of the corrida was, as it continues to be today, the favorite celebration of the people of Madrid—and of no few other places in Spain. The king himself, and our beautiful Queen Isabel—though a daughter of the great Henri IV, the Bearnais, and through him Elizabeth of France—were very fond of them. My lord and king, the fourth Philip, was known to be an elegant horseman and a fine shot, an aficionado of the hunt and of horses—once, in a single day, killing three wild boars by his own hand but losing a fine mount in the process. His sporting skills were immortalized in the paintings of Don Diego Velazquez, as well as in poems by many authors and poets such as Lope de Vega or Francisco de Quevedo. These lines by Don Pedro Calderon de la Barca are from his popular play La banda y la flor:

Shall I tell what gallant horseman

Decked out in high boots and spurs,

Arms at a pleasing angle, the hand

Held low to rein in his steed,

Cape neatly arranged, back

Ramrod-straight, eyes alert,

Trotted elegantly through the streets

Beside the carriage of the queen?

I have already said elsewhere that in his eighteenth or twentieth year, Philip was—and would be for many years—congenial, fond of the ladies, elegant, and beloved of his people. Ah, our good, mistreated Spanish people, who always considered their kings to be the most just and magnanimous on earth, even when their power was on the decline; even though the reign of the previous king, Philip the Third, had been brief, but with time enough to be calamitous left in the hands of an incompetent and venal favorite; and even though our young monarch, a consummate horseman, if lethargic and incapable in affairs of government, was at the mercy of the accomplishments and disasters—and there were many more of the latter—of the Conde, and later Duque, de Olivares.

The Spanish people—or at least what is left of them— have changed a great deal since then. Their pride and admiration for their king was followed by scorn; enthusiasm by acerbic criticism; dreams of greatness by deep depression and general pessimism.

I well remember"—and I believe this happened during the festival of the bulls honoring the Prince of Wales, or perhaps a later one—that one of the beasts was so fierce that it could not be hamstrung or slowed. No one—not even the Spanish, Burgundian, and German guards ornamenting the plaza—dared go near it. Then, from the balcony of the Casa de la Panaderia, our good King Philip, calm as you please, asked one of the guards for his harquebus. Without losing a whit of royal composure or making any grandiose gestures, he casually took the gun, went down to the plaza, threw his cape over his shoulder, confidently requested his hat, and aimed so true that lifting the weapon, firing it, and dropping the bull were all one and the same motion.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Captain Alatriste»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Captain Alatriste» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Captain Alatriste» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.