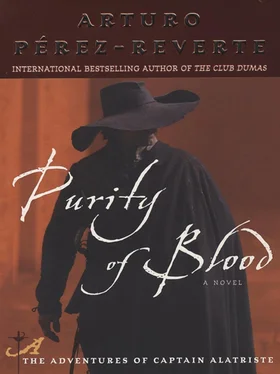

Arturo Pérez-Reverte - Purity of Blood

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Arturo Pérez-Reverte - Purity of Blood» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Purity of Blood

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Purity of Blood: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Purity of Blood»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Purity of Blood — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Purity of Blood», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But that morning in Madrid, in ’23, Rocroi existed only in the dark pages of Destiny, and two decades would pass before that fateful encounter. Our king was young and gallant, Madrid was the capital of two worlds, the old and the new, and I myself was a beardless youth. I crouched impatiently at the crack in a cupboard, waiting for the answer to the question the captain had posed: What plan had don Vicente de la Cruz and his sons, through the good offices of don Francisco de Quevedo, come to present? As the grieving father prepared to answer, a cat jumped through the window and slipped between my legs. I tried, quietly, to brush it away, but it refused to leave. Then I moved too brusquely, and a broom and a tin dust bin crashed to the floor. And when I looked up, horrified, the door had been flung open and the elder son of don Vicente de la Cruz was standing before me, dagger in hand.

“I believed you to be inflexible in regard to purity of blood, don Francisco,” said Captain Alatriste, when we three were alone. “I never imagined that you would place your neck in a noose for a family of Jew-turned-Christian conversos. ”

I glimpsed a smile of affectionate indulgence beneath the captain’s mustache. Seated at our table, wearing the face of a man with few friends, Señor de Quevedo was dispatching the jug of wine that until that moment no one had touched. After reaching an accord with the captain, don Vicente de la Cruz and his sons had left.

“Everything has its…charm,” the poet murmured.

“I have no doubt. But if your much-loved Luis de Góngora catches scent of this, you should prepare to be lambasted. His sonnet will drop you to your knees.”

“A pox on him.”

But it was true. In a time when hatred of Jews and heretics was considered an indispensable component of faith—only a few years earlier, the aforementioned Lope, as well as good don Miguel de Cervantes, had crowed over the expulsion of the Moors—don Francisco de Quevedo, who prided himself on being an old Christian from Santander, was not exactly noted for his tolerance of anyone whose purity of blood was dubious. On the contrary, he often used that theme when aiming darts at his adversaries—and especially don Luis de Góngora, to whom he attributed Jewish blood.

Why should Greek be a tongue you debase? and not Hebrew? We know you master that, it is as clear as the nose on your face.

The great satirist liked to intersperse such compliments with allusions to Góngora’s sodomy, as he did in a certain famous sonnet that concludes,

Your legs are worse than my poor two. I limp, it’s true, but they do not go the places your third leg leads you to.

Yet here he was, getting his own hands dirty: don Francisco Gómez de Quevedo y Villegas, he of the habit of Santiago and proven family purity, lord of la Torre de Juan Abad, scourge of Judaizers, heretics, sodomites, and assorted Latinate court poets, risking life and honor, plotting nothing less than to violate the sanctity of a cloister in order to aid a family of Valencian conversos. Even I, at my tender age, recognized the terrible implications.

“A pox on him, by Christ,” the poet repeated.

I suppose that any sane man would be swearing—in Greek, even Hebrew, both languages that don Francisco was familiar with—had he found himself in Quevedo’s starched white collar. And Captain Alatriste, who was not in Quevedo’s gorget, but faced ruin enough in his own, was well aware of that.

The captain had not moved from his place against the wall throughout the conversation with our visitors, and his thumbs were still hooked over his belt. He had not shifted position even when Jerónimo de la Cruz returned to the room, dagger in hand, leading me by the ear. Alatriste merely ordered the man to release me, in a tone that inspired my captor, after only an instant’s hesitation, to obey. As for me, the awkward moment past, I was huddled in a corner, still red with embarrassment, trying to pass unnoticed. It had taken a certain effort to convince the father and sons that although disobedient, I was a prudent lad and could be trusted. Don Francisco himself had to speak for me. But the beans had been spilled—I had heard everything—and don Vicente de la Cruz and his sons would have to put their faith in me. Although when it came down to it—as the captain clarified very deliberately, casting cold, intimidating looks at each of the three in turn—this was no longer a situation in which they could offer an opinion or have a choice. That declaration was followed by a long and weighty silence, after which my involvement was not questioned again.

“They are good people,” Quevedo said finally. “And blood or no blood, no one can accuse them of not being good Catholics.” He paused in search of further justification. “And when we were in Italy, don Vicente performed a number of services for me. It would have been wicked not to hold out a hand to him.”

Captain Alatriste nodded his understanding, and beneath his military mustache I could see the same irrepressible smile.

“All that you say is well and good,” the captain acknowledged. “But I press my point about Góngora. After all, Your Mercy is constantly dwelling on his Semitic nose and his aversion to the flesh of the pig. You remember when you wrote,

“No white shows in your hair, so old Christian you cannot be: sonofa something, no question there, but son of pure blood? A mockery.”

Don Francisco smoothed his mustache and goatee, half pleased that the captain remembered his verses, and half annoyed by the bantering way he recited them.

“By the good Christ, Alatriste, what a good—and, I might add, badly timed—memory you have.”

Alatriste burst out laughing, unable to contain himself any longer, which did not improve the poet’s humor.

“I can just imagine what your enemy will write,” said the captain, beating a dead horse, holding his fingers as if he were writing on air.

“You say, don Francisco, I am a filthy Jewish pig, while you dance to the tune of a lively Hebrew jig…

“What do you think?”

Don Franciso’s face grew even more dour. Were it not Diego Alatriste speaking, his tormentor would have tasted steel some time ago.

“Bad, and with very little flair,” was all he said, dispiritedly. “Those lines could, in fact, have been written by that Cordovan sodomite, or that other friend of yours, the Conde de Guadalmedina, whose behavior as a caballero I do not contest, but who as a poet is the mortification of Parnassus. As for Góngora, that puerile asshole, that proparoxytonic, euphistic versifier, that dabbler in vortices, tricliniums, promptuaria, and vacillating Icaruses, that shadow on the sun and eructation of the wind…he is the last thing that worries me now. I do fear, however, that I have brought you into a bad business.” He gripped the jug of wine more tightly and took another swig, glancing in my direction. “And the lad.”

The lad—that is, I—was still in the corner. The cat had strolled past me three times, and I had made every effort to get in a good kick, with little success. I saw that Alatriste, too, was looking at me, and he was no longer smiling. Finally he shrugged his shoulders.

“The lad got himself into it,” he declared calmly. “As for me, do not concern yourself.” He pointed to the pouch of gold escudos in the center of the table. “They have paid, and that eases all cares.”

“Perhaps.”

The poet did not seem convinced, and Alatriste’s lips again twisted with irony.

“What the devil, don Francisco. It is a little late for regrets, now that you’ve already got me dressed for the ball.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Purity of Blood»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Purity of Blood» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Purity of Blood» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.