Despite it being a cold and rainy day, over thirty-thousand people came out to greet their arrival.

The first-class passengers were allowed to disembark first. Among them, the White Star Line’s managing director, Bruce Ismay, who somehow found a seat on a lifeboat during the confusion. By his side were two U.S. senators, William Smith from Michigan and Francis Newlands from Nevada, who had come with a subpoena requiring him to testify in a formal inquiry. Since Monday morning, Ismay had sent out numerous wireless messages from the Carpathia explaining what had happened, covering his tracks and trying to get ahead of the blame.

Newspapers ran headlines like:

Margaret stepped off the gangway into the throng of waiting families. Ahead of her was John Jacob Astor’s young wife, Madeline, who rushed by a band of reporters and disappeared into an automobile. Days later, John’s body would be pulled from the sea with twenty-five hundred dollars in his coat pocket.

Margaret stood for a moment under the pier’s bright spotlights watching the tearful reunions take place all around. Seeing she was alone, the reporters rushed over with cameras.

“There have been rumors of an infection on the ship,” one reporter said. “Can you confirm this?”

“I can’t deny it.”

“With such loss of life, how were you able to beat the odds?” a different reporter asked.

“That’s easy. Typical Brown luck,” Margaret replied. “We’re unsinkable.”

May 21, 1912

LIGHTOLLER

They had just returned from a short recess.

It was the twelfth day of testimony in the British Board of Trade’s inquiry into the disaster, the second day for Charles Lightoller, who had already answered close to a thousand questions.

The British hearings took place in the London Scottish Drill Hall, an old but spacious building with room for an audience of well over a hundred, and where every sound seemed to carry an echo. Lord Mersey was the commissioner presiding over the hearings, but it was Thomas Scanlan, representing the National Sailors’ and Firemen’s Union, who currently had the floor.

It had been over a month since the Titanic sank and the press was still hungry for answers.

Over three hundred bodies had been recovered from the sea in the days after the sinking, some still alive and moaning even though they looked dead. Word going around the newsrooms was these lingering infected had been quieted before being loaded on to one of the recovery ships, and then quickly transferred to an undisclosed military facility where they were cut open and examined—the findings of which remained classified.

Lightoller had testified in the U.S. inquiry in late April. He and many of his peers had come under scrutiny by the harsh eyes of a headstrong Senator who sought to place blame on his employers. Lightoller had kept most of his story a secret, telling only the necessary details. He would certainly not tell them the most gruesome things he had experienced, fearing they might irrationally charge him with a crime.

After his testimony concluded, he was allowed to return to his native England, where he was delighted to experience the simple comforts of home, and to see his wife and two boys. Prior to his embarking on the Titanic , Sylvia had brought forth the idea of having a third child, which Lightoller was eager to get to work on.

Settling back into normal life wouldn’t come easy though, as not a night went by that he didn’t think about the Titanic; about the many who had needlessly perished; about Murdoch and Moody and Smith; about all those that he had slayed, like Elise Brennan and the young boy. But most of all, he thought about the infant he had kept warm and safe in his arms until the Carpathia arrived, the beautiful, nameless princess, and wished as Captain Smith had, that she would live a long and healthy life.

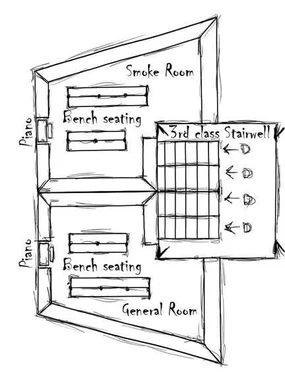

Lightoller sat back behind the witness stand and took a sip of water from a glass vile. To his right was a large model drawing of the Titanic from the starboard side—to the right of the model, an even larger chart of the North Atlantic indicating the Titanic’s route and last known position.

Before the break, Thomas Scanlan had been drilling him on such things like the loading of the lifeboats, his knowledge of ice warnings, and the absence of binoculars in the crow’s nest. Scanlan’s scathing assault was almost as vicious as some aboard the Titanic . Lightoller thought it immoral that he wasn’t given an axe to defend himself.

Still.

He would give them what they want, play the part they assigned him, walk the high wire in their circus act, if doing so would get him beyond the Titanic and back to living.

Anything to get back to living.

SCANLAN:Can you tell us at what speed the ship was going when you left the bridge at ten o'clock?

LIGHTOLLER: About twenty-one and a half knots.

SCANLAN: The speed was taken down, I understand, in the log?

LIGHTOLLER: Yes, the scrap log.

SCANLAN: In view of the abnormal conditions, and of the fact that you were nearing ice at ten o'clock, was there not a very obvious reason for going slower?

LIGHTOLLER: Well, I can only quote you my experience throughout the last twenty-four years, and I have never seen the speed reduced.

SCANLAN: Is it not quite clear that the most obvious way to avoid ice is by reducing speed?

LIGHTOLLER:Not necessarily the most obvious. It is one way. Naturally, if you stop the ship you will not collide with anything.

SCANLAN: Am I to understand, even with the knowledge you have had coming through this disaster, at the present moment, if you were placed in the same circumstances, you would still bang on at twenty-one and a half knots an hour?

LIGHTOLLER: I do not approve of the term banging on.

SCANLAN: I mean drive ahead.

LIGHTOLLER: That looks like carelessness, you know. It looks as if we would recklessly bang on and slap her into ice regardless of anything. Undoubtedly, we should not do that.

SCANLAN: What I want to suggest to you is that it was recklessness, utter recklessness, in view of the abnormal conditions, and in view of the knowledge you had from various sources that ice was in your immediate vicinity, to proceed at twenty-one and a half knots?

LIGHTOLLER: Then all I can say is that recklessness applies to practically every commander and every ship crossing the Atlantic Ocean.

SCANLAN: But is it careful navigation in your view?

LIGHTOLLER: It is ordinary navigation, which embodies careful navigation.

SCANLAN: First Officer William Murdoch followed you on watch, did he not?

LIGHTOLLER: Yes.

SCANLAN: Was he made aware of the conditions?

LIGHTOLLER: He was.

SCANLAN: But you’ve said before that Murdoch wasn’t on the bridge at the time the ship hit the iceberg.

LIGHTOLLER: Is that a question?

SCANLAN: Consider it as such.

LIGHTOLLER: To my knowledge, Murdoch wasn’t on the bridge. It was his watch, yes. But I believe he was still below decks with Officer Lowe.

SCANLAN: Who was on the bridge at the time of the collision?

Читать дальше