“Until what? ” said Bruce Ismay. He came into the navigating room wearing a large coat over his pajamas. “What are you saying, Thomas? The Titanic cannot sink.”

“But she can,” said Andrews. “And, regrettably, I’m certain that she will.”

Ismay bit his lip and relaxed his posture.

“How long do we have?” asked Smith.

Andrews studied the blueprints, doing the mathematical calculations in his head, and then said, “Maybe an hour. Two, if we’re lucky.”

“It appears you’re going to get your headlines after all, Mr. Ismay,” said Smith. Then he ordered Boxhall to calculate the ship’s exact position so they could send out a distress call.

Ismay and Andrews sulked away in silence.

Alone again with Wilde, Smith picked back up on their prior conversation.

“How are you feeling?”

“I believe I have a fever,” Wilde replied.

Smith studied the chief officer. “I can’t say for certain. But if you were bitten, then you are most likely infected. How is your hand?”

Wilde pulled up the left sleeve again. His hand had turned purple and swollen considerably. “I suppose it doesn’t much matter now, does it? If we’re all going to die, that is.”

“Perhaps, though I intend to spare as many as possible. I’d appreciate it if you would go to your quarters and remain there. For the sake of others. I hope you understand.”

“Whatever I can do to help, in these, my final moments.”

“Thank you, Henry. It’s been a pleasure.”

“Thank you, sir.”

Moments after Wilde left, Murdoch and Lowe entered the wheelhouse. Smith explained the grim fate of the ship, while Murdoch caught him up on the spread of the infection.

“The best we can hope for is that someone is nearby and responds to our call,” said Smith. “For now, begin preparing the lifeboats for loading. And please protect yourselves. Where are Lightoller and Moody?”

“We split off. Have they not returned?”

“No, they have not.”

Murdoch shrugged. “Well, I’m sure they’ll come around soon, sir.”

Ten minutes later, Captain Smith entered the wireless room with the Titanic’s estimated position in hand. He handed the coordinates to Harold Bride.

“Send the distress call.”

Bride slipped the piece of paper in front of Jack Phillips, who was wearing the wireless set.

“What call should I send?” asked Phillips.

“The regulation international call for help. That’s all.”

Smith left the wireless room and walked along the boat deck, inspecting the officers as they readied the lifeboats. Murdoch was on the starboard side uncovering lifeboat number seven.

“Where is Wilde?”

“He had something to tend to,” Smith replied.

“Should we swing out the boats?”

“Yes, go ahead. Then begin loading, women and children first. I take it you’re still armed?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Good. See to it that no infected make their way on to the lifeboats. I’ll tell the others the same.”

ANDREWS

From the moment he realized the ship would founder, Thomas Andrews, by his own calculations, had at best a couple of hours left on this earth. How he was going to die was still to be determined, but he had decided right away that he would not take a seat on one of the lifeboats, even if the chance were offered to him.

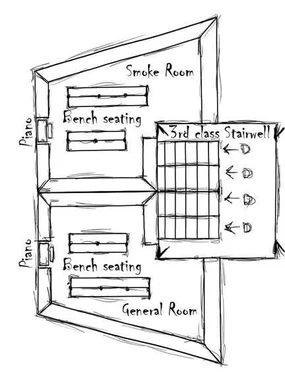

He knew the math better than anyone.

There were over twenty two hundred passengers on board and only twenty lifeboats. The fourteen standard lifeboats could carry roughly seventy passengers each. The two emergency cutters and four collapsible boats could hold around forty-five. Assuming the loading of the boats went smoothly (which didn’t seem promising since Captain Smith had cancelled the lifeboat drill), a little over half of the passengers might survive.

And at least a thousand would perish.

Of course, the infection also played a part in trimming the numbers. After multiple attempts, the virus had proved impossible to contain, and in a short time had spread to nearly all areas of the ship. How many lives had it already claimed, and how many more would succumb to the unthinkable illness before the sea put its cold stamp on it for good?

Andrews sat behind the desk in his stateroom sobbing for the ones who couldn’t be saved, and for his own personal family, praying they find the strength to carry on without him. He thought of his wife Helen. They wouldn’t make it to their four-year anniversary in June; their marriage was coming to an unexpected end tonight. Nor would he be around to help raise two-year-old Elizabeth. In fact, she’d grow up never knowing him at all, or not remember the short time where she had—from this point forward he would only exist to her in photographs, stories, and melancholy newspaper articles.

Thus, he sat with his head in his hands wondering how best to make use of his final moments. He could remain closed within his room sulking in regret and waiting for the water to crash through the walls and take him under, or he could die with some small measure of dignity.

Andrews left his stateroom and began helping the crew warn passengers of the coming doom. There was no use lying to people to avoid a panic, the panic had already long come.

He walked from one end of the ship to the other, up and down decks, knocking on doors and urging people to put on their lifebelts and begin heading up to the boat deck. Some people did exactly as he asked, while others either completely ignored him or couldn’t grasp the severity of the situation. Many stayed hidden in their rooms, afraid to come out. Everyone was well aware of the infection by now, and its effects were painted all over the ship. Around every corner was another corpse, its flesh mangled and half-eaten. Blood stains everywhere. The critical status of the ship, however, was still very much unknown to a large segment of passengers.

The number of wounded he passed along the way was startling. The newly infected often crowded into the hospitals or just ran around looking for anyone they thought could help them. Those further along in the cycle sat hunched over in chairs or lying on the floor, trembling and foaming at the mouth.

He tried his best to ignore those of the non-violent variety, even going out of his way to walk around them. Those that he couldn’t avoid he asked to return to their rooms. It tore at his heart to do so. Not helping people in need went squarely against his nature, but these people couldn’t be helped, not in any real sense. Becoming infected, while no fault of their own, guaranteed they wouldn’t have a seat on a lifeboat. Like him, they were already dead. They just didn’t know it yet. Soon the sea would sign their death certificate.

Those of the violent form were also quite numerous, though he didn’t try nearly as hard to avoid them. Sometimes he would even help fight them off if he saw them attacking a crowd. He didn’t have a gun or knife or any other conventional weapon, all he had were his hands and the certain knowledge that in no more than an hour or two he’d be dead. This unfortunate truth brought a level of toughness out of him that he’d never exuded before. For the first time in his life, he had no fear.

No more timid Thomas Andrews.

He strolled along the A-decks first-class open promenade tossing any chairs that weren’t nailed down off the side of the ship. Perhaps someone could use them to stay afloat later if it came to it. Above him on the boat deck, he could hear the officers beginning to load the lifeboats, along with the occasional gunshot.

As he came to the entrance to the aft first-class staircase, a dozen passengers came running out, hollering in fright at the disfigured monster behind them. Not long ago the monster had been a woman from first-class.

Читать дальше