Smith sighed, struggling to hold back his irritation. The managing director, with his boorish tone and dancing brown mustache, had a way of lighting a fuse in him like few others.

“Good evening, Mr. Ismay.”

LIGHTOLLER

10:27 p.m.

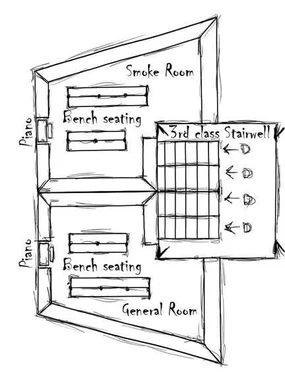

Lightoller sat at the small table outside the third-class general room, blowing into his hands to warm them. The temperature outside was thirty-two degrees, or at least it had been when his watch ended at ten. Could have gotten even colder in the last half hour, sure felt like it.

The walk across the boat deck had been slow and painful, and the thin walls enclosing the third-class stairwell did little to keep out the bone chilling air. When he thought of lookout’s Frederick Fleet and Reginald Lee sitting in the crow’s nest atop the foremast, the cold wind punishing their faces at twenty-two knots as they scanned for bergs on the dark horizon, Lightoller felt lucky to be indoors.

He had the next two hours on guard, babysitting the infected. When midnight came, he planned to be in his bed wrapped up in a blanket. Sleeping, hopefully.

He couldn’t remember the last time he’d felt so sleep deprived. If Friday night was tough, Saturday night was unbearable. It had been almost two a.m. before he made it to his room, and he had to be back up and on watch at six. Best-case scenario, sleep for three and a half hours. What he actually got was less than half that.

His mind had kept him up, even if his body was tired and his eyes felt heavy and sore. He had sat up in bed thinking about everything that happened, about all the innocent victims, about the lives he had taken and those he couldn’t save. No image haunted him more than that of the young boy he had shot in the second-class corridor.

While he didn’t regret pulling the trigger, as the boy was already dead long before the bullet hit him, Lightoller did feel regret for allowing the boy to become infected in the first place. And for the twenty or so others now quarantined within the general room. Not long ago they had dreams and aspirations, places they wanted to be, things they wanted to see. They had families that loved them, and children who needed them. Now their only desire was to spread the virus that was responsible for taking all of that away.

The virus that stole their humanity.

Lightoller slouched back in the chair, smoking his pipe and listening to the scratching and beating on the door in front of him.

That was the worst part of babysitting. The noise. It never stopped. And at times, he swore the door was swelling outward and beginning to crack under the pressure applied by the infected pushing from the other side.

He had his Webley revolver on the table in front of him, a weak defense if they managed to break through the door. He remembered what Dr. Simpson and William Dunford did to the door to the first patient room. How much longer would this door last, and how would he take down twenty infected with just six bullets?

I wouldn’t. I’d run like hell, he thought, smoke billowing from his pipe. Aye, that’s what I’d do.

As the end of the hour approached, Lightoller found it harder and harder to keep his eyes open. Sleep had decided to come and try to take him at the worst possible time. He’d begin to drift away and be jolted back awake by the hot ash burning on his lap after dumping his pipe, or by his head rocking backward and hitting against the wall—both painful eye openers.

Just as he started to drift off again, he heard soft footsteps on the stairs. A moment later, a woman who looked to be in her seventies reached the apex of the staircase and looked over at him. Clasped in her hands was a single sheet of paper.

Lightoller sat up as the woman approached the table. She looked familiar. “How may I help you?”

“Do you remember me?”

“You were here last night.”

“Yes. My name is Abigail Barnes. My husband’s name is George. Is he still in there? Can you tell me how he is doing? I came here earlier today, but the man who was here said he didn’t know.”

“I’m afraid I can’t help you either, ma’am. The last contact I had was last night when you were here.”

“Oh, dear.”

“I’m sorry.”

“I’m just so lonely now. I don’t know how to go on without him.”

“As much as I wish I could give you good news, I can’t. Everything I said last night was the truth. I don’t know what more to say.”

“I understand.” She lifted the piece of paper up and looked down at it. Her eyes held all the sorrow of a new widows. “Would it be okay if I read something to him?”

“I can’t let you inside.”

“Can I read it through the door?”

Lightoller took a deep breath, considering her request. Finally, he sighed and said, “I suppose that would be fine.”

“Thank you.”

The elderly woman named Abigail shuffled up to the door to the general room and stood there for a moment looking like she had forgotten why she’d come. She looked down at the paper and seemed to regain her focus. Lightoller figured time must have snuffed out much of her hearing, because she didn’t look bothered by the inhuman sounds coming from the other side of the door—the noise that had never once stopped until, strangely, the woman began reading from the paper.

Then silence.

Her voice was barely above a whisper, but Lightoller could hear every word.

“My loving George. The kindest man I’d ever known,” she began, her hands trembling. “Being married to you for the last fifty-three years has been the greatest gift. You took me away from an abusive father, and promised you’d take care of me. To this day, you kept your word. You were a great father to our three beautiful children. You worked so hard to keep us safe and healthy, and you never missed an opportunity to make us smile. There is so much more I would tell you, if there were words to express it. My heart is telling me our time is over, and that we had a good run. But my soul refuses to let it end here. Should you find your way to heaven, I know you’ll save a spot for me by your side. Where you go, I go. I love you, George, and I’ll see you soon.”

She lowered the paper and looked over at Lightoller. From across the room, under the dim overhead lighting, he could see the tears in her eyes. Her words made him think of his wife, Sylvia, and how much he missed her and the boys. He hoped she was at home thinking about—

The thin wood split apart with tremendous force, throwing dust and debris through the air. Before Lightoller even knew what had happened, the grey, muscular arm that smashed through the door seized Abigail and pulled her arm back through the hole, pinning her body against the door.

Lightoller rushed around the table and grabbed a hold of Abigail. The sounds coming from her mouth now weren’t beautiful or poetic. They weren’t even words. They were shrieks of intolerable agony.

He managed to pull her away from the door more easily than he expected. After she collapsed back into his arms and he saw the blood flow out of her like water from a garden hose, he understood why. In a matter of seconds, the undead creatures in the general room had chewed her arm off at the elbow.

Lightoller pulled her close to him, trying to comfort her in her last moments.

“Hold...me...George.”

There wasn’t time to explain to her that he wasn’t her husband. As the blood raced out, so did the life in her eyes. Any moment now, she’d be gone. The infected did not intend to wait, as a dozen hands began clawing at the breach in the door, ripping open a larger hole piece by piece.

Lightoller carefully placed Abigail down against the wall and hustled back to the table to get his revolver. Then he shot all six rounds through the opening in the door, realizing instantly how little it would delay their escape. The door was almost shredded. They could taste freedom. It was literally at the end of their fingertips.

Читать дальше