‘Alas, no. Not many miles from here, where a man called Wulfric claims that he is lord—’

Abbess Hilda frowned.

‘I know the man and the place. Wulfric of Frihop, whose hall lies some fifteen miles to the east. What of it, sister?’

‘We found a brother hanging from a tree at the crossroads. Wulfric claimed the monk had been executed for insulting him. Our brother wore the tonsure of our Church, my lord bishop, and Wulfric did not conceal that he came from your own house of Lindisfarne.’

Colmán bit his lip and suppressed an intake of breath.

‘It must be Brother Aelfric. He was returning from a mission to Mercia and expected to join us here any day now.’

‘But why would Aelfric insult the thane of Frihop?’ demanded Abbess Hilda.

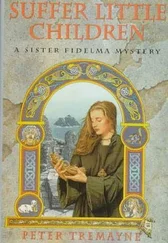

‘By your leave, Mother Abbess,’ interrupted Sister Fidelma. ‘I had the impression that this was merely an excuse. The argument was about the differences between Iona and Rome and it would seem that Wulfric and his friends favour Rome. This Brother Aelfric was apparently manoeuvred into the insult and then hanged for it.’

Hilda examined the girl sharply.

‘You do have a legal, inquiring mind, Fidelma of Kildare. But, as you well know, to hypothesise is one thing. To prove your contention is quite another.’

Sister Fidelma smiled softly.

‘I did not mean to present my impression as a legal argument, Mother Abbess. Merely that I think you would do well to have a care of Wulfric of Frihop. If he can get away with the judicial murder of a religious simply because he supports the liturgy of Colmcille then every one of us who comes to this abbey to argue in that cause may be in danger.’

‘Wulfric of Frihop is known to us. He is Alhfrith’s right hand man and Alhfrith is king of Deira,’ Hilda replied sharply. Then she sighed and shrugged and added in a softer tone, ‘And are you here to contribute to the debate, Fidelma of Kildare?’

The young religieuse gave a modest chuckle.

‘That I should dare to raise my voice among so many eloquent orators who have gathered would be an impertinence. No, Mother Abbess. I am here merely to advise on law. Our church, whose teachings your people follow, is subject to the laws of our people and the Abbess Étain, who will be speaking for our church, asked me to attend in case there is need for some advice or explanation in this matter. That is all.’

‘Then you are truly well come to this place, for your counsel is to aid us in arriving at the one great truth,’ replied Hilda. ‘And your counsel concerning Wulfric will be noted, have no fear. I shall speak concerning the matter with my cousin, King Oswy, when he arrives tomorrow. Iona or Rome, both are under the protection of the royal house of Northumbria.’

Sister Fidelma grimaced wryly. Royal protection had not helped Brother Aelfric. She decided, however, to change the subject.

‘I am forgetting one of the purposes of my disturbing you.’

She reached within her habit and brought out two packages.

‘I have journeyed here from Ireland through Dál Riada and the Holy Island of Iona.’

Abbess Hilda’s eyes grew misty.

‘You have stayed on the Holy Island where the great Columba lived and worked?’

‘Well, tell us, did you meet with the abbot?’ asked Colmán, interested.

Fidelma nodded.

‘I saw Cumméne the Fair and he sends greetings to you both and these letters.’ She held out the packages. ‘He makes a strong plea for Northumbria to adhere to the liturgy practised by Colmcille. Further, as a gift to the abbey of Streoneshalh, Cumméne Finn has sent a gift by me. I have left it with your librarius. It is a copy of Cumméne’s own book on the miraculous powers of Colmcille, of saintly name.’

Abbess Hilda took her package from Fidelma’s hand.

‘The Abbot of Iona is wise and generous. How I envy you your visit to such a sanctified place. We owe so much to that miraculous little island. I shall look forward to studying the book later. But this letter draws my attention …’

Sister Fidelma inclined her head.

‘Then I will withdraw and leave you to study the letters from Cumméne Finn.’

Colmán was already deep into his letter and scarcely looked up as she bowed her head and withdrew.

Outside, in the sandstone-flagged cloisters, Sister Fidelma paused and smiled to herself. She found herself in a curiously exhilarated mood in spite of the length of her journey and her fatigue. She had never travelled beyond the confines of Ireland before and now she had not only crossed the grey, stormy sea to Iona, but travelled through the kingdom of the Dál Riada, through the country of Rheged to the land of the Northumbrians – three different cultures and countries. There was much to take in, much to be considered.

Pressing for her immediate attention was the fact of her arrival at Streoneshalh on the eve of the highly anticipated debate between the churchmen of Rome and those of her own culture and she would not only witness it but be a part of it. Sister Fidelma was possessed of a spirit of time and place, of history and mankind’s place in its unfolding tapestry. She often reflected that, had she not studied law under the great Brehon Morann of Tara, she would have studied history. But law she had studied. Had she not, perhaps the Abbess Etain of Kildare would not have invited her to join her delegation, which had left for Lindisfarne at the invitation of Bishop Colman.

The summons had come to Fidelma while she had been on a pilgrimage to Armagh. In fact, Fidelma had been surprised at it, for when she had left her own house of Kildare Étain had not been abbess. She had known Étain for many years and knew her reputation as a scholar and orator. Étain, in retrospect, had been the correct choice to take the office of abbess on the death of her predecessor. The word had come to Fidelma that Étain had already left for the kingdom of the Saxons and so Fidelma had decided to proceed firstly to the monastery of Bangor and then cross the stormy strait to Dál Riada. Then from Iona she had joined Brother Taran and his companions, who had been setting out on a mission to Northumbria.

There had been only one other female in the band and that had been Brother Taran’s fellow Pict, Sister Gwid. She was a large raw-boned girl, giving an impression of clumsy awkwardness, her hands and feet seemingly too large. Yet she seemed always anxious to please and did not mind doing any work of drudgery no matter how heavy the task. Fidelma had been astonished to find that Sister Gwid, after her conversion to Christ, had studied at Iona before crossing to spend a year in Ireland, studying at the abbey of Emly during the time when Étain had been a simple instructress there. Fidelma was more than surprised to find that Gwid had specialized in Greek and a study of the meaning of the writings of the apostles.

Sister Gwid confided to Fidelma that she had been on her return journey to Iona when she, too, had been sent a message from the Abbess Étain to join her in Northumbria to act as her secretary during the debate that was to take place. No one objected, therefore, to Gwid and Fidelma joining the party led by Taran on the hazardous journey south from Iona to the kingdom of Oswy.

The journey with Brother Taran had simply confirmed Fidelma’s dislike of the Pictish religieux. He was a vain man, darkly handsome according to some notions, but with looks which made Fidelma regard him as a pompous bantam cock, strutting and preening. Yet, as a man with knowledge of the ways of the Angles and Saxons, she would not argue with his ability in easing their path through the hostile land. But as a man she found him weak and vacillating, one minute attempting to impress, another hopelessly inadequate – as at their confrontation with Wulfric.

Читать дальше