Eyal, Nir - Hooked - How to Build Habit-Forming Products

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Eyal, Nir - Hooked - How to Build Habit-Forming Products» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2014, Издательство: Nir Eyal, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products

- Автор:

- Издательство:Nir Eyal

- Жанр:

- Год:2014

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

- Non-routine (too new)

- Brainstorm three testable ways to make the intended tasks easier to complete.

- Consider how you might apply heuristics to make habit-forming actions more likely.

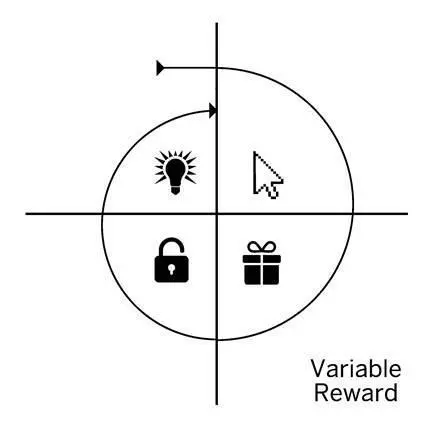

4. VARIABLE REWARD

Ultimately, all businesses help users achieve an objective. As we learned in the previous chapter, reducing the steps needed to complete the intended outcome increases the likelihood of that outcome. But to keep users engaged, products need to deliver on their promises. To form the learned associations we discussed in the chapter on triggers, users must come to depend on the product as a reliable solution to their problem — the salve for the itch they came to scratch.

The third step in the Hook Model is the Variable Reward phase. In this phase, you reward your users by solving a problem, reinforcing their motivation for the action taken in the previous phase. But to understand why rewards — and variable rewards in particular — are so powerful, we must first take a trip deep inside the brain.

Understanding Rewards

In the 1940s, two researchers named James Olds and Peter Milner accidentally discovered how a special area of the brain is the source of our cravings. The researchers implanted electrodes in the brains of lab mice that enabled the mice to give themselves tiny electric shocks to a small area of the brain called the nucleus accumbens. [lxix]The mice quickly became hooked on the sensation.

Olds and Milner demonstrated that the lab mice would forgo food, water, and even run across a painful electrified grid for the opportunity to continue pressing the lever that administered the shocks. A few years later, other researchers tested the human response to self-administered stimulus in the same area of the brain. The results were just as dramatic as in the mouse trial — subjects wanted to do nothing but press the brain-stimulating button. Even when the machine was turned off, people continued pressing the button. Researchers even had to forcibly take the devices from subjects who refused to relinquish them.

Given the responses they had earlier demonstrated from lab animals, Olds and Milner concluded that they had discovered the brain’s pleasure center. In fact, we now know other things that feel good also activate the same neural region. Sex, delicious food, a bargain, and even our digital devices all tap into this deep recess of the brain, providing the impetus for many of our behaviors.

However, more recent research has shown that Olds and Milner’s experiments were not stimulating pleasure per se. Stanford Professor Brian Knutson, conducted a study exploring blood flow in the brains of people wagering while inside of an fMRI machine. [lxx]The test subjects played a gambling game while Knutson and his team looked at which areas of their brains became more active. The startling results showed that the nucleus accumbens was not activating when the reward (in this case a monetary payout) was received, but rather, in anticipation of it.

The study revealed that what draws us to act is not the sensation we receive from the reward itself, but the need to alleviate the craving for that reward. The stress of desire in the brain appears to compel us, just as it did in Olds’ and Milner’s lab mouse experiments.

Understanding Variability

If you’ve never watched a YouTube video of a baby’s first encounter with a dog, it’s worth doing. Not only are these videos incredibly cute, but they help demonstrate something important about our mental wiring.

At first, the expression on the baby’s face seems to ask, “What is this hairy monster doing in my house? Will it hurt me? What will it do next?” The child is filled with curiosity, uncertain if this creature might cause harm. But soon the child figures out Rover is not a threat. What follows is an explosion of infectious giggles. Researchers believe laughter may in fact be a release valve when we experience the discomfort and excitement of uncertainty, but without fear of harm. [lxxi]

What we do not see in the videos is what happens over time. A few years later, what was once thrilling about Rover, no longer holds the child’s attention in the same way. The child has learned to predict the dog’s behavior and no longer finds the pup quite as entertaining. By now, the child’s mind is occupied with dump trucks, fire engines, bicycles, and new toys that stimulate the senses — until they too become predictable. Without variability, we are like children in that once we figure out what will happen next, we become less excited by the experience. The same rules that apply to puppies also apply to products. To hold our attention, products must have an ongoing degree of novelty.

Our brains have evolved over millennia to help us figure out how things work. Once we understand causal relationships, we retain that information in memory. Our habits are simply the brain's ability to quickly retrieve the appropriate behavioral response to a routine or process we have already learned. Habits help us conserve our attention for other things while we go about the tasks we perform with little or no conscious thought.

However, when something breaks the cause-and-effect pattern we've come to expect — when we encounter something outside the norm — we suddenly become aware of it again. [lxxii]Novelty sparks our interest, makes us pay attention, and — like a baby encountering a friendly dog for the first time — we seem to love it.

Rewards of the Tribe, Hunt, and Self

In the 1950s, psychologist B.F. Skinner conducted experiments to understand how variability impacted animal behavior. [lxxiii]First, Skinner placed pigeons inside a box rigged to deliver a food pellet to the birds every time they pressed a lever. Similar to Olds’ and Milner’s lab mice, the pigeons learned the cause-and-effect relationship between pressing the lever and receiving the food.

In the next part of the experiment, Skinner added variability. Instead of providing a pellet every time a pigeon tapped the lever, the machine discharged food after a random number of taps. Sometimes the lever would dispense food, sometimes not. Skinner revealed that the intermittent reward dramatically increased the number of times the pigeons tapped the lever. Adding variability increased the frequency of the pigeons completing the intended action.

Skinner’s pigeons tell us a great deal about what helps drive our own behaviors. More recent experiments reveal that variability increases activity in the nucleus accumbens and spikes levels of the neurotransmitter dopamine, driving our hungry search for rewards. [lxxiv]Researchers observed increased dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens in experiments involving monetary rewards as well as in a study of heterosexual men viewing images of attractive women’s faces. [lxxv]

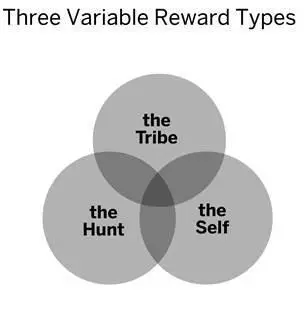

Variable rewards can be found in all sorts of products and experiences that hold our attention. They fuel our drive to check email, browse the web, or bargain-shop. I propose that variable rewards come in three types: Tribe, hunt and self (figure 20). Habit-forming products utilize one or more of these variable reward types.

Figure 20

Rewards of the Tribe

We are a species that depends on each other. Rewards of the tribe, or social rewards, are driven by our connectedness with other people. Our brains are adapted to seek rewards that make us feel accepted, attractive, important, and included. Many of our institutions and industries are built around this need for social reinforcement. From civic and religious groups to spectator sports and “watercooler” television shows, the need to feel social connectedness shapes our values and drives much of how we spend our time.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.