Eyal, Nir - Hooked - How to Build Habit-Forming Products

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Eyal, Nir - Hooked - How to Build Habit-Forming Products» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2014, Издательство: Nir Eyal, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products

- Автор:

- Издательство:Nir Eyal

- Жанр:

- Год:2014

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Sometimes the psychological motivator is not as obvious as those used by Obama supporters or fast food chains. The Budweiser ad in figure 5 illustrates how the beer company uses the motivator of social cohesion by displaying three “buds,” cheering for their national team. Although beer is not directly related to social acceptance, the ad reinforces the association that the brand goes together with good friends and good times.

Figure 5

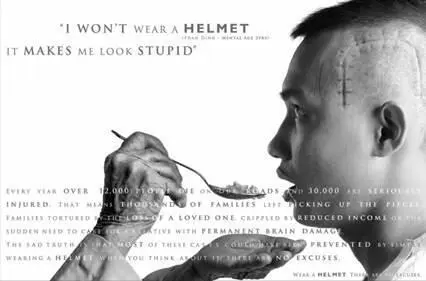

On the flip-side, negative emotions such as fear can also be powerful motivators. The ad in figure 6 shows a disabled man with a shocking head scar. The ad is impactful, communicating the risks of not wearing a motorcycle helmet. The words, "I won't wear a helmet it makes me look stupid," along with the patient’s mental age (post-motorcycle accident) of two-years old, send a chilling message.

Figure 6

As described in the previous chapter on triggers, understanding why the user needs your product or service is critical. While internal triggers are the frequent itch experienced by users throughout their days, the right motivators create action by offering the promise of desirable outcomes (i.e., a satisfying scratch).

However, even with the right trigger enabled and motivation running high, product designers often find users still don’t behave the way they want them to. What’s missing in this equation? Usability, or rather, the ability of the user to take action easily.

Ability

In his book, Something Really New: Three Simple Steps to Creating Truly Innovative Products [lviii] , author Denis J. Hauptly deconstructs the process of innovation into its most fundamental steps. First, Hauptly says, understand the reason people use a product or service. Next, lay out the steps the customer must take to get the job done. Finally, once the series of tasks from intention to outcome is understood, simply start removing steps until you reach the simplest possible process.

Consequently, any technology or product that significantly reduces the steps to complete a task will enjoy high adoption rates by the people it assists. For Hauptly, easier equals better.

But can the nature of innovation be explained so succinctly? Perhaps a brief detour into the technology of the recent past will illustrate the point.

A few decades ago, a dial-up Internet connection seemed magical. All users had to do was boot-up their computers, hit a few keys on their desktop keyboards, wait for their modems to screech and scream as they established connections, and then, perhaps 30 seconds to a minute later, they were online. Checking email or browsing the nascent World Wide Web was terribly slow (by today’s standards), but offered unprecedented convenience compared to finding information any other way. The technology was remarkable and soon became a ritual for millions of people accessing this new marvel known as the Internet.

Of course, today few of us could stand the torture of using a 2400 baud modem after we’ve become accustomed to our always-on, high-speed Internet connections. Emails are now instantaneously pushed to the devices in our pockets. Our photos, music, videos, and files — not to mention the vastness of the open web — are accessible almost anywhere, anytime, on any connected device.

In line with Hauptly’s assertion, as the steps required to get something done (in this case, to get online and use the Internet) were removed or improved upon, adoption increased.

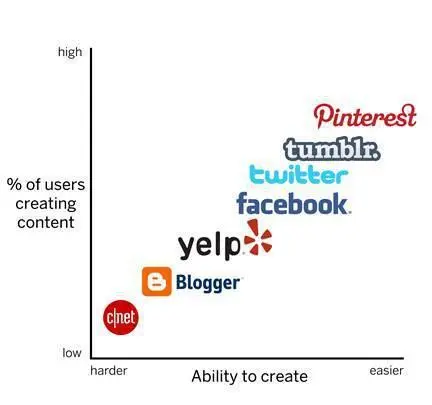

For example, consider the trend-line of the relationship between the percentage of people creating content online and the increasing ease of doing so, as shown in figure 7.

Figure 7

Web 1.0 was categorized by a few content providers like C|net (now called CNET) or the New York Times publishing to the masses, with only a tiny number of people creating what others read.

But in the late 1990s, blogging changed the web. Before blogging, amateur writers had to purchase their own domain, fiddle with DNS settings, find a web host, and set up a content-management system to present their writing. Suddenly, new companies like Blogger eliminated most of these steps by allowing users to simply register an account and start posting.

Evan Williams, who co-founded Blogger and later Twitter, echoes Hauptly’s formula for innovation when he describes his own approach to building two massively successful companies. [lix]“Take a human desire, preferably one that has been around for a really long time… Identify that desire and use modern technology to take out steps.” Blogger made posting content online dramatically easier. The result? The percentage of users creating content online, as opposed to simply consuming it, increased.

Along came Facebook and other social media tools, refining earlier innovations such as Bulletin Board Systems (BBS) and Really Simple Syndication (RSS) feeds into tools for status update-hungry users.

Then, seven years after Blogger’s birth, a new company described at first as a “micro-blogging” service sought to bring sharing to the masses — Twitter. For many, blogging was still too difficult and time-consuming. But anyone could type short, casual messages. “Tweeting” began to enter the national lexicon as Twitter gained wider adoption, climbing to 500 million registered users by 2012. [lx]Critics first discounted Twitter’s 140-character message limitation as gimmicky and restrictive. But little did they realize the constraint actually increased users’ ability to create. A few keyboard taps and users were sharing. As of late 2013, 340 million tweets were sent every day.

More recently, companies such as Pinterest, Instagram and Vine have elevated online content creation to a new level of simplicity. Now, just a quick snap of a photo or re-pin of an interesting image shares information across multiple social networks. The pattern of innovation shows that making a given action easier to accomplish spurs each successive phase of the web, helping to turn the once-niche behavior of content publishing into a mainstream habit.

As recent history of the web demonstrates, the ease or difficulty of doing a particular action impacts the likelihood that a behavior will occur. To successfully simplify a product, we must remove obstacles that stand in the user’s way. According to the Fogg Behavior Model, ability is the capacity to do a particular behavior .

***

Fogg describes six “elements of simplicity” — the factors that influence a task’s difficulty. [lxi]These are:

- Time - How long it takes to complete an action.

- Money - The fiscal cost of taking an action.

- Physical Effort - The amount of labor involved in taking the action.

- Brain Cycles - The level of mental effort and focus required to take an action.

- Social Deviance - How accepted the behavior is by others.

- Non-Routine - According to Fogg, “How much the action matches or disrupts existing routines.”

To increase the likelihood of a behavior occurring, Fogg instructs designers to focus on simplicity as a function of the user's scarcest resource at that moment. In other words, identify what the user is missing. What is making it difficult for the user to accomplish the desired action?

Is the user short on time? Is the behavior too expensive? Is the user exhausted after a long day of work? Is the product too difficult to understand? Is the user in a social context where the behavior could be perceived as inappropriate? Is the behavior simply so far outside of the user’s normal routine that its strangeness is off-putting?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.