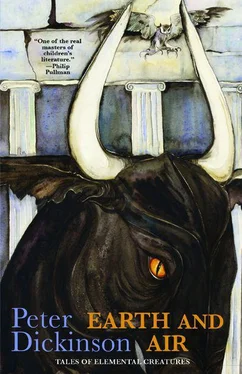

Peter Dickinson - Earth and Air

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Dickinson - Earth and Air» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: Big Mouth House, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Earth and Air

- Автор:

- Издательство:Big Mouth House

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:9781618730398

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Earth and Air: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Earth and Air»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Earth and Air — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Earth and Air», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The wizand could have swept the lawn on its own, but with her parents watching through the patio window Sophie kept firm hold of it, following its movements like a dancing partner, while it used the wind to gather the leaves into three neat piles in places where they would no longer blow around.

“It’s wonderful what a kid can do by way of work, provided she thinks she’s playing,” said her father. He was the sort of parent that hides from himself the knowledge that his relationship with his own child is not what it should be by theorising about the behaviour of children in general.

When she’d finished, Sophie went up to her room and sat cross-legged and straight-backed in the middle of the floor, with the broom across her thighs and her hands grasping the stick at either end. She waited.

“Yes?” said the wizand.

Sophie heard the toneless syllable as clearly as if it had been spoken aloud, but knew that it hadn’t come to her through her ears. She answered in the same manner, inside her head.

“I knew you were there. The moment I touched the tree. I felt you.”

“Yes.”

“What are you? A demon or something?”

“Wizand.”

Sophie accepted the unfamiliar word without query.

“Am I a witch?”

“Yes.”

“I thought so. Can we fly?”

“Yes.”

“We’d need to be invisible.”

“No.”

“But . . . Oh, you mean you can’t do that? Couldn’t I?”

“Not yet.”

“You can fly, and you can sweep. Anything else?”

“Power.”

“Oh . . .”

“Not yet.”

Sophie felt relieved. She didn’t know why.

“We’d better wait for a dark night,” she said.

Sophie chose a Friday, so that she could lie in on Saturday morning. She went to bed early and waited for her parents to come in and say goodnight. As soon as the door closed behind them she fetched her broom from the corner beside the wardrobe.

“They won’t come back,” she told it. “Let’s go.”

“Sleep,” said the wizand.

“Oh. It won’t be just dreaming again? We’re really going to do it?”

“Yes.”

Sophie climbed into bed with the broom on the duvet beside her, closed her eyes and was instantly asleep. The wizand waited until it sensed that the parents were also sleeping, then woke her by sending a trembling warm sensation into her forearm where it lay against the ash wood. She sat up, fully aware.

“Can we get through the window, or do we have to go outside?” she asked. “I’d need to turn off the burglar alarm.”

“Window.”

She pushed the sash up as far as it would go and picked up the broom again.

“Naked,” said the wizand.

“Oh, all right.”

Her parents considered Sophie a prudish child, but she unhesitatingly stripped off her nightie. As soon as she touched the broom again her body knew what to do. Both hands gripped the handle near the tip. She straddled the stick, as if it had been a hobby horse, and laid herself close along it, with the smooth wood pressing into chest and belly. A word came into her mouth that she had never before spoken. She said it aloud, and as the broom moved softly forward and upward she hooked her right ankle over her left beneath the bunched birch twigs. Together they glided cleanly through the window and into the open.

It was a chilly February night, with a heavy cloud layer releasing patches of light drizzle, but Sophie felt no cold. Indeed her body seemed to be filling with a tingling warmth, and as their speed increased the rush of the night air over her skin was a delectable coolness around that inward glow. Flying was like all the wonderful moments Sophie had ever known, but better, realer, truer. This was what she was for. Thinking about it beforehand she had imagined that the best part would be looking down from above on familiar landmarks, school and parks and churches small and strange-angled beneath her; but now, absorbed in the ecstasy of the thing itself, she barely noticed any of that until the lit streets disappeared behind her and they were flying low above darkened fields, almost skimming the hedgerow trees.

The broomstick swerved suddenly aside, and up, curving away, and then curving again and flying far more slowly.

“What?” it asked.

Sophie peered ahead and saw a skeletal structure against the glow from the motorway service station.

“Pylons,” she said. “Dad says they carry electricity around.”

The broomstick flew along the line of the wires, keeping well clear of them, then circled for height and crossed them with plenty of room to spare. Beyond them it descended and skimmed on westward, rising again to cross the motorway as it headed for the now looming hills.

It rose effortlessly to climb them, crossed the first ridge and dipped into a deep-shadowed valley. Halfway down the slope it slowed, circled over a dark patch of woodland, and settled down into a clearing among the trees. The moment Sophie’s bare feet touched earth the broom became inert. If she’d let go of it, it would have fallen to the ground.

She stood and looked around her. It was almost as dark in the clearing as it was beneath the trees, though they were mostly leafless by now. An owl was hooting a little way down the hill. Sophie had never liked the dark, even in the safety of her own bedroom, but she didn’t feel afraid.

“Can I make light?” she said.

“Hand. Up,” said the wizand.

Again her body knew what to do. She raised her right arm above her head, with the wrist bent and the fingers loosely cupped around the palm. Something flowed gently out of the ashwood into the hand that held it, up that arm, across her shoulder blades, on up her raised arm, and into the hand. A pale light glowed between her fingers, slightly cooler than the night air, something like moonlight but with a mauvish tinge, not fierce but strong enough to be reflected from tree trunks deep in the wood.

There was nothing special about the clearing. It was roughly circular, grassy, with a low mound to one side. A track ran across in front of the mound. It didn’t look as if it was used much. That was all. But the clearing spoke to her, spoke with voices that she couldn’t hear and shapes that she couldn’t see. There was a pressure around her, and a thin, high humming, not reaching her through her ears but sounding inside her head, in the same way that the wizand spoke to her. She wasn’t afraid, but she didn’t like it. She wasn’t ready.

“Let’s go home,” she said.

“Yes,” said the wizand.

On the way back the rapture of flight overcame her once more, but this time there was a small part of her that held itself back, so that she was able to think about what was happening to her. It was then that she first began to comprehend something central to her nature, when she saw that the rapture arose not directly from the flying itself, but from the ability to fly, the power. That was what the wizand had meant, when it had first spoken to her. Power.

Sophie was an intelligent and perceptive child, but hitherto, like most children, she had taken her parents for granted. They were what they were, and there was no need for her to wonder why. The coming of the wizand changed that, because of the need to conceal its existence from them. This meant that Sophie had to think about them, how to handle them, how to make sure they got enough of her to satisfy them, so that they didn’t demand anything she wasn’t prepared to give. Soon she understood them a good deal better than they did her, and realised—as they didn’t, and never would—that there was no way in which she and they could ever be fully at ease with each other. It wasn’t lack of love on their part, or at least what they thought of as love, but it was the wrong sort of love, too involved, to eager to share in all that happened to her, to rejoice in her happinesses and grieve for her miseries. It was, she saw, a way of owning her. She could not allow that.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Earth and Air»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Earth and Air» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Earth and Air» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.