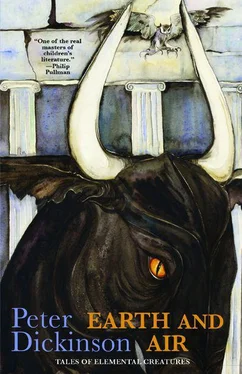

Peter Dickinson - Earth and Air

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Dickinson - Earth and Air» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: Big Mouth House, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Earth and Air

- Автор:

- Издательство:Big Mouth House

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:9781618730398

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Earth and Air: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Earth and Air»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Earth and Air — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Earth and Air», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Wizands, of course, were always scarce and local, and modern forestry methods—the reduction of woodland, the decline of coppicing, and the introduction of machinery to grub out the roots of felled trees—have reduced their numbers to a point where there are probably not more than half a dozen of them left in the whole of Europe, and because of the very different life expectancy of the two hosts only one or two of these is likely to be in the active phase at any particular time.

Phase A

One afternoon, late in October l679, Phyllida Blackett sat by her hearth. Her kettle hissed on the hub. A log flared and flared again, though it had been two years drying in the shed. But Phyllida sat placidly stroking the cat on her lap as if this were an evening like any other.

As it began to grow dark she took the new broom she had cut and bound—ash handle and birch twigs—and propped it behind the door. She picked up her old broom, carried it out into the wood that surrounded her cottage, and slipped it into the hollow centre of an old ash tree.

“You bide there and take your rest,” she said. “And luck befall you next time. I’d see to that, did I know how.”

She was a thoughtful symbiote.

Later that night, as she had known they would—known from the hiss of the kettle, the flames spurting from the log, the grain of the cat’s fur—the Community of the Elect came up the hill and laid hands on her. While their minister chanted psalms in the belief that he was restraining her powers, they drove a stake into the ground, piled logs from her shed around it, and bound her to the stake with cords that had been nine days soaking in the holy water of their font. Before they fired the wood they searched her cottage, found the broomstick behind the door, and added it to the pile, but not, of course, within her reach.

A wizand has no ears, so the one in the old broomstick could not be said to have heard Phyllida’s screams, but it sensed them, as it sensed the yells and jeering of the Community, ringing the bonfire. But unlike the exulting mob it knew that the screams were not of agony. Phyllida had both power and knowledge. She had seen to it that she would feel no pain. She could, if she had chosen, have lived longer, either by moving to a different district or by using their joint power and knowledge, hers and the wizand’s, to defend her cottage. But she felt that the time was ripe. It was better to go cleanly like this than to have the Community eventually take her in her helpless senility. The wizand, of course, for its very different reasons, took the same view.

Still, Phyllida screamed. She could just have well have simply chanted the words that she wove into the screams, but then her jeering captors might have begun to doubt that they were in full control, and themselves fallen silent, and been afraid. Better to harness the anger and frustration and cruelty that streamed out of them as they watched her burn, to add that power to her own, to use it to bind their souls to this place after they died, to hold them back from both heaven and hell and fasten them to the sour clods and granite of this valley for three hundred years and thirty and three more.

Enormous energies were released by this final exercise of power. As they finished their work the wizand absorbed them into itself. At last, when the screams were silent, the Community trooped back down to their village in a single compact body, moving like sleepwalkers, and the wizand, sated, slipped out of the broomstick into the ash tree itself, found a place close above the bole where it was both safe and comfortable, and let itself drift into torpor.

Eighty odd years later a young and energetic man inherited the estate. He looked at the abandoned village at the foot of the hill, disliked its aspect, and gave orders for a fresh settlement to be built further down the stream. To provide an economic basis for the villagers he set about a general improvement of the land, the enclosure of fertile areas, and the exploitation of timber resources. Men came to coppice the wood.

As the first axe bit ringingly into the ash tree the wizand woke and glided down into the base of the bole, just below ground level. Next spring a ring of young shoots sprang from the still-living sapwood beneath the bark. They grew to wands, then poles. When they were an inch or so thick the wizand slid back up into one and waited again.

Seven times, at twenty-year intervals, the wood was fresh coppiced, but only for two or three years in each cycle were the saplings right for the wizand’s needs, and no possible host came near while that was so. By the time the timber was carted away it was long poles, thicker than a man’s calf, and the wizand, safe in the bole, waited without impatience for the next regrowth.

The economics of forestry changed again, and the coppicing ceased. It was another hundred and ten years before the ash tree was once more felled. This time it happened with the clamour of an engine, and hooked teeth on a chain that clawed so fast into the trunk that the wizand needed to wake almost fully from its torpor and hurry past before it was trapped above the cut. More engines dragged the timber away, and the shattered wood was left in peace. Next spring, as always, fresh shoots sprang up, ringing the severed bole.

Phase B

A man’s voice.

“These look about the right size. Which one do you want, darling?”

Another voice, petulant with boredom.

“I don’t know.”

The second voice triggered the change. Instantly the wizand was fully alert, waiting, knowing its own needs, just as a returning salmon knows the stream that spawned it. It guided the reaching arm. Through the young bark of the sapling it welcomed palm and fingers. The hand was very small, a child’s, about seven years old, but now that the wizand was properly awake it saw how time was running out. There was little chance of another possible host coming by, and none of the ash tree being coppiced again, before the appointed hour.

“This one,” said the child’s voice, firmly.

A light saw bit sweetly in. The wizand stayed above the cut.

“I’ll carry it,” said the child.

“If you like. Just don’t get it between your legs. Or mine. Now what we want next is a birch tree, and some good hemp cord. None of your nasty nylon—not for a witch’s broom.”

When the children came in from their trick-or-treating the several witches piled their brooms together. As they were leaving, a child happened to pick out the wrong one. She let go and snatched her hand back with a yelp.

“It bit me,” she said, and started to cry, more frightened than hurt.

“Of course it did,” said Sophie Winner. “That’s my broom. It won’t let anyone else touch it.”

They thought she was joking, of course, and later that evening Simon and Joanne Winner found it gratifying that Sophie was so pleased with her new broom that she took it up to bed with her, and went upstairs without any of the usual sulkings and dallyings.

Sophie dreamed that night about flying. It was a dream she’d had before, so often that she thought she’d been born with it.

The wizand was always cautious with a fresh symbiote. The revelation, when it came, was likely to be a double shock, with the discovery both of the wizand’s existence, and of the symbiote’s true self. But hitherto the girl had always been around puberty. It had never dealt with a child as young as Sophie, with her preconceptions unhardened. If anything, it was she who surprised the wizand.

A fortnight after Halloween she took her broom into the back garden, saying that she was going to sweep the leaves off the lawn.

“If you like,” said her father, laughing. “They’ll blow around a bit in this wind, but give it a go.”

He went to fetch his video camera.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Earth and Air»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Earth and Air» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Earth and Air» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.