Mark Changizi - Harnessed - How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Mark Changizi - Harnessed - How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Perseus Books Group, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man

- Автор:

- Издательство:Perseus Books Group

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

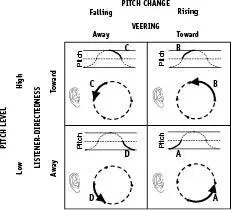

(F) High, rising pitchmeans moving toward, veering toward.

(G) High, falling pitchmeans moving toward, veering away.

(H) Low, falling pitchmeans moving away, veering away.

Figure 28. Summary of the movement meaning of pitch, for low and high pitch, and rising and falling pitch. (Note that I am not claiming people move in circles as shown in the figure. The figure is useful because all movements fall into one of these four categories, which I am illustrating via the circular case.)

These four pitch categories amount to the auditory atoms of a mover’s trajectory. Given the sequence of Doppler pitches of a mover, it is easy to decompose it into the fundamental atoms of movement the mover is engaged in. Let’s walk through these four kinds of pitch profiles, and the four respective kinds of movement they indicate, keeping our eye on Figure 28.

(A) The bottom right square in Figure 28 shows a situation where the pitch is low and rising. Low pitch means my neighborhood ice cream truck is directed away from me and the kids, but the fact that the pitch is rising means the truck is turning and directing itself more toward us. Intuitively, then, a low and rising pitch is the signature of an away-moving mover noticing you and deciding to begin to turn around and come see you. To my snack-happy children, it means hope—the ice cream truck might be coming back!

(B) The upper right square concerns cases where the pitch is higher than baseline and is rising. The high pitch means the truck is directed at least somewhat toward us, and the fact that the pitch is rising means the truck is further directing itself toward us. Intuitively, the truck has seen my kids and is homing in on them. My kids are ecstatic now, screaming, “It’s coming! It sees us!”

(C) The top left square is where the pitch is still high, but now falling. That the pitch is high means the truck is headed in our direction; but the pitch is falling, meaning it is directing itself less and less toward us. “Hurry! It’s here!” my kids cry. This is the signature of a mover arriving , because when movers arrive at your destination, they either veer away so as not to hit you, or come to a stop; in each case, it causes a lowering pitch, moving toward baseline.

(D) The bottom left, and final, square of the matrix is where the pitch is low and falling. This means the truck is now directed away, and is directing itself even farther away. Now my kids’ faces are purple and drenched with tears, and I am preparing a plate of carrots.

Figure 28 amounts to a second kind of ecological pitch-movement dictionary (in addition to Figure 26). Now, if melodic pitch contours have been culturally selected to mimic Doppler shifts, then the dictionary categorizes four fundamentally different meanings for melody . For example, when a melody begins at the bottom of the pitch range of a piece and rises, it is interpreted by your auditory system as an away-moving mover veering back toward the listener (bottom right of Figure 28). And if the melody is high in pitch and falling, it means the fictional mover is arriving (upper left of Figure 28). At least, that’s what these melodic contours mean if melody has been selected over time to mimic Doppler shifts of movers. With some grounding in the ecological meaning of pitch, we are ready to begin asking whether signatures of the Doppler effect are actually found in the contours of melody. We begin by asking how many fingers one needs to play a melody.

Only One Finger Needed

Piano recitals for six-year-olds tend to be one-finger events, each child wielding his or her favorite finger to poke out the melody of some nursery rhyme. If one didn’t know much about human music and had only been to a kiddie recital, one might suspect that this is because kids are given especially simple melodies that they can eke out with only one finger. But it is not just kindergarten-recital melodies that can be played one note at a time, but nearly all melodies. It appears to be part of the very nature of melody that it is a strictly sequential stream of pitches. That’s why, even though most instruments (including voice, for the most part) are capable of only one note at a time, they are perfectly able to play nearly any melody. And that’s also why virtually every classical theme in Barlow and Morgenstern’s Dictionary of Musical Themes has just one pitch at a time.

Counterexamples to this strong sequential tendency of melody are those pieces of music having two overlapping melodies, or one melody overlapping itself, as in a round or fugue. But such cases serve as counterexamples that prove the rule: they are not cases of a single melody relying on multiple simultaneous notes, but, rather, cases of two simultaneously played single melodies, like the sounds of two people moving in your vicinity.

Could it be that melodies are one note at a time simply because it is physically difficult to implement multiple pitches simultaneously? Not at all! Music revels in having multiple notes at a time. You’d be hard put to find music that does not liberally pour pitches on top of one another—but not for the melody.

Why is melody like this? If chords can be richly complex, having many simultaneous pitches, why can melodic contour have only one pitch at a time? There is a straightforward answer if melodic contour is about the Doppler pitch modulations due to a mover’s direction relative to the listener. A mover can only possibly be moving in a single direction at any given time, and therefore can have only a single Doppler shift relative to baseline. Melodic contour, I submit, is one pitch at a time because movers can only go in one direction at a time. In contrast, the short-time-scale pitch modulations of the chords are, I suggested earlier in the chapter, due to the pitch constituents found in the gangly bangs of human gait, which can occur at the same time. Melodic contour, I am suggesting, is the Doppler shifting of this envelope of gangly pitches.

Human Curves

Melodic contours are, in the sights of this movement theory of music, about the sequence of movement directions of a fictional mover. When the melody’s pitch changes, the music is narrating to your auditory system that the depicted mover is changing his or her direction of movement. If this really is what melody means, then melody and people should have similar turning behavior.

How quickly do people turn when moving? Get on up and let’s see. Walk around and make a turn or two. Notice that when you turn 90 degrees, you don’t usually take 10 steps to do so, and you also don’t typically turn on a dime. In order to get a better idea of how quickly people tend to change direction, I set out to find videos of people moving and changing direction. After some thought, undergraduate RPI student Eric Jordan and I eventually settled on videos of soccer players. Soccer was perfect because players commonly alter their direction of movement as the ball’s location on the field rapidly changes. Soccer players also exhibit the full range of human speeds, allowing us to check whether turning rate depends on speed. Eric measured 126 instances of approximately right-angle turns, and in each case, recorded the number of steps the player took to make the turn. Figure 29 shows the distribution for the number of steps taken. As can be seen in the figure, these soccer players typically took two steps to turn 90 degrees, and this was the case whether they were walking, jogging, or running. Casual observation of movers outside of soccer games—such as in coffee shops—suggests that this is not a result peculiar to soccer.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.