Mark Changizi - Harnessed - How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Mark Changizi - Harnessed - How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Perseus Books Group, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man

- Автор:

- Издательство:Perseus Books Group

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Figure 20. The first note is on the beat, but because it is an eighth note (lasting only half a beat), all the subsequent quarter notes (which are a beat in length) are struck on the off beat. You feel the beat occurring between each subsequent note, despite there being no note on the beat.

The beat is the solid backbone of music, so strong it makes itself felt even when not heard. And the beat is special in other ways. To illustrate this, let’s suppose you hear something strange approaching in the park. What you find unusual about the sound of the thing approaching is that each step is quickly followed by some other sound, with a long gap before the next step. Step-bang . . . . . . Step-bang . . . . . . “What on Earth is that?” you wonder. Maybe someone limping? Someone walking with a stick? Is it human at all?! The strange mover is about to emerge on the path from behind the bushes, and you look up to see. To your surprise, it is simply a lady out for a stroll. How could you not have recognized that?

You then notice that she has a lilting gait in which her forward-swinging foot strikes the ground before rising briefly once again for its proper footstep landing. She makes a hit sound immediately before her footstep, not immediately after as you had incorrectly interpreted. Step . . . . . . bang-Step . . . . . . bang-Step . . . . . . Her gait does indeed, then, have a pair of hit sounds occurring close together in time, but your brain had mistakenly judged the first of the pair of sounds to be the footstep, when in reality the second in the pair was the footstep. The first was a mere shuffle-like floor-strike during a leg stride. Once your brain got its interpretation off-kilter, the perceptual result was utterly different: lilting lady became mysterious monster.

The moral of this lilting-lady story is that to make sense of the gait sounds from a human mover, it is not enough to know the temporal pattern of gait-related hit sounds. The lilting lady and mysterious monster have the same temporal pattern, and yet they sound very different. What differs is which hits within the pattern are deemed to be the footstep sounds. Footsteps are the backbone of the gait pattern; they are the pillars holding up and giving structure to the other banging gangly sounds. If you keep the temporal pattern of body hits but shift the backbone, it means something very different about the mover’s gait (and possibly about the mover’s identity). And this meaning is reflected in our perception.

If musical rhythm is like gait, then the feel of a song’s rhythm should depend not merely on the temporal pattern of notes, but also on where the beat is within the pattern. This is, in fact, a well-known feature of music. For example, consider the pattern of notes in Figure 21.

Figure 21. An endlessly repeating rhythm of long, short, long, short, etc., but with neither “long” nor “short” indicated as being on the beat. One might have thought that such a pattern should have a unique perceptual feel. But as we will see in the following figure, the pattern’s feel depends on where the beat-backbone is placed onto it. Human gait is also like this.

One might think that such a never-ending sequence of long-short note pairs should have a single perceptual feel to it. But that same pattern sounds very different in the two cases shown in Figure 22, which differ only in whether the short or the long note marks the beat. The first of these sounds jarring and inelegant compared to the second. The first of these is, in fact, like the mysterious monster we imagined approaching a moment ago, and the second is like the lilting lady the mover turned out to be.

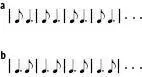

Figure 22. (a)A short-long rhythm, which sounds very different from (and less natural than) the long-short rhythm in (b).

Music, like human gait-related sounds, cannot have its beat shifted willy-nilly. The identity of a gait depends on which hits are the footsteps, and, accordingly, the identity of a song depends on which notes are on the beat. And when a beat is not heard, the brain infers its presence, something the brain also does when a mover’s footstep is inaudible.

There are, then, a variety of suspicious similarities between human gait and the properties of musical rhythm. In the upcoming section, we begin to move beyond rhythm toward melody and pitch. We’ll get there by way of discussing how chords may fit within this movement framework, and how choreography depends on more than just the rhythm.

Although we’re moving on from rhythm now, there are further lines of evidence that I have included in the Encore, which I will only provide teasers for here:

Encore 1: “The Long and Short of Hit”Earlier in this section I mentioned that the short-long rhythm of the mysterious monster sounds less natural than the long-short rhythm of the lilting lady. In this part of the Encore, I will explain why this might be the case.

Encore 2: “Measure of What?”I will discuss why changing the measure, or time signature, in music modulates our perception of music.

Encore 3: “Fancy Footwork”When people change direction while on the move, their gait often can become more complex. I show that the same thing occurs in music: when pitch changes (indicative, as we will see, of a turning mover), rhythmic complexity rises.

Encore 4: “Distant Beat”The nearer movers are, the more of their gait sounds are audible. I will discuss how this is also found in music: louder portions of music tend to have more notes per beat.

Gangly Chords

Earlier in this chapter, we discussed how footsteps and gangly bangs ring, and how these rings tend to have pitches. I hinted then that it is the Doppler shifting of these pitches that is the source of melody, something we will get to soon in this chapter. But we have yet to talk about the other principal role of pitch in music—harmony and chords.

When pitches combine in close temporal proximity, the result is a distinct kind of musical sound called the chord. For example, C, E, and G pitches combine to make the C major chord. Where do chords fit within the music-is-movement theory? To begin to see what aspect of human movement chords might echo, consider what happens when a pianist wants to get a rhythm going. He or she could just start tapping the rhythm on the wood of the piano top, but what the pianist actually does is play the rhythm via the piano keys. The rhythm is implemented with pitches. And furthermore, the pianist doesn’t just bang out the rhythm with any old pitches. Instead, the pianist picks a chord in which to establish the rhythm and beat. What the pianist is doing is analogous to what a guitarist does with a strum. Strums, whether on a guitar or a piano, are both rhythm and chord.

My suspicion is that rhythm and chords are two distinct kinds of information that come from the gangly banging sounds of human movers. I have suggested in this chapter that rhythm comes from the temporal pattern of human banging ganglies. And now I am suggesting that chords come from the combinations (or perhaps the constituents) of pitches that occur among the banging gangly rings. Gait sounds have temporal patterns and pitch patterns, and these underlie rhythm and chords, respectively. And these two auditory facets of gait are informative in different ways, but both broadly within the realm of “attitude” or “mood” or “intention,” as opposed to being informative about the direction or distance of the mover—topics that will come up later in regard to melody and loudness, respectively.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.