Mark Changizi - Harnessed - How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Mark Changizi - Harnessed - How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Perseus Books Group, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man

- Автор:

- Издательство:Perseus Books Group

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

If I am right that musical notes have their origin in the sounds that humans make when moving, then notes should come in human-gait-like patterns . In the next section, we’ll take up a simple question in this regard: does the number of notes found between the beats of music match the number of gangly bangs between footsteps?

The Length of Your Gangly

Every 17 years, cicadas emerge in droves out of the ground in Virginia, where I grew up. They climb the nearest tree, molt, and emerge looking a bit like a winged tank, big enough to fill your palm. Since they’re barely able to fly, we used to set them on our shoulders on the way to school, and they’d often not bother to fly away before we got there. And if they did fly, it wasn’t really flying at all. More of an extended hop, with an exoskeleton-shaking, tumble-prone landing. With only a few days to live, and with billions of others of their kind having emerged at the same time, all of them screeching mind-numbingly away, they didn’t need to go far to find a mate, and graceful flight did not seem to be something the females rewarded.

Cicadas have, then, a distinctively cicada-like sound when they move: a leap, a clunky clatter of wings, and a heavy landing (often with further hits and skids afterward). The closest thing to a footstep in this kind of movement is the landing thud, and thus the cicada manages to fit dozens of banging ganglies—its wings flapping—in between its landings. If cicadas were someday to develop culture and invent music that tapped into their auditory movement-recognition mechanisms, then their music might have dozens of notes between each beat. With Boooom as their beat and da as their wing-flap inter-beat note, their music might be something like “ Boooom-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-Boooom-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da,” and so on. Perhaps their ear-shattering, incessant mating call is this sound!

Whereas cicadas liberally dole out notes in between the beats, Frankenstein’s monster in the movies is a miser with his banging ganglies, walking so stiffly that his only gait sounds are his footsteps. Zombies, too, tend to be low on the scale of banging-gangly complexity (although high on their intake of basal ganglia).

When we walk, our ganglies are more complex than those of Frankenstein and his zombie dance buddies, but ours are doled out much more sparingly than the cicadas’. During a step, your leg swings forward just once, and so it can typically only get one really good bang on something. More complex behaviors can lead to more bangs per step, but most commonly, our movements have just one between-the-footsteps bang—or none. Our movements tend to sound more like the following, where “ Boooom ” is the regularly repeating footstep sound and “da” is the between-the-steps sound: “ Boooom-Boooom-Boooom-da-Boooom-Boooom-da-Boooom-da-Boooom-da-da-Boooom-da-Boooom-da-Boooom .” (Remember to do the “ Boooom ” on the beat, and cram the “ da ”s in between the beats.)

Given our human tendency to make roughly zero to one gangly bang between our steps, our human music should tend to pack notes similarly lightly between the beats. Music is thus predicted to tend to have around zero to one between-the-beats note. To test for this, we can look at the distribution of time gaps between musical notes. If music most commonly has about zero to one note between the beats—along with notes usually on the beat—then the most common note-to-note time gap should be in the range of a half beat to a beat.

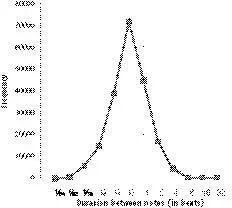

To test this, as an RPI graduate student, Sean Barnett analyzed an electronic database of Barlow and Morgenstern’s 10,000 classical themes, the ones we mentioned at the start of this chapter. For every adjacent pair of notes in the database, Sean recorded the duration between their onsets (i.e., the time from the start of the first note to the start of the second note). Figure 19 shows the distribution of note-to-note time gaps in this database—which time intervals occur most commonly, and which are more rare. The peak occurs at ½ on the x -axis, meaning that the most common time gap is a half beat in length (an eighth note). In other words, there is one note between the beats on average, which is broadly consistent with expectation.

Figure 19. The distribution of durations between notes (measured in beats), for the roughly 10,000 classical themes. One can see that the most common time gap between notes is a half beat long, meaning on average about one between-the-beat note. This is similar to human gait, typically having around zero to one between-the-step “gangly” body hit.

We see, then, that music tends to have the number of notes per beat one would expect if notes are the sounds of the ganglies of a human—not a cicada, not a Frankenzombie—mover. Musical notes are gangly hits. And the beat is that special gangly hit called the footstep. In the next section we will discuss some of what makes the beat special, and see if footsteps are similarly special (relative to other kinds of gangly hits).

Backbone

My family and I just moved into a new house. Knowing that my wife was unhappy with the carpet in the family room, and knowing how much she fancies tiled floor, I took the day off and prepared a surprise for her. I cut tile-size squares from the carpet, so that what remained was a checkerboard pattern, with hardwood floors as the black squares and carpet as the white squares.

I couldn’t sleep very well that night on the couch, and so I headed into the kitchen for a bite. As I pondered how my plan had gone so horribly wrong, I began to notice the sounds of my gait. Walking on my newly checkered floor, my heels occasionally banged loudly on hard wood, and other times landed silently on soft carpet. Although some of my between-step intervals were silent, between many of my steps was a strong bump or shuffle sound when my foot banged into the edge of the two-inch-raised carpet. The overall pattern of my sounds made it clear when my footsteps must be occurring, even when they weren’t audible.

Luckily for my wife—and even more so for me—I never actually checkered my living room carpet. But our world is itself checkered: it is filled with terrain of varying hardness, so that footstep loudness can vary considerably as a mover moves. In addition to soft terrain, another potential source of a silent step is the modulation of a mover’s step, perhaps purposely stepping lightly in order to not sprain an ankle on a crooked spot of ground, or perhaps adapting to the demands of a particular behavioral movement. Given the importance of human footstep sounds, we should expect that our auditory systems were selected to possess mechanisms capable of recognizing human gait sounds even when some footsteps are missing, and to “fill in” where the missing footsteps are, so that the footsteps are perceptually “felt” even if they are not heard.

If our auditory system can handle missed footsteps, then we should expect music—if it is “about” human movement—to tap into this ability with some frequency. Music should be able to “tell stories” of human movement in which some footsteps are inaudible, and be confident that the brain can handle it. Does music ever skip a beat? That is, does music ever not put a note on a beat?

Of course. The simplest cases occur when a sequence of notes on the beat suddenly fails to continue at the next beat. This happens, for example, in “Row, Row, Row Your Boat,” when each “row” is on the beat, and then the beat just after “stream” does not get a note. But music is happy to skip beats in more complex ways. For example, in a rhythm like that shown in Figure 20, the first beat gets a note, but all the subsequent beats do not. In spite of the fact that only the first beat gets a note, you feel the beat occurring on all the subsequent skipped beats. Or the subsequent notes may be perceived to be off-beat notes, not notes on the beat. Music skips beats and humans miss footsteps—and in each case our auditory system is able to perceptually insert the missing beat or footstep where it belongs. That’s what we expect from music if beats are footsteps.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.