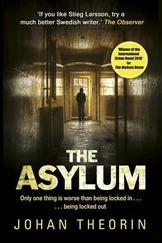

John Harwood - The Asylum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Harwood - The Asylum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, ISBN: 2013, Издательство: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Asylum

- Автор:

- Издательство:Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:9780544003293

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Asylum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Asylum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Asylum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Asylum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

His colour had risen; he was studying me as intently as politeness allowed, with every appearance of adoration. I kept my own gaze demurely fixed upon the prospect before us, wondering how he would respond if I told him we were cousins.

We were now approaching the edge of the wood. The trees were mostly oaks and alders, growing very close together; a narrow path wound its way in amongst them. Frederic began to bear away to his right.

“Shall we walk through the wood?” I asked innocently.

“Perhaps better not,” he said. “It is very overgrown, and you might . . . There is a very pleasant walk along the western side.”

He sounded natural enough, but it seemed to me that he averted his eyes from the ruin, and we walked for a little in silence, following a rough track that led us across a stretch of open field and around the end of the wood, until we were out of sight of the house.

“I remember you saying,” I ventured, “how lonely it was for you, growing up here.”

“You remember our conversation?” he exclaimed, with another heartfelt glance, which I pretended not to see. I had allowed the distance between us to diminish, so that our shoulders were almost touching. “After all you have suffered here—I am—” He seemed about to say “overwhelmed,” but checked himself.

“Yes, it was; I had no playmates, as I may have mentioned.”

“And no other relations—uncles or aunts, or cousins . . . ?”

“None living. Uncle Edmund had a younger brother, but, like my father, Horace, he took his own life.”

I stared at him in shock, caught my foot in a tussock, and grasped his arm to save myself from falling.

“I did not know,” I said. “About your father, I mean.”

“I did not like to mention it. He had been closely confined, for his own safety, but somehow . . .”

“I am truly sorry to hear it,” I said, thinking how dreadfully inadequate that sounded. Through the cloth of his jacket, I could feel his arm quivering—or was it my hand? I steeled myself to continue.

“And—the younger brother?”

“The same, I fear. He—my uncle Felix—was lost overboard, on a voyage to South America, but given the family tendency, there can be very little doubt. I came upon the report of it quite recently, when I was sorting through some papers. The ship—the Utopia, she was called—was just three days out from Liverpool. He had dined as usual that evening—the weather was calm, with only a light swell running—and that was the last anyone ever saw of him.”

“And—do you remember him at all?”

“No, he died before I was three years old; in the summer of 1860, I believe it was. I know almost nothing about him. The subject is distressing to Uncle Edmund; he prefers not to speak of it.”

I found that I was still gripping his arm, and hastily released it. Felix had not stayed with Clarissa; he had boarded the ship on which he had planned to sail with Rosina, and drowned himself, surely out of despair at losing her. He would never have made another will in Edmund’s favor; not when Edmund had been the agent of his ruin.

“Miss Ashton?—I fear I have distressed you.”

“No, no, it is only—” I took a step forward, and realised I was quite unsteady on my feet. “I should like to sit down for a little.”

I made my way over to a fallen tree, anxiously attended by Frederic, and sat down on the trunk. A few paces to my left, a path led back into the wood; I saw Frederic glance over his shoulder, and wondered if it went to the ruined stable.

“You must understand,” he said, “that, bleak as it must sound, these sad histories are part of the furniture of my mind. They have lost their power to hurt.”

A brief silence followed.

“Miss Ashton,” he said hesitantly, “what you said to me, before, has lifted a great weight from my mind. I hope you will not take it amiss if I remind you that, when you leave here, my purse will be at your disposal.”

In fact, sir, I imagined myself replying, it is my purse, and I have documents to prove it. But only if I could prove that I was Georgina Ferrars.

“You are very kind, Mr. Mordaunt,” I murmured, hoping I was not overplaying my part. “I should have been more gracious when you first made the offer.”

He gave me another of his heartfelt looks, in which a sort of incredulous hope was dawning. No one, I thought, could counterfeit such transparent emotion, those rapid changes of colour . . . I felt a wild impulse to confide in him, to trust in his sense of honour and his evident feeling for me; but then I thought of my journal, of how I had trusted just those signs in Lucia (if only I could remember trusting her). I reminded myself, too, of how much he idolised Dr. Straker, and resolved to stick to my plan.

“You spoke, Mr. Mordaunt, of when I am released. Are you confident, then, that Dr. Straker will let me go?”

“Yes, Miss Ashton, I am—though I cannot, as you know, force his hand.”

“But why is it, may I ask, that he will not release me now? I am not a danger to myself, or anyone else; I accept that I cannot be Georgina Ferrars, and I am prepared to wait patiently for my actual memory to return: what, then, is the obstacle?”

“I am afraid there are several. He fears that if he releases you prematurely—his word, not mine—your actual memory, as you call it, may never return. And he still hopes that by combing through records of missing persons—which he spends a good deal of his time doing—he will discover who you really are, and restore you to your friends and family, assuming, of course . . .” He trailed off awkwardly.

“But do you think it fair, Mr. Mordaunt, that he should keep me here, as a certified lunatic? If I am capable of living in the world, should I not be allowed to?”

“I—speaking for myself, I agree with you. I find it impossible to think of you as a lunatic, or to imagine . . .” He shook his head, as if to clear it. “The difficulty, according to Dr. Straker, is that yours is such a rare condition—he knows of only four comparable instances, all reported from France—that he simply can’t predict how, or how soon, it will resolve. My own belief, as I said to you only yesterday, is that if you could—I hesitate to say converse with, but speak to Miss Ferrars, in a setting acceptable to you both, the spell might be broken. But Dr. Straker, as I told you yesterday, is vehemently opposed to it: he fears the shock might kill you.”

“I cannot see why, Mr. Mordaunt. I agree with you; I am convinced that it would help me. In fact—of course I have no right to ask,” I said, meeting his eyes with all the appeal I could muster, “but would you be prepared to call upon Miss Ferrars at Gresham’s Yard, and try to persuade her to see me?”

“Nothing would give me greater pleasure, Miss Ashton; but Dr. Straker would never agree.”

“But supposing he is wrong? Should you not trust your own instinct? If it helps me recover my memory, and leads to my release, will he not forgive you? And have the largeness of heart to acknowledge that you were right and he was wrong? I should be eternally grateful,” I added, with another beseeching look.

“Miss Ashton, I only wish . . . The thing is, even if I were to defy him, Miss Ferrars has said that she won’t agree to it unless we can return her writing case.”

“But, as you said yourself, Mr. Mordaunt, if it helps me to remember what I did with it . . .”

He was plainly torn; his hands, clasped in his lap, were trembling.

“Something has just come to me,” I said, playing my last card. “About that writing case.”

“Yes, Miss Ashton?”

“‘Aunt Rosina’s will’: I don’t know what it means—the words just came into my head, but my heart insists that Miss Ferrars will understand them.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Asylum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Asylum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Asylum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![John Bruce - The Lettsomian Lectures on Diseases and Disorders of the Heart and Arteries in Middle and Advanced Life [1900-1901]](/books/749387/john-bruce-the-lettsomian-lectures-on-diseases-and-disorders-of-the-heart-and-arteries-in-middle-and-advanced-life-1900-1901-thumb.webp)